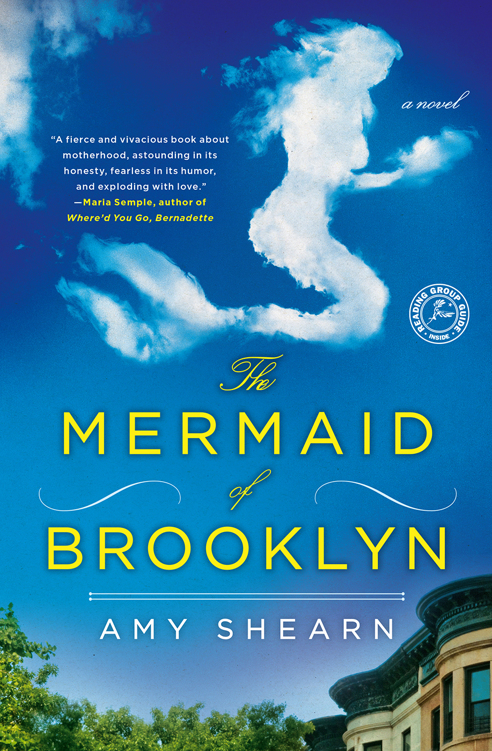

The Mermaid of Brooklyn

Read The Mermaid of Brooklyn Online

Authors: Amy Shearn

Thank you for downloading this Touchstone eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Touchstone and Simon & Schuster.

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

For Adam, Harper, and Alton, the loves of my life: thank you for not being the family in this book

Before I died the first time, my husband left me broke and

alone with our two tiny children and it made me feel very depressed, etc. It’s the same old story: He went to buy cigarettes and never came home. Really. Wouldn’t you think you’d want to pack a bag or two, leave a forwarding address? Couldn’t he have at least taken the dog? These were the things I wondered in the beginning. Not: was he having an affair, or: was he mixed up in something nefarious, but: I can’t believe he wouldn’t bring his datebook, his favorite loafers; I can’t believe he didn’t change the lightbulb in the hallway before deserting us. He knew I couldn’t reach that lightbulb. The whole thing was unlike him. Then again, I was the one who died, which was unlike me, too.

I would be lying if I said his leaving wasn’t a tiny bit of a relief, at least at first. My initial thought—due mostly to sleep deprivation, the effects of which, as any mother or political prisoner knows, never entirely fade—was that once the girls were in bed, I could ignore the dishes to be done and laundry (still in a compact three-day-old brick from the Laundromat drop-off service) to be put away; I could take a bath and then sleep (until Rose’s next feeding) in a big empty bed with pillows mounded up on either side. I

wouldn’t need to make a grown-up meal for Harry, who annoyingly preferred dishes seasoned with things other than butter, and who inconveniently favored dinner conversation consisting of topics other than whether or not mermaids existed and, if so, whether or not their mommies made them take baths. I would not need to stifle the yawns that he mistook for boredom as he dramatically recounted the undramatic details of his day. I would not need to come up with a compelling excuse to avoid sex and then feel guilt both at the refusal and at the unoriginality of the desire, the undesire.

I know this doesn’t make me sound like the nicest wife. But back then I only thought he was late coming home from work. I didn’t know he would be gone so very long, that it would take him months and months to battle his way home, as if he were returning from the Crusades and not the Ever So Fresh Candy Company headquarters in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn. It didn’t occur to me that nothing would ever be the same.

I forgot and didn’t remember for some time that I actually had spoken to him on the evening in question. My days had a habit of bleeding together, and it was often difficult for me to pinpoint whether we had indeed talked a few hours earlier or whether I was remembering the day before. But no, I think it was that night, that fateful night, when, believe it or not, it was raining ominously, a storm of Great Plains–style velocity, unleashed by restless nymphs polluting the city’s clouds, must have been, because there was such vindictiveness in the thunder rattling the kitchen window and spooking the imminently spookable baby so that she was wailing into my collarbone as I called Harry’s phone, wanting to know if (oh God, so typical) he could pick up some milk, a request that was met with irritation—he didn’t see why I couldn’t take care of these things without involving him. Betty sat on her booster seat,

swinging her legs with a buoyancy that belied her scowl. I looked over just in time to see her open her mouth and hatch a mound of chewed grilled cheese onto the table.

“Jenny?” Harry answered, sounding confused. “Is everything okay?”

“Oh, sure. Just another day in paradise,” I said. Rose quieted, distracted by a hank of my hair.

“I miss you,” Harry said. “I miss the girls.” He sounded sad, or maybe just tired.

