The Little Ice Age: How Climate Made History 1300-1850 (9 page)

Read The Little Ice Age: How Climate Made History 1300-1850 Online

Authors: Brian Fagan

The hunger was made worse by the previous century's population

growth. Late eleventh-century England's population of about 1.4 million

had risen to 5 million by 1300. France's inhabitants (that is, that part of

Europe now lying within the country's modern boundaries) increased

from about 6.2 million in the late eleventh century to about 17.6 million

or even higher. By 1300, with the help of cereal cultivation at unprecedented altitudes and latitudes, Norway supported half a million people.

Yet economic growth had not kept pace with population. There was

already some sluggishness in local economies by 1250, and very slow

growth everywhere after 1285. With growing rural and urban populations, high transportation costs, and very limited communication networks, the gap between production and demand was gradually widening

throughout northern Europe. Many towns and cities, especially those

away from the coast or major waterways, were very vulnerable to food

shortages.

In the countryside, many rural communities survived at near-subsistence levels, with only enough grain to get through one bad harvest and

plant for the next year. Even in good years, small farmers endured the

constant specter of winter famine. All it took was a breakdown in supply

lines caused by iced-in shipping, bridges damaged by floods, an epidemic

of cattle disease that decimated breeding stock and draught animals, or

too much or too little rainfall, and people went hungry.

Even in the best of times, rural life was unrelentingly harsh. Six

decades earlier, in 1245, a Winchester farm worker who survived childhood diseases had an average life expectancy of twenty-four years. Excavations in medieval cemeteries paint a horrifying picture of health problems resulting from brutal work regimes. Spinal deformations from the

hard labor of plowing, hefting heavy grain bags, and scything the harvest

are commonplace. Arthritis affected nearly all adults. Most adult fisherfolk suffered agonizing osteoarthritis of the spine from years of heavy

boatwork and hard work ashore. The working routines of fourteenthcentury villagers revolved around the never-changing rhythm of the seasons, of planting and harvest. The heat and long dry spells of summer were a constant struggle against weeds that threatened to choke off the

growing crops. The frantically busy weeks of harvest time saw villagers

bent to the scythe and sickle and teams of threshers winnowing the precious grain. The endless round of medieval household and village never

ceased, and the human cost in constant, slow-moving toil was enormous. Yet despite the unending work, village diets were never quite adequate, and malnutrition was commonplace. Local food shortages were a

reality of life, assuaged by reliance on relatives and manorial lords or on

the charity of religious houses. Most farmers lived from harvest to harvest on crop yields that at the best of times were far below modern levels.

Both archaeology and historical records provide portraits of medieval

village life, but few are as complete as that from Wharram Percy, a deserted village in northeast England. Forty years of research have revealed a

long-established settlement that mirrors many villages of the day. Iron

Age farmers lived at Wharram Percy more than 2,000 years ago. At least

five Roman farms flourished here. By the sixth century, Saxon families

dwelt in their place. Scattered farming settlements gave way to a more

compact village between the ninth and twelfth centuries, which was replanned at least twice. The Medieval Warm Period was good to Wharram

Percy, when the settlement entered its heyday. The population grew considerably, the hectarage under cultivation expanded dramatically. The

