The Lucky Baseball Bat (2 page)

“I’m sorry, Mother,” he said. He didn’t want to tell her he had baseball on his mind.

Marvin went outside after supper, and sat on the front porch in the shade. He expected Jeannie as soon as she finished helping Mother with the dishes. For a minute he got to thinking about Jeannie. If she had been a boy everything would have been all right. They could play baseball together, and get a lot of practice, and chum around like real pals. You can’t do those things with a sister, he thought, even though Jeannie tried to be like a boy with him.

He didn’t know how long he sat out there thinking. But all at once he heard leather heels clicking on the sidewalk. They were coming from down the street, and even before he looked to see who was making the sound, he knew who it was. It was Barry Welton.

“Hi, Barry!” he greeted when Barry got closer. It was hard to smile.

“Hi, Marv,” Barry answered. “Taking it easy?”

Marvin nodded. “Wait a minute, Barry,” he said, and went into the house. “I’ll be right back.”

He got the bat and glove and brought them out. “Here,” he said, swallowing a lump in his throat. “Take them back, Barry. They’ll never let me play baseball around here!”

Barry frowned, then a grin came over his face. “Shucks, now, pal. Don’t go acting like that or you’ll never play ball! Have you got a ball?”

“In the house,” Marvin said, wondering what Barry was driving at.

“Get it. We’ll play a little catch.”

Marvin ran into the house, full of excitement. The ball was in the closet where he kept all his things. He brought it out and tossed it to Barry.

“Let’s go out to the side of the house,” Barry said, “so that we won’t be throwing toward the windows. You get over there and I’ll have my back toward the street. Just make sure you don’t throw any wide balls!” he laughed.

“I’ll try not to,” Marvin said, and they started throwing the ball back and forth between them, Marvin using the glove, and Barry barehanded. Marvin thrilled at the expert way Barry was catching the balls, pulling his hands down and away with the ball. He tried to do the same. Only, with the glove, he didn’t have to do it so much.

They played about fifteen minutes, then Barry said he had to move along. He’d see Marvin tomorrow. In the meantime Jeannie had come out to sit on the porch, watching them. After Barry left, Marvin still wanted to play.

“Jeannie,” he said, “how about throwing the ball to me in the back yard? I’ll bat. Then after a while you can bat.”

“Okay!”

He knew she would be willing. She was a swell sister, even if she wasn’t a boy!

Out in the back yard they had much more room. The lawn was bordered by a hedge on two sides. In the back two tall elms with branches spreading out like big, crooked arms would be some protection if a ball were hit that far.

But it was not as much fun as Marvin had hoped. Each time Jeannie threw the ball he swung, and missed. He didn’t want to swing too hard, of course. He might hit it squarely, and send it beyond the trees into the neighbor’s yard. He might even break a window. And that he couldn’t risk.

So he swung only lightly. A couple of times he ticked the ball, and in the beginning he joked with Jeannie.

“Quit throwing those curves!” he’d say.

She would laugh, knowing as well as he that she did not have the faintest idea how to throw a curve.

But then missing the ball four, five, six times in a row got under his skin. Sweat began to break out on his forehead. He was growing warm all over, and he knew it was because he was getting anxious and mad.

“Marvin,” said Jeannie, “what’s the matter? Can’t you even hit it?”

He took one final, hard swing. If he had hit it, it would surely have sailed beyond the big elm trees. But he missed. His bat swished through the air, almost making him lose his balance.

Angrily, he threw the bat to the ground, ran around to the porch, and into the house. He ran to his bedroom, fell on his bed, and no longer tried to stop the tears.

M

ARVIN heard the door open. He didn’t look up. His face was buried in the pillow. He could feel and taste the salty wetness that had soaked into it. The door closed and he heard Jeannie’s voice.

“Marv, don’t cry.”

He didn’t say anything. But hearing Jeannie made him want to stop crying.

He felt her warm hand on his back, rubbing him gently. “Please, Marv. I don’t like to hear you cry. If — if you keep on, I — I’ll probably start crying, too.”

He rolled over on his side and wiped the tears from his cheeks with his wrist. He hated to cry. He was big now. He was ashamed to be letting tears spill all over the place. He got up.

“You’re nice, Jeannie,” he murmured softly.

Jeannie smiled, and he thought she really was going to cry, too.

Then a voice called from the kitchen: “Jeannie! Marvin!”

They ran out to the kitchen. Their mother was in front of the mirror, brushing her hair with short, pulling strokes. She smiled at them, her brown eyes sparkling.

“Want to go to the movies?” she asked.

“Yes!” They said it almost together, their faces brightening up like Christmas-tree bulbs.

“Well,” she said, “wash yourselves and get dressed!”

They washed and put on their best going-out clothes, while their daddy went to get the car from the garage. By the time they were ready he had the car at the curb, a new-looking, pea-green sedan. They all piled in and headed for the movie. Jeannie and Marvin sat in the back seat. They were both very happy, and not once did Marvin think about baseball.