“Well, you’re in luck,” I said. “We’re all right here, and we’re taking visitors.”

“I wuv you, you wuv me,” Betty sang to her grilled cheese. The girl had a passion for dairy.

“Shh, baby, please,” I said to her, to Rose, to the thunder that grumbled a little farther in the distance now, to the world. “What, Harry? I’m losing you.”

“I’m going to stop for cigarettes on my way home,” it sounded like he said.

“So you’re not quitting, then,” I said, having forgotten all about the milk. I would remember only when I poured my dinner bowl of Cheerios at eleven p.m., which I ended up eating with water, as I’d done more times than I cared to admit. Then he was gone. He would stay that way for a while.

When Harry left and I died it was the beginning of a desperately hot summer, a long sun-scorched stretch of days determined to silence doubters of global warming. The sidewalks of Brooklyn baked all around us, Prospect Park an expanse of brownish hay. I had these two babies, and people were always saying that my whole life was ahead of me—nosy grandmothers on the subway tugging

at Rose’s bootie or boinging Betty’s curls, neighborhood eccentrics dispensing unsolicited advice from their bodega-front benches. I nodded and thanked them, or sometimes rolled my eyes.

My life with Harry had begun five years earlier, right around the time I started feeling my biological clock doing the

My Cousin Vinny

thing. I was working an exhausting job at a magazine that I was just starting to realize was not going anywhere: not the magazine, not the job, not me. I was officially Single and Loving It but in reality too tired by the end of the day to do anything more fabulous than drag myself home and watch fabulous amounts of television. (Romantic comedies counted as educational if they were in black and white. “We all go haywire at times, and if we don’t, maybe we ought to,” I’d mouth along with

The Philadelphia Story

.) I was too old to still have a roommate who called it “cooking” when she added pepper to her ramen; I was too young to retreat to the Midwest, capitulating to a life with many cats. It is annoying to find yourself living a cliché. It is doubly annoying to turn your life upside down only to settle into a fate even more banal than the one you were trying to avoid.

I met Harry on my thirtieth birthday, which I took as an omen. It was a few weeks after September 11, the bad one, and everyone in the city was feeling existentially wigged out, nostalgic for things we’d never noticed before. There was a barbecue on one of the last warm days of the year in someone’s closety backyard, morning glory strangling the brick. (“Those vines are lovely,” I told my host, trying to be friendly. She’d frowned, confessed, “They’re killing

every

thing.”) I didn’t know these people well, but in those weeks everyone was overly solicitous and given to gallows humor, getting together to consume comfort food and avoid the subjects of death and patriotism in favor of those vaguer favorites, What Was So Great About Our City and The Things That Really Mattered. It

smelled like burning rubber in Brooklyn. Every night I dreamed I had children who got lost in my pockets. In other words, it was a dangerous time to meet someone new.

Over by the fence was Harry. He was wearing a leather jacket that was too warm for the weather, which I didn’t question at the time. His white shirt gaped open at the collar. I first noticed that triangle of neck. He stood talking to a trio of pretty blondes, and I couldn’t hear what he said but all at once, as if choreographed, they threw back their heads and laughed. Here was Harry in one of his—of course I couldn’t have known this then—manic highs, characterized by bravado and boisterousness, beloved by all. I thought (ha! ha!),

There is an uncomplicated man

. Having split recently from a morose Bushwick-loft-inhabiting artist, I looked at Harry and my gut said,

I know him

.

He is happy. He knows

(he knocked back a swig of microbrewed beer, squinted at something over my head, the fire escape maybe)

how to enjoy life

. People are always saying to follow your gut. Unfortunately, as it turns out, my gut is kind of stupid.

You know you’re in trouble when you refer to your own relationship as a “whirlwind romance.” Harry was fond of this phrase, which to me stank with a rot-sweet whiff of desperation. It’s true that it all happened very quickly. There was something deeply flattering about his passion for me, how he had to have me immediately and forever. His professions of affection were always larger than life. Two dozen white roses would greet me at work on a gloomy Monday, to the cooing envy of my coworkers. Or I’d wake on a weekend to a homemade cappuccino, a new pair of golden gladiators (he’d pinpointed my weaknesses), and marching orders—“Get up, get up! We’re going on a helicopter tour of the city in an hour!” My therapist posited that Harry was the Un My Father, what with his charisma and spontaneity and vague sheen of hazard.

She called him the Prince of Darkness Charming. She called him James Dean Lite. I called her Not My Therapist Anymore.