The Lovers (37 page)

Authors: Rod Nordland

Mullah Mohammad Jan:

Anwar and Ali prepare for their flight to Tajikistan, buying suitcases at a marketplace in Kabul. (

Sukhanyar

)

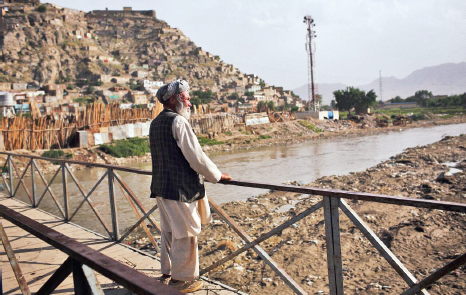

Honor Hunters:

Ali’s father, Anwar, near the Kabul River the day after his son was arrested. He had no idea where to go, and no place to stay. (

Quilty

)

A Dog with No Name:

The compound of Anwar’s house in Surkh Dar, with the new guard dog chained outside. (

Quilty

)

“We have our proof”:

Ali’s mother, Chaman; Zakia with Ruqia, age two months; and Ali, February 2015. (

Quilty

)

“She can smell her family in the air”:

Ali, in the family home in Surkh Dar, still in hiding well into 2015. (

Quilty

)

“He is still nervous when he holds her”:

Ali with his daughter, Ruqia, at his father’s house in the village of Surkh Dar, in September 2015. (

Hayeri

)

“Whatever happens, we had this time together”:

Zakia and Ruqia, at home in Ali’s father’s house in Surkh Dar village, Bamiyan, in September 2015, eighteen months after the lovers eloped. (

Hayeri

)

“Now they will all go to school”:

Ali’s parents, Anwar and Chaman, at home with their newest grandchild, Ruqia, in September 2015. (

Hayeri

)

Birds in a Cage:

Ali trapping quail in the family fields; he keeps birdsongs on his cell phone. (

Quilty

)

“Enmity like this they will never give up”:

Ali working the fields, armed and ready, in February 2015. (

Quilty

).

Still hunted, still in hiding, but happy:

Zakia and Ruqia, whose names rhyme, in September 2015. (

Hayeri

)

Spring of the Persian year 1394 was kind to Bamiyan, thanks to a blessing of late-winter snows and early rains after a season of drought and then perfectly clear blue skies, warm with cool mountain breezes, silver birches in full leaf up and down the lanes, patchwork fields painted in the many shades of verdancy.

1

There was even a dusting of downy green on the barren golden hillsides, good forage for sheep. It was the kind of spring weather that makes lovers fall in love again or reminds them of when they first did. In Surkh Dar the nights no longer needed heating, so Zakia slept with Ali rather than in the warm room with the other women and children. During their “pillow time,” as Ali referred to those minutes before sleep, they reminisced about earlier days, when their love hadn’t yet learned how to walk and talk. What happened to them then was a mystery, and nothing is quite so thrilling to young love as jointly unraveling the clues to their creation story.

“What was it for you?” he asked on one of those nights.

“You were so friendly, and I loved how you behaved to me,” she said.

He didn’t know what to say for his part, but a couple of nights later he remembered the donkey. “For me it was that time on the donkey,” he said.

“The donkey?” She hit him playfully. “Donkey?” But she remembered it, too.

He was still unsatisfied with

her

answer, though; it seemed too vague. A few nights later, he asked her if it was the birds, that time she was watching him playing with his quails when he should have been working in the fields.

“No, it wasn’t the birds,” she said. “It was just your good behavior to me. You were kind, and you had good character. You didn’t take hash or sniff glue or smoke cigarettes like a lot of the other boys.”

“I smoke cigarettes now.”

“You didn’t then, and you should stop.” She was always trying to get him to stop.