The Magic Circle (52 page)

Authors: Katherine Neville

Tags: #Fiction, #Thrillers, #Suspense, #Romance, #Historical

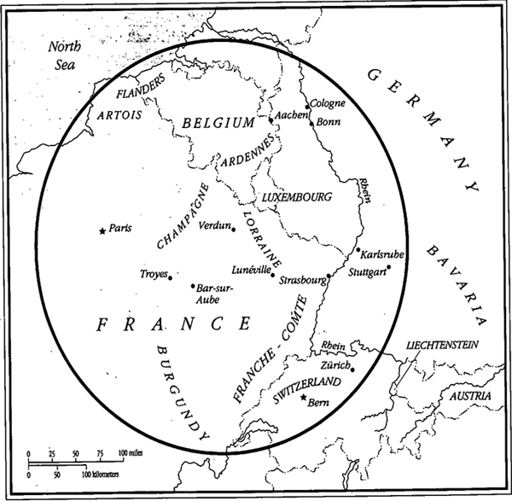

It is relevant to our story that Clairvaux is situated at the heart of the region that in ancient times encompassed today’s French Burgundy, Champagne, Franche-Comté, Alsace-Lorraine, and adjacent portions of Luxembourg, Belgium, and Switzerland. This region was once ruled by the Salii, whose name means People of the Salt. These Salic Franks, like the Roman emperors from the time of Augustus, claimed their ancestors came from Troy in Asia Minor—as place-names on the map like

Troyes

and

Paris

attest. Ancient Troy itself had profound connections to salt. Bounded on the east by the Ida range of mountains, its

Halesian

plains are watered by the

Tuzla

River, whose pre-Turkish name was

Salniois

—all these names meaning salt.

The Salii claimed that their ancestor Meroveus, “Sea-Born,” was the son of a virgin who’d been impregnated while swimming in salt water. His descendants, the Merovingians, lived in the time of King Arthur. They were believed, like the British king, to possess magical powers associated with the polar axis and its two celestial bears. The name Arthur means bear, and the Merovingians took for their battle standard the figure of an upright female fighting bear.

This connection between salt and bears goes back to two goddesses of ancient mystery. The first is Aphrodite who, like Meroveus, rose “foam-born” from the salt sea. She is ruler of both the dawn and the morning star. The other is Artemis, the virgin bear goddess, whose symbol is the moon, which nightly pulls the tides of the sea. This forms an axis between dawn and night, and also between the celestial pole of the bear and the fathomless sea.

It’s no accident that many place-names in the region just described are connected with aspects of these two.

Clairvaux

itself means vales of light, and the

Aube

, the river at Clairvaux, means dawn. Of equal or greater importance then there are those names beginning with

arc-, ark-, art-, or arth-

, like the

Ardennes

, named after

Arduinna

, a Belgian version of Artemis—and the German

bär

or

ber

found in place-names like

Bern

and

Berlin

. All these names, of course—like Bernard’s itself—mean bear.

In his first ten years as abbot, Bernard de Clairvaux rose swiftly—one might say miraculously—to become the leading French churchman, a confidant of popes. When two popes were elected by separate contingents of Italians and French, Bernard healed the schism and got his own candidate, Innocent II, seated on the pontifical throne. This success was followed by the election of a former Clairvaux monk, Eugenius, as the next pope, for whom Bernard preached the launching of the Second Crusade. Bernard was instrumental, too, in gaining Church sanction for the Knights Templars, an order founded jointly by his uncle André de Montbard and his patron Count Hugues de Troyes.

The Crusades began a millennium after Christ and lasted some two hundred years. Their mission was to reclaim the Holy Land from the “infidel,”

al-Islam

, and unite the Eastern and Western churches, Constantinople and Rome, with a common focal point in Jerusalem. Of specific importance was to gain Western control of key religious sites, like Solomon’s temple.

The real Temple of Solomon, built around 1000 B.C., was destroyed by the Chaldeans some five centuries later. Though it was rebuilt, many holy relics already were reported missing, including the Ark of the Covenant from the time of Moses, which had been brought back to Jerusalem by Solomon’s father, David. This second temple, refurbished by Herod the Great just before the time of Christ, was razed by the Romans in the Jewish Wars of

A.D

. 70 and never rebuilt. So the “temple” guarded by the Templars in the Crusades was actually one of two Islamic structures built in the eighth century: the

Masjid el-Aqsa

, or Farthest Mosque, and the slightly older Dome of the Rock, site of David’s threshing floor and of the Hebrews’ first altar in the Holy Land.

