The Magic Circle (51 page)

Authors: Katherine Neville

Tags: #Fiction, #Thrillers, #Suspense, #Romance, #Historical

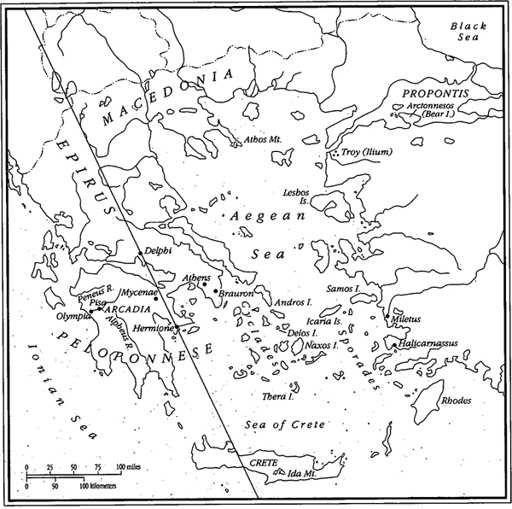

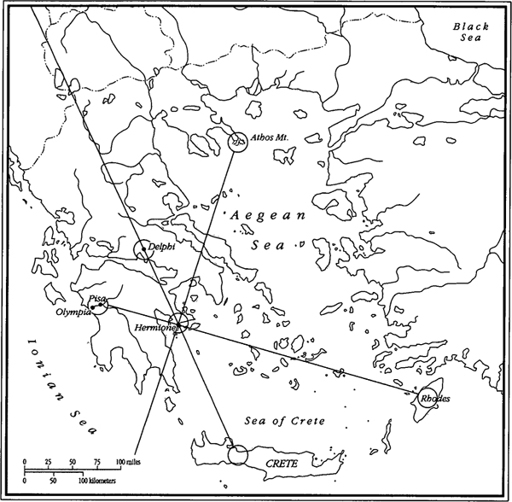

Here was the python-inspired prophetess, the Pythian, the Delphic oracle. For thousands of years, these successive oracular mouthpieces of Apollo had foretold events and prescribed actions the Greeks had adhered to religiously. No ancient writer doubted that the Delphic oracle could see the interconnected web of time comprising past, present, and future. So a site like Hermione, connecting places as important as Delphi and Cretan Ida, may well have been

the

axis.

I drew an invisible X with my finger across the axis, making a six-pointed asterisk, a

Hagal

rune like the one Wolfgang had drawn earlier in the air.

At this point, it seemed far from coincidental that the first line passed through Eleusis, home of the Eleusinian Mysteries, continuing to the Macedonian peninsula where Mount Athos projects into the Aegean—a site plastered here on the map with dozens of tiny crosses. A famous group of twenty monasteries built by the emperor Theodosius, patron of Saint Hieronymus, Athos was once a major repository of ancient manuscripts repeatedly looted by the Turks and Slavs in innumerable Balkan wars. Its unusual location, equidistant from Mount Olympus on the Greek mainland and Troy on the Turkish, was visible from each. Perhaps Athos itself was yet another axis?

The other line of my asterisk was even more interesting. It led to Olympia on the Alphaeus river, home of the Olympic games. I’d been there one weekend after a concert of Jersey’s in Athens. We’d hiked over broken stone beneath Mount Kronos. Aside from Olympia’s famous ruins like the temple of Zeus, there was a relic at Olympia that stuck in my mind: the Heraion, temple of the goddess Hera, wife and sister to Zeus. Though built of plastered wood and less impressive than the Zeus temple, the original Heraion was constructed as early as 1000 B.C. and is the oldest extant temple in Greece.

Then I knew why the name Hermione seemed so familiar (not just familial) to me. In the myths, Hermione was the place Hera and Zeus first landed when they came to Greece from Crete—the entry point of the Olympic gods to the continent of Europe.

Wolfgang, who’d been watching in silence as my finger traced the map beneath the glass, now turned to me.

“Astounding,” he said. “I’ve often walked by this map, but I never saw the connection you’ve seen at first glance.”

A uniformed guard arrived and secured open the high inner doors, and Wolfgang and I entered the gold and white Baroque library of the monastery of Melk. A wall of French windows at the far end overlooked a sprawling terra-cotta-colored terrace; beyond it lay the Danube, its surface glittering like crystals in the morning sun, filling the vast library with bouncing light. As a custodian wiped one of the glass display cases dividing the room, a wiry grey-haired man in a priest’s cassock adjusted leather-bound books on a shelf partway down. He turned as we entered, smiled, and came toward us. He seemed somehow familiar.

