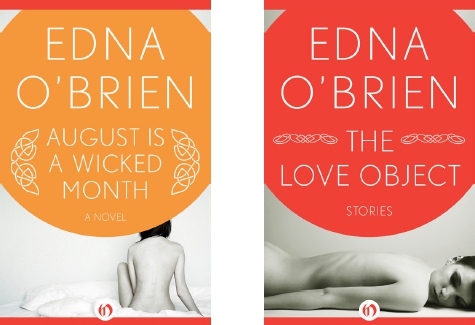

The Love Object (18 page)

Authors: Edna O'Brien

She swam in the shallow end and confronted the thought that had urged to be thought for days. She thought, I shall do it, or I shall not do it, and the fact that she was in two minds about it seemed to confirm her view of the unimportance of the whole thing. Anyone, even the youngest child, could have persuaded her not, because her mind was without conviction. It just seemed easier, that was all, easier than the strain and the incomplete loving and the excursions that lay ahead.

‘This is what I want, this is where I want to go,’ she said, restraining that part of herself that might scream. Once she went deep, and she submitted to it, the water gathered all around in a great beautiful bountiful baptism. As she went down to the cold and thrilling region she thought, They will never know, they will never, ever know, for sure.

At some point she began to fight and thresh about, and she cried though she could not know the extent of those cries.

She came to her senses on the ground at the side of the pool, all muffled up and retching. There was an agonizing pain in her chest as if the black frosts of winter had got in there. The servants were with her and two of the guests and him. The floodlights were on around the pool. She put her hands to her breast to make sure; yes she was naked under the blanket. They would have ripped her bathing suit off. He had obviously been the one to give respiration because he was breathing quickly and his sleeves were rolled up. She looked at him. He did not smile. There was the sound of music, loud, ridiculous and hearty. She remembered first the party, then, everything. The nice vagueness quit her and she looked at him with shame. She looked at all of them. What things had she shouted as they brought her back to life? What thoughts had they spoken in those crucial moments? How long did it take? Her immediate concern was they must not carry her to the house, she must not allow that last episode of indignity. But they did. As she was borne along by him and the gardener she could see the flowers and the oysters and jellied dishes and the small roast piglets all along the tables, a feast as in a dream, except that she was dreadfully clear-headed. Once alone in her room she vomited.

For two days she did not appear downstairs. He sent up a pile of books and when he visited her he always brought someone. He professed a great interest in the novels she had read and asked how the plots were. When she did come down the guests were polite and off hand and still specious, but along with that they were cautious now and deeply disapproving. Their manner told her that it had been a stupid and ghastly thing to do and had she succeeded she would have involved all of them in her stupid and ghastly mess. She wished she could go home, without any farewells. The children looked at her and from time to time laughed out loud. One boy told her that his brother had once tried to drown him in the bath. Apart from that and the inevitable letter to the gardener it was never mentioned. The gardener had been the one to hear her cry and raise the alarm. In their eyes he would be a hero.

People swam less. They made plans to leave. They had ready-made excuses – work, the change in the weather, aeroplane bookings. He told her that they would stay until all the guests had gone, and that then they would leave immediately. His secretary was travelling with them. He asked each day how she felt, but when they were alone he either read or played patience. He appeared to be calm except that his eyes blazed as with fever. They were young eyes. The blue seemed to sharpen in colour once the anger in him was resurrected. He was snappy with the servants. She knew that when they got back to London there would be separate cars waiting for them at the airport. It was only natural. The house, the warm flagstones, the shimmer of the water would accompany her and be a joy long after their love had become an echo.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook onscreen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of the publisher.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

“An Outing,” “The Rug,” “Irish Revel,” “Cords,” and “The Love Object” first appeared in the

New Yorker

, and the author and publishers are grateful for permission to include them here.

copyright © 1968 by Edna O’Brien

cover design by Angela Goddard

978-1-4532-4731-0

This edition published in 2012 by Open Road Integrated Media

180 Varick Street

New York, NY 10014

FROM OPEN ROAD MEDIA

Available wherever ebooks are sold

FIND OUT MORE AT

WWW.OPENROADMEDIA.COM

follow us:

@openroadmedia

and

Facebook.com/OpenRoadMedia

Sign up for the Open Road Media newsletter and get news delivered straight to your inbox.

FOLLOW US:

SIGN UP NOW at