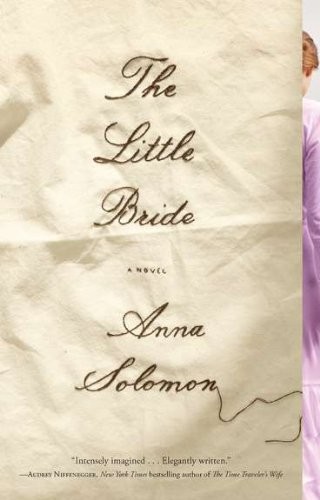

The Little Bride

Table of Contents

RIVERHEAD BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario M4P 2Y3, Canada

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd., 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Group Ireland, 25 St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd.)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty. Ltd.)

Penguin Books India Pvt. Ltd., 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi—110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd.)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty.) Ltd., 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd., Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any contol over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

RIVERHEAD is a registered trademark of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

The RIVERHEAD logo is a trademark of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

First Riverhead trade paperback edition: September 2011

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Solomon, Anna.

The little bride / Anna Solomon.

p. cm.

ISBN : 978-1-101-54423-5

1. Jewish girls–Fiction. 2. Mail order brides–Fiction. 3. Jews—South Dakota–Fiction. I. Title.

PS3619.O4329L57 2011

813’.6–dc22

2010054194

For my parents

V’ka’asher ovadeti ovadeti.

And if I perish, I perish.

or . . .

Since we are lost already,

we might just as well defend ourselves.

we might just as well defend ourselves.

Look

ONE

ODESSA, 188-

T

HE physical inspection was first. Eyes. Nose. On her chin, a thumb opened her jaw. The woman’s hands weren’t soft but they were dry, at least, like salted fish. Minna closed her eyes, then worried she looked afraid and opened them. The fingers tugged at her earlobes. They prowled at her nape.

HE physical inspection was first. Eyes. Nose. On her chin, a thumb opened her jaw. The woman’s hands weren’t soft but they were dry, at least, like salted fish. Minna closed her eyes, then worried she looked afraid and opened them. The fingers tugged at her earlobes. They prowled at her nape.

All this, she decided, was normal enough. She had been to doctors, twice, men who accepted milk for their services. The first time, she was six, and still living with her father—the milk came from his goat—and she was still a boy then, in her mind, and did not mind undressing, or standing in the cold, and was not ashamed of her unwitting body: the foot kicking out, the throat gagging. Then she was thirteen, and already in Odessa, and she had seen her breasts in Galina’s dressing-room mirror, sideways and from the front, and she carried the milk—stolen from the dairy boy’s cart—with disgrace, made worse by the reason she went: a smell of beer, a heat, a terrible itching. She was sure something in her own touching had damaged her inside, and as she walked she took a long looping detour: out Suvorovskaya, past the hospitals, through the cemeteries. She decided to say a man had done it to her, whatever “it” was—to have hurt herself seemed worse than to have been hurt by someone else. But as it turned out, the doctor asked nothing. He didn’t even make her lie on his table. He looked at her tongue, that was all. Then he gave her back the milk, telling her to let it sour into yogurt and smear it on herself at night.

But now the woman ordered Minna to take everything off, and when Minna had stripped down to her underclothes, she ordered her to take these off, too. Minna felt dizzy. The room was unheated, in a basement, in a municipal building, after hours. The only color came from orange patches of rust on the walls.

The door opened. A man entered the room, followed by another woman, followed by a tall metal contraption she rolled behind her. She held a flame to it; gas flared; white light flooded the room. Minna’s skin went taut. The lamp was the sort they brought to the mines after an accident, the sort they’d used when they pulled her father out. Its cold glare missed nothing. The stone floor was crumbling.

“Off,” the woman said again.

The man waited, a pipe in his mouth. His beard was red and tattered, as if it housed moths. Maybe he was a real doctor. Maybe he wasn’t. Minna chose to concentrate on his thin shoulders under his thin shirt, on how he kept his eyes on his fingernails, which he appeared to be cleaning with his thumbnails. He could almost look—if she looked right—apologetic.

She unknotted her bodice and folded it in half. She folded it again, then again, then set it on top of her other clothing, on the floor. Order, she thought, willing her arms not to shake. Show them order. A wife is meant to create order.

“Get on with it,” said the woman. “Drawers.”

Minna concentrated on her feet. Her toes were purple; her soles stung. She would have to sneak out to Galina’s vodka late tonight and siphon off spoonfuls for the cuts. She wouldn’t dare pump any water. The pump made a noise like a cat in heat.

“Might as well know. Hard of hearing’s a mark against you.”

The woman’s breath was close, and sharp, like seawater crossed with wine. Minna fended off her desire to pull away. She would never, she told herself, have to smell this smell again. She would live across oceans, she would have a husband, she would have her own house. Her own sink and bath, made of zinc or copper—even stone would do—in which she could wash whatever and whenever she pleased.

She slipped her drawers off her hips. She planned to catch them but her body stayed stiff: the idea of bending over now was unbearable. The man’s pipe nodded as the white cloth fell to her ankles and now her eyes closed, she couldn’t stop them; between her legs, the hairs stood. The lamp gave no heat. She concentrated on the worms of light across her eyelids, on seeing sunlight, sky. In the house, above the zinc or copper sink, would be a window, which she would dress with a lace curtain. The days would sift through the lace as a silent, dustless light.

Her eyes startled open when the fish hands cupped her breasts and lifted. At her stomach she felt a tickle: the man’s beard. He drew so close he might have been sniffing her.

“You’re sixteen?” he asked her navel.

Minna nodded.

“Your event comes every month, yes?”

She nodded again. Though sometimes she bled for a whole month straight, and sometimes not once in a year.

The tickle withdrew. “Arms,” said the man as he sucked on his pipe, and as the smoke from his exhalation swam up Minna’s front, smelling of her father, she couldn’t help but breathe it in. The woman told her, “Lift,” and started slipping her fingers around in Minna’s underarms, pressing, kneading, turning sweat to ice. At last they stopped. Slipped away. The woman nodded.

“Unremarkable,” said the man.

The woman who’d brought in the lamp scratched something in a large book.

“Fat,” declared the doctor, and the fish woman’s hands began to squeeze at Minna’s waist. The doctor circled her, observing. He was thin in the way of cellar insects, as if made to slip through cracks. Minna tried to blur her eyes. She focused instead on the pattern emerging: he questioned her, yes, but he did not command her, and he did not touch. There was a woman to perform these functions, and another to take notes. It was all part of a procedure, Minna reminded herself, a system. Rosenfeld’s Bridal Service. An underground operation, yes—but the doctor, the women, they were all Jewish. Her jaw clenched as the hands grabbed her hips, but she did not squirm. It was a service, a system, run by Jews for Jews. There was nothing personal here. Nothing to squirm from. Every bride was given her Look. Usually by the groom’s family, admittedly—but so many families had already left. Perhaps it was better this way. She’d never have to see these people again. There was a method; there were rules; there was a prize.

Other books

Lord Somerton's Heir by Alison Stuart

BELLA MAFIA by Lynda La Plante

MemoriesofParadise by Tianna Xander

Surrender of Trust (First Volume of the Surrender Series) by Mariel Grey

Where Love Shines by Donna Fletcher Crow

Road Dogs (2009)( ) by Leonard, Elmore - Jack Foley 02

Summer of Supernovas by Darcy Woods

WEAK Part Three: A Thornhill Road Romance by Drew Sinclair

Make Me Tremble by Beth Kery

Night Watcher by Chris Longmuir