Beneath both these sites ran a vast man-made system of water conduits, caves, and tunnels, begun before the time of David and mentioned many times in the Bible as honeycombing the entire Temple Mount. In these catacombs also lay “Solomon’s stables,” caves used by the Knights Templar, reputedly capable of sheltering two thousand horses. One of the Dead Sea Scrolls from Qumran, the Copper Scroll, lists an inventory of treasure once hidden in these caves, including many ancient Hebrew holy relics and manuscripts, and the spear that pierced the side of Christ.

This spear was discovered by the first Crusaders while besieging Syrian Antioch. Trapped by Saracens for over a month between the inner and outer siege walls, the Crusaders resorted to eating horses and pack animals, and many died of starvation. But one monk had a vision that the famous spear was buried in the Church of St. Peter beneath their very feet. The Crusaders exhumed the spear and bore it before them as a standard. Its powers enabled them to conquer Antioch and march on successfully to storm Jerusalem.

The name Frank—

Franko

in Old High German—meant spear, while the Franks’ neighbors, the Saxons, were called

Sako

, meaning sword. These tribes of Germanic warriors proved so formidable that Arab chroniclers called

all

Crusaders Franks.

“Although the Second Crusade, propagandized by Bernard de Clairvaux, had proved a disaster,” Father Virgilio concluded, “the Templars continued to flourish throughout his lifetime. The abbot of Clairvaux then set himself the curious task of writing one hundred separate allegorical and mystical sermons on the Song of Songs, of which eighty-six were completed at his death. More peculiar still is the fact that Bernard is known to have identified himself with the Shulamite, the black virgin of the poem—with the Church, of course, identified with Solomon, her beloved king. Some believe the Songs are an encoded form of an ancient esoteric initiation ritual which once provided a key to the mystery religions, and that Bernard had deciphered it. Yet the Church’s regard for Bernard was such that he was canonized only twenty years after his death in 1153.”

“What about the Order of Knights Templar that he helped launch?” I asked him. “You told us that later they were convicted of heresy and wiped out.”

“Hundreds of books have been written on their fate,” Virgilio said. “It was chained to a star that rose swiftly, burned brightly for two centuries, then vanished as quickly as it had come. Their initial charter from the pope was to protect pilgrims traveling to the Holy Land, and to secure the Temple Mount. But these Poor Knights of Jerusalem and the Temple of King Solomon soon became Europe’s first bankers. They were eventually ceded properties amounting to a tithe by the crowned heads of Europe. Highly political, they held themselves independent of Church or State. Eventually the Templars were charged by both these institutions with heresy, treason, and deviant Satanic sexual practices. They were rounded up to a man, and tortured and burned at the stake by the Inquisition.

“As for the Templars’ vast hoards of treasure,” he added, “these reputedly included holy relics possessing enormous powers, like the sword of Saint Peter and the spear of Longinus, not to mention the Holy Grail itself—relics that were sought by courtly knights throughout the Middle Ages, from Galahad to Parsifal. The whereabouts of this treasure, however, is a mystery that remains, down to the present, unresolved.”

Of course, I hadn’t overlooked the parallels between Father Virgilio’s medieval whodunit and all the previous details dropped by everyone else. There were the references to Solomon and his temple, tying them to everyone from the Queen of Sheba to the Crusaders. But Virgilio’s tale seemed also to point elsewhere: once again, to a map. Though I couldn’t see the whole pattern, I was hoping at least to tie up a few loose threads. Then Wolfgang did it for me as we looked at Virgilio’s map before us on the trestle table.

“It’s incredible the way things leap out, when you look at a map,” Wolfgang said. “I now see how many of the old epics—the Icelandic Eddas, even the earliest Grail legends of Chrétien de Troyes—describe battles and adventures that are centered on this one region. When Richard Wagner wrote the

Ring

cycle that Hitler admired so much, he based it on the Germanic epic the

Nibelungenlied

, which tells how the Storm from the East, Attila the Hun, was fought by the Nibelungs—who were none other than the Merovingians.”

