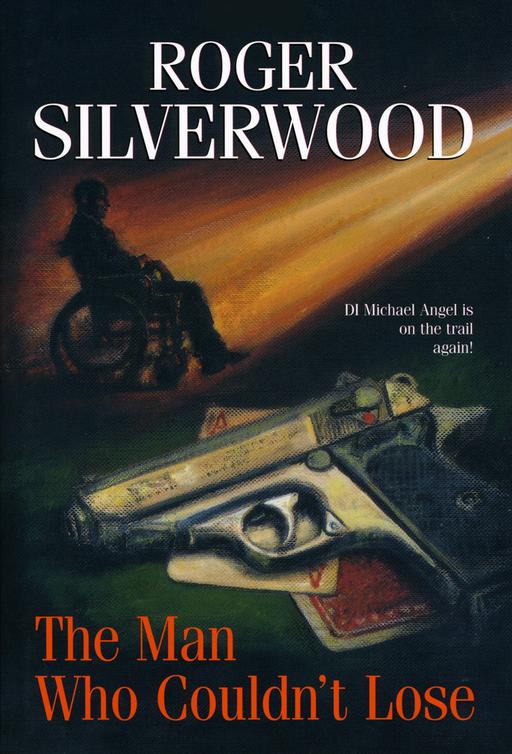

The Man Who Couldn't Lose

Read The Man Who Couldn't Lose Online

Authors: Roger Silverwood

Couldn't Lose

Roger Silverwood

Bromersley, South Yorkshire, UK, 23.15 hours, 18 October 1970

The young couple were in the dark, sheltered archway of the Theatre Royal on Bradford Street, leaning against the closed emergency-exit door. The second house had long since finished. The theatre had emptied. The lights were out. The street was deserted.

His arms were round her, and he pressed his hard body against her and gave her a long, tender kiss. When their lips parted, she sighed, and ran a hand through his hair. He was a big, strong, athletic young man with a distinctive lined face.

âJoshua,' she whispered breathily.

Through the darkness he could just see the whites of her big eyes. He sighed, smiled, pulled her back to him and nuzzled into her hair while his fingers eagerly explored her vertebrae; at the same time, she rubbed her hands up and down his arms and shoulders. The only sound to be heard was the heavy breathing and pounding of their hearts. Their loving thoughts were turning to ecstatic dreams as they floated gently in each other's arms.

Suddenly, there was the loud bang of a door being shut, close by, followed by a rattle of keys, then the sound of heavy shoes on stone steps.

They came back abruptly to earth. They froze in the dark shadow of the doorway, hoping not to be discovered.

Someone had come out of the front door of the theatre and was standing on the pavement.

They turned and edged forward. They could just see his outline in the moonlight. He was a portly man in a long coat. At the same moment, a car raced up seemingly from nowhere and stopped at the door with a squeal of brakes. The driver got out, leaving the engine running, and came round to the theatre door. The headlights showed him to be a slim man in a light-coloured raincoat.

The young couple, only twelve feet away from the car, held on to each other motionless, yet listening, wishing the two men would go away and leave them undisturbed.

âYou are late,' the hard voice of the younger man began quietly.

âGot held up.'

âGot the money?'

âGot the stuff?'

âYes.'

âWhere is it?'

âIn the boot.'

âShow me.'

There were footsteps to the back of the car. There was a click of a catch as the boot lid was raised.

âWhere?'

There was no reply.

Suddenly, there was a gasp and the older man said, âWhat's that? No!' he said urgently. There was fear in his voice.

The younger man's voice hardened.

âDrop the money in the back and step away from the car.'

âNo.'

âDo as I tell you.'

âIf you pull that trigger, you'll waken half the town. The cops'll be here in no time.'

âI mean it. Do as I say.'

âYou wouldn't dare.'

âPut that down! Stand back!'

âNo.'

âDrop it or I shoot.'

Then there was the clatter of metal hitting metal, the whooshing of a .202 leaving the barrel of a Walther PPX fitted with a silencer, the rattle of an iron bar clattering on the road, followed by the sound of two men slumping to the ground.

The young couple in the shadows of the doorway stood motionless, their lungs tight with air.

The only sound to be heard was the ticking of the car engine.

The young man disentangled himself from the girl and peered round the corner of the doorway.

âWhat's happened?' she whispered.

âStay there, Myra.'

Joshua looked down at the two men. One lay on top of the other. They were motionless. An iron bar lay on the road, reflecting the light.