compact village became a large settlement with its own church, two

manor houses and three rows of peasant houses, each with its own croft

(enclosure) built around a central, wedge-shaped green. The peasants

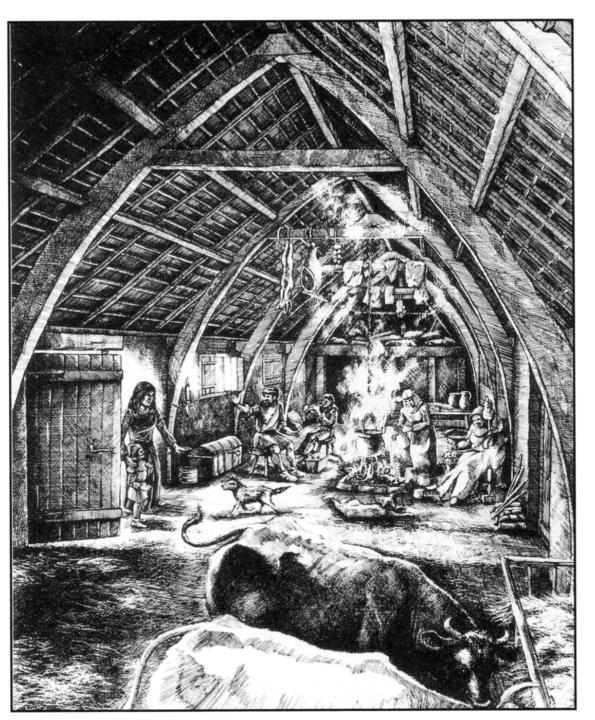

lived in thatched long houses, their roofs supported by pairs of timbers

known as crucks, with flimsy walls that were replaced at regular intervals.

Each building had three parts: an inner room for sleeping, sometimes

used as a dairy, a main living area with central hearth, and a third space

used as a cattle byte, or for some other farming purpose. (Long houses

were common in Medieval villages everywhere, although architecture and

village layout varied greatly between Scandinavia and the Alps.) Wharram

Percy was largely self-sufficient, a prosperous community in its heyday.

But the bountiful days of the thirteenth century were long fled from

memory when the village was finally abandoned in the sixteenth century.

The self-sufficiency of European villages extends deep into the past, to

long before the Romans imposed the Pax Romana on Gaul and Britannia just before the time of Christ. A millennium later, life still revolved around

the manor house and the farm, the monastery and small market towns.

Tens of thousands of parish churches formed a network of territorial authority at the village level, where, for all the political changes and land

ownership controversies, the parish priest remained a figure of respect. But

times were changing as new commercial and political interests emerged.

By 1250, a tapestry of growing cities and towns linked by tracks, water ways and trade routes lay superimposed on the rural landscape. Walled

castles and cities rose at strategic locations, creating oases of safety in troubled lands where barons fought with barons at the slightest provocation.

Towns and cities, a few with as many as 50,000 inhabitants, were places

somewhat apart, striving for their own social and political identity, peopled by a growing class of merchants and burghers, who were outside the

feudal system. Many of these towns lay at key ports and estuaries, at important river crossings, or around the residences of important lords and

bishops. But poor communications, especially on land, meant that most

communities were largely self-sufficient, as they had always been. The

parish always remained the cornerstone of the ordered life of the countryside through famine, plague, and war, long after nation states and powerful commercial associations transformed the European economy.

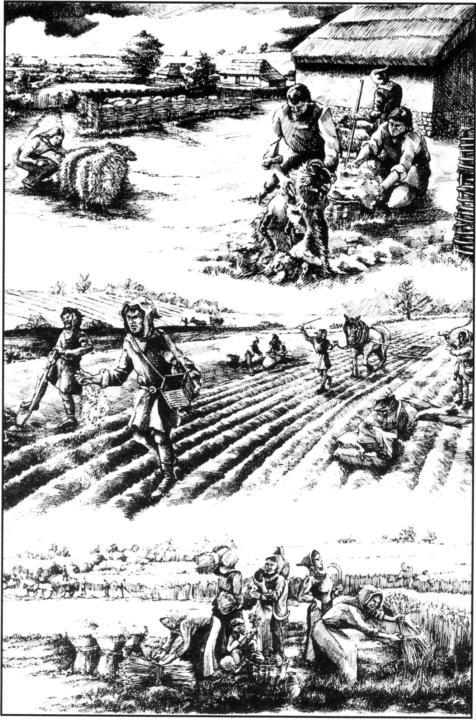

Medieval farming: sheep shearing sowing, and the harvest. Reconstruction based

on Wharram Percy, England. Reprinted with permission of English Heritage.

Medieval farming: interior of a long house with its crucks (timber beams). Reconstruction based on Wharram Percy, England. Reprinted with permission of English

Heritage.

