The Million-Dollar Wound (28 page)

He nodded and looked around furtively and opened a desk drawer and got out a sack.

“Two gee’s?” he whispered, holding on to the thing with both hands.

“Two gee’s,” I whispered back. “In cash. You’ll have the dough tomorrow.”

“I better,” he said, with his usual hound-dog expression, and handed me the sack.

I took it and walked down the stairs, out of Town Hall Station, in front of which the pretty, petite Mrs. Nick Circella was talking to Hal Davis and some other reporters, halfheartedly shielding her face with a gloved hand whenever a flashbulb went off.

I tucked Estelle Carey’s diary under my arm and walked by them.

That night I met Sally backstage at the Brown Derby at half past one; she stepped out of her dressing room wearing a white sweater and black slacks and a black fur coat and a white turban and looked like a million. Not Nicky Dean’s hidden million, maybe, but a treasure just the same.

“How can you look so chipper?” I asked her. “You just did four shows.”

She touched my cheek with a gentle hand, the nails of which were long and red and shiny. “I get a little sleep at night,” she said. “

You

ought to try it.”

“I hear it’s the latest rage,” I said.

She looped her arm in mine and we walked to the stage door. “It’ll get better for you. Wait and see.”

We’d spent Tuesday night together, in my Murphy bed, so she knew all about my sleeping trouble. She knew I would toss and turn, and then finally drop off only to quickly wake up in a cold sweat.

“I go back there when I sleep,” I told her. We were walking out on Monroe. It was cold, but not bitterly cold.

“Back there..?”

“To the Island.”

Our feet made flat, crunching sounds on the snowy sidewalk.

“Did you talk to your doctors about this?”

“Not really. I ducked the issue. I wanted to get home. I figured it would let up, once I did.”

She squeezed my arm. “Give it time. This is only your fourth day back. Say. Why don’t you see if a change of scenery helps your sleep habits? I’ve got a room at the Drake, you know.”

I grinned at her. “Surely not that plush white penthouse that fairy friend of yours sublet you, way back when.”

She laughed, sadly. “No. I don’t know what became of him, or his penthouse. It’s just a room. With a bed.”

“You talked me into it.”

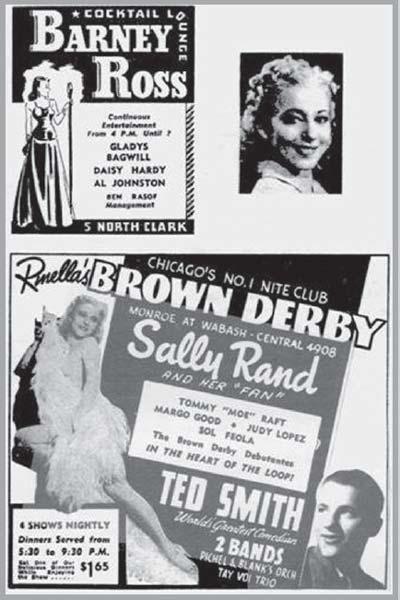

We crossed Clark Street, heading for the Barney Ross Cocktail Lounge. Traffic was light for a Friday night. Of course, the bars had already been closed for forty minutes.

“Do you know what this is about?” she asked.

I shook my head no. “All I know is Ben asked me to stop by, after hours tonight. I asked him if I could bring my best girl and he said sure, and drinks would be on the house, and we’d have the place practically to ourselves.”

“Are you

positive

that’s what he said?” she asked.

We were approaching the entrance, from which came the muffled but distinct sounds of music, laughter, and loud conversation. The door was locked, but through the glass a swarm of beer-swilling people could be seen. We stood there basking in the glow of the blue neon that spelled out Barney’s name and the outline of boxing gloves, wondering what was going on, and finally Ben’s face appeared in the glass of the door, and he grinned like a kid looking in a Christmas window, unlocked it, and we stepped inside.

“What’s up?” I asked him, working to be heard above the din.

“Come on back!” Ben said, still grinning, waving a hand in a “follow me” manner, leading us through the jam-packed, smoky saloon. The jukebox was blaring “Blues in the Night”…

mah mama done tole me…

and the place was filled with guys from the West Side, older ones my age or better, except for some kids in uniform, and a lot of ’em patted me on the back and grinned and toasted me as we wound through ’em,

way to go Nate, you showed them yellow bastards, Heller,

that sort of thing. The rest seemed to be people from the sports world, the fight game especially, including Winch and Pian, Barney’s old managers, who I glimpsed standing across the room talking to a young kid who looked like a fighter. I hoped for his and their sake he had a punctured eardrum or flat feet or something, or he wouldn’t have much of a ring career ahead of him, not in the near future anyway. A few reporters were present, mostly sports guys, but Hal Davis was there, and he had a bruise on his jaw that looked kind of nasty. The look he gave me was nastier than the bruise.

We ended up at the farthest back booth, around which the crowd seemed thickest, and Ben called, “Step aside, step aside,”

when I was in knee pants,

and they did, and I’ll be damned if a gray-haired version of Barney Ross wasn’t sitting there.

He looked at me with those same goddamn puppy-dog eyes in the same old bulldog puss, only his face was less full than it used to be. Like mine. He didn’t seem to have my dark circles under the eyes, though; but his once dark hair, which when last I saw him was salt-and-pepper, was now stone gray. He was sitting next to Cathy, the brunette showgirl he got hitched to at San Diego, but immediately slid out on seeing me, leaning on a native-carved cane he’d brought back from the Island, and stood and looked at me.

“You got old,” he said, smiling.