He licked his lips. Then stepped gingerly out from the safe cover of the doorway onto the pavement. He looked up and then down the short street. All was quiet. The noise of the pistol shot didn't seem to have disturbed anybody. He leaned over the two men and rubbed his chin. He touched the neck of the younger man, searching for a pulse. His fingers felt hot and sticky. He was touching blood. It was oozing out of the man's head and running down his neck. Joshua gasped. He unrolled the man's fingers from round the Walther PPX and shoved it into his pocket. He picked up a brown paper parcel from the road and threw it in the car boot. Then he went deftly through his pockets and found a wallet. He pushed the younger man off the top of the other man with his foot and then swiftly crouched down and lifted his wallet from his inside pocket.

He saw Myra's feet. She was standing next to him, hands in her pockets.

âAre they dead, Joshua?' she said.

He looked up at her.

âYes,' he said quickly.

âOh,' she gasped. âAre you sure?'

âGet in the car.'

âWhere's the nearest phone?'

âGet in the car,' he snapped. âHurry up.'

âWhat you going to do? Aren't you going to phone the police?'

â

Get in the car

!' he bawled.

They heard the clatter of footsteps running in the distance.

His pulse raced.

Myra hesitated.

âWhat you doing?' she said, her eyes flashing.

Joshua opened the car door

âThis is our chance!' he yelled.

He pushed her into the car.

The running footsteps were louder.

Joshua dashed round the rear of the car, skirting the two bodies and accidentally kicking the iron bar as he scrambled to the driver's door.

Lights inside the foyer of the theatre burst into life. The silhouette of a man's head and shoulders was framed in the glass door.

Joshua saw him and it made him catch his breath. His heart pounded.

He slammed the car door shut; his hands were shaking.

âThere's somebody coming,' Myra squealed.

He fumbled in the dark to find the clutch, the gear stick and then the handbrake; the big car jerked with a loud squeal of rubber away from the kerb into the night.

Sebastopol Terrace, Bromersley, South Yorkshire, UK, 13.15 hours, 19 March 2007

Joshua Gumme, sitting in the back of the Bentley, pressed a button on the armrest and lowered the internal privacy window behind the driver.

âStop here. Number thirteen. This is the one, Horace,' he growled.

âYes, Mr Gumme.'

âHurry up and get my chair out.'

âYes, Mr Gumme.'

Horace âHarelip' Makepiece pulled on the handbrake of the Bentley outside the little terraced house and switched off the ignition. He dashed out of the driver's seat, slammed the door, rushed to the rear of the limo, opened the tailgate and lifted out a wheelchair. He bounced the wheels on the pavement, pressed down the seat to open it and make it rigid and then manoeuvred it up to the nearside rear door of the car.

Joshua Gumme, immaculately dressed in a plain clerical grey three-piece suit, white shirt, dark tie and black Homburg, smart as paint but forty years out of date, swung his large frame out of the car on to the wheelchair and immediately rolled the wheels impatiently towards the door of the little house.

Makepiece closed the boot and the car door and dashed across the pavement to grab hold of the wheelchair handles.

They were soon at the house door. They didn't have to knock. It was swiftly opened by a slim young woman in a shapeless dress, sloppy sandals and with mousey-coloured hair, a clump of it flopping across one cheek. She was wearing a delicately carved necklace comprising twenty or more small heart-shaped garnets, each in a delicate old gold setting and connected by pretty leaf motif chain links. Her face was red and sweaty; her eyes were tired. The chatter of children and occasionally playful screaming could be heard from the kitchen behind her.

âYes?' she said commandingly, looking down at Gumme in the chair then glancing at Makepiece standing behind. âYou're back again. What you want? My husband's out, looking for work. And if you're wanting money, we haven't got any.'

Gumme's lips tightened. He cleared his throat.

âYoung lady,' he began sternly.

She put her hands on her hips and said, âWe're never going to be able to pay you any more, Mr Gumme.'

âMrs Tasker,' he said icily. His eyes suddenly alighted on the garnet and gold necklace twinkling slightly on her white chest. His eyes narrowed as he looked at it but he said nothing. He looked quickly up into her face.

âYes. I'm Mrs Tasker,' she said proudly. âAnd I've got two children to show for it. And my husband can't possibly pay you.'

âYes, well,' he replied, rubbing his chin. âWe'll see about that. I'll come back when your husband's in,' he said curtly.

âHe's out looking for work,' she said, running the tip of her tongue lightly across her lips.