“I hope you don’t mind,” Wolfgang said, taking my arm. “I’ve asked someone to assist us.” We went forward to greet him.

“

Professore

Hauser,” said the priest, his English heavily flavored with Italian, “I’m happy you and your American colleague were able to arrive early, as I asked. I’ve already prepared some things for you to see. But

scusa, signorina

, I forget myself: I am Father Virgilio, the library archivist. You will excuse my poor English, I hope? I come from Trieste.” Then he added, with a somewhat awkward laugh, “Virgilio, it’s a good name for a guide: like Virgil in the

Divina Commedia

, no?”

“Was that who escorted Dante around Paradise?” I asked.

“No, that was Beatrice, a lovely young woman I imagine very much as yourself,” he added graciously. “The poet Virgil, I apologize to say, guided him through Purgatory, Limbo, and Hell. I hope your experience with me will be better!” He laughed and added almost as an afterthought, “But Dante had a third guide, as few seem to recall, one whose works are treasured here in our collection.”

“Who was the third guide?” I asked.

“Saint Bernard de Clairvaux. A most interesting figure,” Father Virgilio said. “Though he was canonized, many thought him a false prophet, even the Prince of Darkness. He initiated the disastrous Second Crusade, resulting in the destruction of the Crusader armies and the eventual return of the Holy Land to Islam. Bernard also inaugurated the infamous Order of Templars, whose mission was to defend Solomon’s temple at Jerusalem against the Saracen; two hundred years later, they were suppressed for heresy. Here at Melk we have illuminated texts of the many sermons Saint Bernard delivered on the Canticle of Canticles, and dedicated to King Solomon.”

But as Father Virgilio turned and headed off down the long room, distant bells started clanging in my head, and not for his mention of Song of Songs. As we followed our shepherd, I scanned the books lining shelves to my right and the contents of the imposing glass cases to my left. And I racked my brain, trying to figure out exactly what was bugging me about this black-clad priest. For one thing, Wolfgang hadn’t mentioned any spiritual guide on today’s agenda, nor any knightly orders I ought to be boning up on. I studied Virgilio as we followed him, and all at once I bristled with anger.

Without those priestly vestments—but with the addition of a dark, battered hat—Father Virgilio might well be the spitting image of someone else. Then I recalled that those few whispered words I’d heard in the vineyard last night had been in English, not German. By the time Father Virgilio stopped before a large glass case near the end and turned to us, I was seething with fury at Wolfgang.

“Is this not a great work of art?” he asked, gesturing to the richly detailed hand-colored manuscript beneath the glass as he glanced from Wolfgang to me with dewy eyes and fingered his crucifix.

I nodded with a wry smile, and said in my rusty German:

“

Also, Vater, wenn Sie trun hier mit uns sind, was tut heute Hans Claus?

” (So if you’re here with us now, Father, what’s “Hans Claus” up to today?)

The priest glanced in confusion at Wolfgang, who turned to me and said, “

Ich wusste nicht dass du Deutsch konntest.

” (I didn’t realize you could speak German.)

“

Nicht sehr viel, aber sicherlich mehr als unser österreichischer Archivar hier,

” I told him coolly. (Not very much, but surely more than our Austrian archivist here.)

“I think perhaps you’ve helped us enough for the moment, Father,” Wolfgang told the priest. “Could you wait in the annex while my colleague and I have a word?”

Virgilio bowed twice, said a few quick

scusa

’s, and bustled from the room.

Wolfgang had leaned over the glass case with folded arms and was gazing down at the gilded manuscript. His handsome, patrician features were reflected in the glass. “It’s magnificent, isn’t it?” he observed, as though nothing had happened. “But of course, this copy was executed several hundred years after Saint Bernard’s time—”

“Wolfgang,” I interrupted this reverie.

He straightened and looked at me with clear, guileless turquoise eyes.

“That morning back at my apartment in Idaho, as I recall, you assured me you would always tell me the truth. What exactly is going on here?”

The way he was looking at me would have melted the

Titanic

’s iceberg, and I confess it did a pretty good job on me—but that wasn’t all the ammo up his sleeve.

“I’m in love with you, Ariel,” he said simply and directly. “If I say that there are matters in which you must simply trust me, I expect you to believe me—to believe

in

me. Do you understand? Is this not enough?”

“I’m afraid not,” I told him firmly.