“But all that happened long before the Crusades,” I pointed out. “Even if we’re talking about the same piece of turf, how does it relate to Bernard or the Templars, hundreds of years later?”

“Everything,” said Virgilio, “is shaped by what went before. In this case, it relates to three kingdoms: the one established by Solomon’s father, based in Jerusalem; the kingdom set up by the Merovingians in fifth-century Europe; and the Christian kingdom of Jerusalem, founded five centuries later in the Crusades, by men who came from the same region of France. There are many theories, but they all pertain to one thing: the blood.”

“The blood?” I said.

“Some claim the Merovingians carried sacred blood,” Virgilio explained. “A bloodline descended perhaps from Christ’s brother James, or even from a secret marriage between the Magdalene and Jesus himself. Others say the blood of the Saviour was collected by Joseph of Arimathea in the Holy Grail, a vessel later taken by the Magdalene to France and preserved against a day when science could restore a human being to flesh.”

“You mean, like DNA re-creation, or cloning?” I said with a grimace.

“Such views, of course, are not only heretical but, if I may say so, rather foolish,” said Virgilio with a wry smile. “There is one curious fact we

do

know about bloodlines: that all the kings of Jerusalem over the years of Christian rule were descended from one woman, Ida of Lorraine.”

It hadn’t escaped my attention that there were two Mount Idas of importance. The first, on Crete, was the birthplace of Zeus, a major site of Dionysian worship, and also connected to Hermione on the map. The second, on the coast of modern-day Turkey, was the site of the Judgment of Paris; from it the gods had watched the progress of the Trojan War. And now a third Ida, according to Virgilio, was the ancestress of every king who’d ruled Jerusalem for two hundred years. A woman from the very region we’d spoken of. And apparently that wasn’t all.

“The big story of the high Middle Ages in Europe,” said Virgilio, “was not the Crusades, but rather the blood feud between two families known in history books by the Italian names Guelphs and Ghibellines. They were actually German: Bavarian dukes called

Welf

, meaning whelp or bear cub, and Swabian Hohenstaufens called

Waiblingen

, or honeycomb. One man alone, coincidentally also a protégé of Bernard de Clairvaux, combined the blood of these adversaries. This was Frederick Barbarossa, who survived Bernard’s disastrous Second Crusade to become Holy Roman Emperor.

“As the first ruler to unite in his veins the powerful bloodlines of those two Germanic tribes, whose private battles had defined the history of the Middle Ages, Barbarossa was regarded as the saviour of the German people, someone who would one day unite them to lead the world.

“He went on to forge Germany into a major power, and to launch the Third Crusade at age sixty-six. But en route to the Holy Land, he mysteriously drowned while bathing in a river in southern Turkey. His famous legend maintains that Barbarossa sleeps today within the mountain of Kyffhäuser in the center of Germany, and that he’ll rise to come to the aid of the German peoples in their hour of need.” Virgilio folded his hands on the map and asked me, “Does it remind you of another story?”

I shook my head as Wolfgang placed his finger on the map and slowly traced a circle around the region Virgilio had spoken of. I froze at his next words.

“According to Hitler’s architect, Albert Speer,” Wolfgang told me, “it’s precisely this area where Heinrich Himmler wished to create, after Germany’s victory in the war, an ‘SS parallel state.’ Himmler planned to put high-ranking storm troopers there with racially pure wives selected by the genealogy research branch of the SS, and to form a separate Reich comprised of them and their children. He wished to purify the blood and reawaken the ancient mystical ties to the land—blood and soil.”

I looked at him in horror, but he wasn’t quite through.

“This is also certainly why Hitler called his attack to the east Operation Barbarossa—to awaken the waiting spirit of the emperor Frederick, long asleep within the mountain. He wished to invoke the magical blood of the long-lost Merovingians. To bring forth a utopian new world order, based on blood.”

THE BLOOD

It was believed that the blood in [the Merovingians’] veins gave them magical powers: they could make the crops grow by walking across the fields, they could interpret bird-song and the calls of the wild beasts, and they were invincible in battle, provided they did not cut their hair

.…