He looked back at Makepiece and waggled a finger.

âGive her a card,' he snapped.

Makepiece whisked out his wallet, found a business card and passed it over to Mrs Tasker.

She wrinkled her nose as she took it.

âTell him to phone me at that number, tonight, Muriel,' Gumme said, staring hard into her face. âTonight!' he repeated loudly. Then he whisked the wheelchair through 180 degrees, dragging Makepiece round with him, and pushed the wheels vigorously towards the car.

Muriel Tasker shivered and felt her pulse quicken. She went back inside the house, closed the door and leaned back against it, breathing unevenly with a hand on her chest.

Doncaster Rail Station, South Yorkshire, UK, 08.40 hours. 20 March 2007

The voice on the tannoy bawled out: âThe train arriving on Platform One is the 6.05 from King's Cross.'

A few people were waiting on the platform to greet it. Among them was a big man who was leaning against a pillar in front of the waiting room reading the

Sporting Life

. As the train rolled in, he stuffed the newspaper into his jacket pocket and stepped forward.

Carriage after carriage rolled past with passengers gathering at the doors.

The train squealed to a halt.

At one door, a severe-looking man in large black hat, clerical collar and black suit, carrying a large black case, an umbrella and a black book inscribed in gold leaf with the words âHoly Bible', descended the steps.

The big man saw him and rushed forward. He looked round to see who was near and then, in a loud voice, said, âAre you Father Ignatius of the Little Brothers Of The Poor?'

The man in the black suit and the clerical collar smiled graciously down at him and said, âIndeed I am, my son.'

The man nodded and returned the smile. He didn't know why. He didn't feel like smiling.

Out of the corner of his mouth, the man in black said, âWhy don't you offer to take my suitcase, you great lump-head?'

The big man's eyes froze momentarily. He knew not to mess with the man in the black hat.

âOh. Can I take your case, good Father?' he stammered loudly.

âVery well, my dear friend,' the man replied with a show of teeth and a flourish of the hand. âI am sure that your kindness to a humble cleric will be rewarded in heaven.'

âOh?' He blinked and bowed. âYes, sir. Thank you. This way, Father.'

The big man bustled along the underpass with the case, and up the steps through the ticket barrier to a car waiting outside, while the man in black strode slowly and deliberately behind him in his own time, gripping the Bible in one hand and using the umbrella as a walking stick. The big man unlocked the car, put the case in the car boot, then opened the front nearside door for the man and waited by it. The man in black ignored the open door and instead opened the offside rear door. He wedged the umbrella between the seats, climbed into the car and, nursing the Bible on his lap, reached out and closed the door. The big man, seeing what had happened, closed the door, ran round the car and got in the driver's seat.

Once they were on their way, the man in black said: âNow remember, you always call me Father Ignatius. OK?'

âWhatever you say, boss,' he said, without thinking.

The eyes of the man in black glowed like hot cinders. His fists tightened. âI said you call me Father Ignatius, you bloody idiot!' he hissed like a snake about to bite.

When the driver realized what he'd said, his blood turned to ice. He licked his lips and gripped the steering wheel more tightly.

âSorry, sir. Father Ignatius, I mean.'

The man in black sighed heavily.

They travelled the ten miles to Bromersley in silence. It was only when the driver stopped outside the front door of the Feathers Hotel that the man in the cleric's clothes said, âNow listen, son. And listen good. You know nothing about me. If you are asked by the police, or anybody else, all you know about me is that my name is Father Ignatius and that I come from Ireland. That's all you need to know. If I find you've been shooting your mouth off, I shall come looking for you. Understand?'

The man's blood ran cold. He sat in the driver's seat as still as a corpse and wished he was anywhere but there.

âYes. Sure. Father Ignatius.'

âRight. And don't phone me.

Never

phone me. If I need

you

, I'll contact you. Right?'

âRight. Yes. Sure, Father Ignatius.'

He slammed the car door and shot into the The Feathers.

The driver watched him swish through the revolving doors. He sighed, grabbed himself a can of Grolsch from under the dash, tore off the ringpull, slung it through the window, took a big swig from the can and then hopped out the car to open the boot as the hotel porter appeared.

There was a card on the lift doors that read, âOut Of Order', but old Walter, the hotel porter, wasted no time and bustled up the stairs with the suitcase to room 102, closely followed by the man in black.

The old man led him into the room, put his luggage on the case stand and said, âDinner is served from six until eight-thirty, and room service is all day until ten o'clock. Will there be anything else, sir?'