To do him credit, he registered no surprise, just complete attention, as if waiting for something. I wasn’t sure exactly how to say what I knew I must.

“Last night I believed I was falling in love with you, too,” I told him sincerely. His eyes narrowed, as they had when he’d passed me that first day in the annex lobby. But I couldn’t hold back my frustration. “How could you make love to me that way,” I said, glancing to be sure no one could overhear, “then turn around and lie to me, as you did in the vineyard? Who is this damned ‘Father Virgilio’ following us around like a wraith?”

“I suppose you do deserve an explanation,” he agreed, rubbing one hand over his eyes. Then he looked at me again with an open expression. “Father Virgilio truly is a priest from Trieste; I’ve known him for years. He has worked for me, though not in the capacity I told you earlier. More recently, by doing research here in this library. And I did want you to meet him—but not late last night when I had … other things in mind.” He smiled a little self-consciously. “After all, he

is

a priest.”

“Then what was all that Hans-Claus business this morning, if you knew we were coming here to meet him?”

“I was worried last night, when you thought Virgilio looked familiar,” Wolfgang said. “Then this morning, when I made that slip and you pursued it, it was already too late to change plans. How could I imagine you’d be able to recognize him from earlier yesterday, just by one glimpse in darkness last night, and at such a distance?”

I was getting that déjà-vu-all-over-again feeling as I racked my brain for when I’d seen Father Virgilio “earlier.” But I didn’t have to ask.

“You have every right to despise me for what I’ve done,” said Wolfgang apologetically. “But it was at such short notice, when I learned I wouldn’t be joining you and Dacian Bassarides for lunch—that man is so unpredictable! I shouldn’t have been surprised if he’d spirited you away and I’d never seen you again. Luckily, I had chosen a restaurant where they knew me well enough to accept Virgilio as a ‘temporary employee’—to look out for you during the afternoon—”

So

that

was it! No wonder he’d seemed familiar to me in the vineyard. In my frenzied preoccupation yesterday afternoon at the Café Central, I’d hardly glanced at the faces around me, yet I must have registered that same figure performing some service around our table perhaps half a dozen times. Now, torn between relief and worry, I wondered just how much our impromptu busboy had overheard of our luncheon conversation. Though it seemed Wolfgang had only been trying to protect me from the vagaries of my unknown grandfather, I cursed myself for not being more vigilant, as Sam had taught me all through childhood.

But I had no chance to dwell on these thoughts. Father Virgilio, peering through the entrance doors, seemed to have decided that adequate dust had settled to cushion his return. Seeing him, Wolfgang bent toward me and spoke quickly. “If you can read Latin half as well as you speak German, I shouldn’t comment in front of Virgilio on the first line of this manuscript of Saint Bernard’s: it might embarrass him.”

I looked down at the book and shook my head. “What does it say?”

“‘Divine love is reached through carnal love,’” said Wolfgang with a complicitous smile. “Later, when we’ve a free moment together, I’d like to test that theory.”

Father Virgilio had arrived with a map of Europe, a modern one. He unfolded it on a trestle table before us and said, “It is important that from ancient times a mysterious tribe in this region held the female bear as their totem, and that they were possessed of an almost mystical reverence for a substance with many alchemical properties: salt.”

THE BEARS

At age seven, I carried the sacred vessels … when I was ten I was a bear girl of Artemis at Brauron, dressed in the little robe of crocus-colored silk

.

—Aristophanes,

Lysistrata

Bernard Sorrel—the saint’s family name—was born in

A.D

. 1091, at the dawn of the Crusades. On his father’s side he was descended from wealthy nobles of the Franche-Comté, on his mother’s from the Burgundian dukes of Montbard—“bear mountain.” The family castle, Fontaines, was situated between Dijon in northern Burgundy and Troyes in the province of Champagne—a region of vineyards planted from Roman stock that were consistently under cultivation since ancient times.

Bernard’s father died in the First Crusade. The young man suffered a nervous collapse when his beloved mother died also, while he was away at school. At the age of twenty-two, Bernard joined the Benedictine monks. Always of fragile health, he soon became ill, but was given a small cottage on the nearby estate of his patron Hugues de Troyes, count of Champagne, where he recuperated. The following year Count Hugues visited the Holy Land to see at first hand the Christianized kingdom of Jerusalem that had been established after the successful First Crusade. On his return, the count at once ceded part of his property to the Church: the wild valley of Clairvaux branching off the river Aube. There, at age twenty-four, Bernard Sorrel established an abbey and became first abbot of Clairvaux.