The movie was a comedy. They laughed all the way through it.

Then they talked about it on the way home. Marvin and Jeannie told and retold some of the funniest scenes and laughed about them. It was what they did every time after they saw a movie.

After they were home and in the house awhile Marvin remembered the bat he had left outside. Quickly, he raced out the side door, onto the porch and down the steps to the back yard. The sun had gone down, but the half-moon that hung in the sky looked big and yellow, almost close enough to hang a hat on. It made the trees and the roofs of the houses stand out sharp and black. It helped him see whatever was on the ground.

Marvin searched in and around the spot where he was sure he had left the bat. But it was nowhere around.

The bat was gone!

M

ARVIN could not sleep half the night, thinking about the bat. He thought over and over again how he had missed Jeannie’s pitch, gotten mad, and thrown down the bat. That was a foolish thing to do — he knew that now. He should not have gotten mad in the first place. He should not have thrown the bat aside like that. At least, he should have gone back out right away and brought it into the house.

He would not have minded so much if Barry Welton had not given him the bat. But Barry had — and now it was gone. Somebody must have stolen it. Baseball bats don’t just walk away.

Finally he fell asleep. He dreamed about the movie. He was one of the actors. He saw that another actor had the bat. But when he went to ask for it the actor showed him empty hands.

The next morning after breakfast he went out to the back yard again, just to see if he might have missed the bat last night. It could have rolled behind one of Mother’s rose bushes, or into the higher grass that grew close to the wire fence. But he did not find it. The bat had really disappeared.

He walked out front. The sun, shining over the rooftops, felt hot against his face. He thought about going to the park. Maybe it was too early. Maybe none of the boys would be down there yet. He could not get the thought of the bat out of his mind. What could have happened to it? Did somebody take it? But who? And how?

He walked up to the corner where Ferrin Street crossed Grant. Down the street he saw some boys playing with a tennis ball. He recognized one of them. It was Rick Savora, who lived in the brick tenement house. The porch of the tenement house sagged on one corner and some of its windows were cracked.

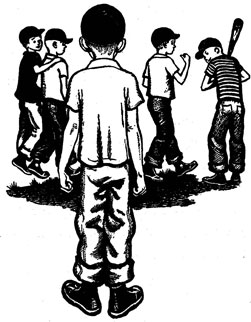

Rick was about eleven or twelve — bigger than Marvin. He stood with his legs spread apart and held a bat on his shoulder, waiting for another boy to pitch him the tennis ball. Way back was another boy, waiting to chase the ball in case Rick hit it.

Marvin stood on the corner and waited to see what Rick would do. Rick, he remembered, was one of the boys at the park yesterday. He looked as if he might be the best player of them all.

Suddenly Rick swung at the ball, hit it, and it went bounding down the street past the pitcher. Rick dropped the bat and started scooting around squares of cardboard which were used for bases.

Then Marvin noticed the bat. It had rolled a little way as Rick had thrown it, and then stopped. Marvin’s heart pounded like mad. He started to walk down the street.

One of the boys saw him.

“Here comes that Allan kid!” he cried out.

Rick stood on second, his hands on his knees as if he were getting ready to run for third. When he heard the boy shout he rose and scowled at Marvin.

“What do you want around here?” he yelled.

Marvin didn’t answer. He looked at Rick and then again at the bat. The more he looked at it the more it looked like the one Barry had given him.

The boys muttered in low tones among themselves. One of them walked off the street. Rick picked up the cardboard piece that was second base, tucked it under his arm, then picked up the bat. He walked off the street, too. The boy who played catcher followed him.

All three gave Marvin dirty looks and went up on the porch of the house, the boards squeaking under their weight.

Marvin stopped and watched them. A hurt look crept into his eyes and an ache filled his throat, wanting to turn into tears. He spun on his heel and headed for home. He walked a little way, then started running. For some reason he could not explain, he wanted to get away from there as fast as he could.

H

E met Jeannie in front of the house, bouncing a rubber ball up and down on the sidewalk. She caught the ball and looked up at him in surprise.

“I was looking for you,” she said.

“Rick Savora’s got my bat!” Marvin exclaimed. “I just saw him take it into the house.”

Jeannie’s eyes widened. “Did you ask him for it?”

“No. I didn’t have a chance. He and some other kids went into his house when they saw me coming down the street.”

Jeannie’s lips tightened. She made a face, and Marvin knew she was disgusted.

“Let’s go to his house and ask him for that bat,” she said.

“Suppose he won’t give it to me?” Marvin asked.

“Then we’ll tell Daddy about it.”

Marvin shook his head. “No. I won’t tell Daddy anything. I don’t want him mixed up in this.”

“Well, let’s go anyway. If it’s your bat he must have stolen it, and he must give it back. I don’t like stealers.”

Together they walked to Rick Savora’s house. The wooden steps creaked as they climbed to the porch. Marvin knocked on the door.

A lady opened it. “Yes?” she said. She brushed a lock of dark hair away from her face, and looked curiously from Jeannie to Marvin.