Europe's commerce was still based on trade routes well known to the

Romans. Wool flowed across the North Sea and English Channel,

Mediterranean goods up major waterways like the Rhine and overland,

along routes between Lombardy, Genoa, and Venice, important centers

of trade with eastern Mediterranean lands. The Hanseatic League, a powerful commercial association based in Scandinavia, Germany, and the

Low Countries, was still in its infancy. Europe's rudimentary infrastructure still depended on slow, unreliable communications across potentially

stormy seas, on rivers and inland waterways, and the most rudimentary

rural tracks. The amount of grain imported from the Baltic and Mediterranean lands was still minuscule compared with later centuries. In the final analysis, every community, every town, was on its own.

Medieval farmers had few options for dealing with rainfall and cold.

They could diversify their crops, planting some drought-resistant strains

and others that thrived in wetter conditions. As a precaution, they could

sow their crops on a mosaic of different soils, hoping for better yields

from some of them. In earlier centuries they could perhaps move to richer

areas, but by 1300 most of Europe's best farmland was occupied. Storage

was all important. Enough grain had to be kept on hand to tide the community over from one harvest to the next and beyond, and to even out

the good and bad years. Even with barns stuffed to the eaves, however,

few medieval villages could endure two bad harvests, even if wealthy lords

or religious foundations with their large granaries had such a capacity.

The villagers' best recourse was the ability to exchange grain and other vi tal commodities with relatives and neighbors living close or afar. This

form of famine relief could be highly effective on a small scale, but not

when an entire continent suffered the same disaster.

Most close-knit farming communities endured the shortages of 1315 and

hoped for a better harvest the following year. Then the spring rains in

1316 prevented proper sowing of oats, barley, and spelt. The harvest

failed again and the rains continued. Complained a Salzburg chronicler

of 1316: "There was such an inundation of waters that it seemed as

though it was THE FLOOD."6 Intense gales battered Channel and North

Sea. Storm-force winds piled huge sand dunes over a flourishing port at

Kenfig near Port Talbot in south Wales, causing its abandonment. Villages throughout northern Europe paid the price for two centuries of extensive land clearance. Flocks and herds withered, crops failed, prices

rose, and people contemplated the wrath of God. The agony was slow:

famine weakens rural populations and makes them vulnerable to disease,

which follows almost inevitably in its train. The prolonged disaster is familiar from modern-day famines in Africa and India. People first turned

to relatives and neighbors, invoking the ties of kin and community that

had bound them for generations. Then many families abandoned their

land, seeking charity from relatives or aimlessly wandering the countryside in search of food and relief. Rural beggars roamed from village to village and town to town, telling (often false) stories of entire communities

abandoned or of deserted meadows and hillsides.

By the end of 1316, many peasants and laborers were reduced to

penury. Paupers ate dead bodies of diseased cattle and scavenged growing

grasses in fields. Villagers in northern France are said to have eaten cats,

dogs, and the dung of pigeons. In the English countryside, peasants lived

off foods that they would not normally consume, many of them of dubious nutritional value. They were weakened by diarrhea and dehydration,

became more susceptible to diseases of all kinds, were overcome by

lethargy, and did little work. The newborn and the aged died fastest.

Community after community despaired and slowly dissolved. Thousands of acres of farmland were abandoned due to a shortage of seed corn and draught oxen, and to falling village populations. Huge areas of the

Low Countries, inundated by the sea after major storms and prolonged

rains, were so difficult to reclaim that major landowners could hardly persuade farmers to resettle their flooded lands. Across the North Sea, in the

Bilsdale area of northeast Yorkshire, late thirteenth-century homesteaders

had cleared hundreds of acres of higher ground for new villages. A couple

of generations later, knots of hamlets, each with its own carpenters,

foresters, and tanners, flourished on the newly cleared land. But climatic

and economic deterioration, the 1316 famine, disease, and Scottish raids

caused all of them to be abandoned by the 1330s. The hamlets became

tiny single-family holdings, and the communities dispersed. Throughout

northern Europe, small farming communities on marginal land were

abandoned, or shrunk until their holdings were confined to the most fertile and least flood-prone lands.