“You’re the one with the gray hair.”

The music was still loud,

who make you to sing the bloooes,

but we weren’t yelling over it. We could understand each other.

“You’re gettin’ there yourself,” he said, pointing to the white around my ears. Then he pointed to his own head of gray hair. “Turned this way that night in the shell hole, just like my pa’s did in the Russian pogroms.”

“Christ,” I said, getting a good look at his uniform. “You’re a fucking sergeant!”

His grin drifted to one side of his face. “I see they promoted you, too.”

“Yeah,” I said. “Back to civilian.”

His smile turned lopsided, sad. “Shouldn’t have got you into it, should I, Nate?”

Blues in the night…

“Shut up, schmuck,” I said, and he hugged me and I hugged him back.

“Sally!” he said, to the little vision in black and white standing next to me and looking on benignly at this sorry display of sentimentality. “It’s great to see you, kid!” He hugged her next, and I bet that was more fun than hugging me. “It’s good to see you two back together again.”

“Easy,” I said. “We’re just friends.”

“Yeah, sure,” he said. “Come on, slide in and sit with us!”

A couple of sportswriters had been sitting across from Barney and Cathy, in the booth, and they made way for us, thanking Barney, slipping their notebooks into their pockets. But Sally didn’t join us—Nat Gross, the “town tattler” on the

Herald-American,

stole her away; Sally smiled and shrugged, handed me her fur coat, said “Publicity’s publicity,” and was soon lost in the smoky throng.

“Reporters,” Barney said, shaking his head. “Take those sports guys, for instance. They wanted to know all about me bein’ voted boxing’s ‘man of the year,’ which is a crazy stupid thing anyway. I ain’t been in the ring since ’38! It’s supposed to be for the man who did the most for boxing last year, and they give it to

me.

What for?”

“Beats me,” I said. Cathy was beaming at him; they were holding hands. “When d’you get back? Why didn’t you tell me you were coming?”

“My furlough came through early,” he said, shrugging. “I was in New York, getting that ‘man of the year’ deal, and got a chance last night to hop a military flight here. I called Ben before I left to ask him to round some people up. It was his idea to surprise everybody. Anyway, I got in this afternoon, and spent the evening with Ma and the family. Tomorrow there’s going to be a reception with Mayor Kelly and the hometown fans and all; but tonight I just wanted to see my old pals. Damn, it’s great to be home!”

“I saw that stupid picture of you,” I said, smirking, shaking my head, “kissing the ground when you got off the hospital ship at San Diego. Some guys’ll do anything to get in the papers.”

He smiled back at me tightly and waggled a finger at me. “I swore if I ever got back home, my first act would be to stoop and kiss the ground. Remember?”

“I remember.”

“And I keep my promises.”

“You always have, Barney. So promise me you aren’t going back over there.”

“That’s an easy one to keep. I won’t be going back, Nate. I got an arm and leg loaded with shrapnel. It’ll be months before I can get around without my trusty voodoo stick.”

He was referring to his carved native cane, leaned up against the side of the booth next to him. The big head of the cane was a face with mirrorlike stones for eyes. In the mouth were what seemed to be six human teeth.

“Genuine Jap teeth,” Barney said, proudly, noticing me noticing them.

“Good, Barney,” I said. “It’s nice to know you didn’t go Asiatic or anything over there.”

Cathy spoke up. “Barney’s been transferred to the Navy’s Industrial Incentive Division.”

“That doesn’t have anything to do with social disease, does it?” I asked him.

He made a face. “Are you nuts?”

“Yeah, but don’t knock it—it got me out of the service.” I explained briefly about Eliot’s VD-busting role, and how he’d tried to hide behind governmental gobbledygook telling me about it. Barney got a laugh out of that.

“They’re gonna send me touring war plants,” he shrugged, seeming embarrassed, “telling the workers how the weapons and stuff they’re making are helping us lick the Japs. Fat duty. Pretty chickenshit, really.”

Cathy looked pointedly, first at him, then at me, and said. “Don’t listen to him. The brass told him this was important duty, just as important in its way as Guadalcanal. There’s a serious absenteeism at some war plants, and a half-time talk from a hero like my husband can really get those workers off their rears and breaking their necks to beat production schedules!”

She was as full of energy as all three Andrews Sisters, but there was something wrong behind all that pep. Something a little desperate. I didn’t know her very well—I’d figured Barney marrying a showgirl was trouble, him being on the rebound from Pearl, his first wife, who I’d liked very much. So I’d resented Cathy, I guess, and never really gave her a chance.

But I could see, tonight, in this smoky gin mill, she really loved the mug. I could also see something was deeply bothering her, where he was concerned.

Barney looked at her, movie-star pretty with her perfect pageboy and smart little blue dress, and it was clear he loved her too. “Cathy’s turned down two movie roles, Nate, just so she can travel around with me. This war-plant tour’s going to mean hitting five, six, sometimes seven plants a day. And we’ll be doing War-Bond rallies and blood-bank drives… I don’t mind, of course—we both know how the boys are suffering in those jungle islands, how bad they need guns and ammo.”

He’d do fine on the “Buy Bonds” circuit.

I said, “How long will you be in town, Barney?”

“It’s an extended furlough. At least a month. And this’ll be our home base, after we start the tour.” He smiled at Cathy and squeezed her hand. She had on an aluminum bracelet he’d given her fashioned from a section of a Jap Zero.

I said, “Remember D’Angelo? He’s here in town.”

Barney’s smile disappeared. “I know. I had Ben invite him here tonight, but he didn’t show.”

“He lost a leg, you know.”

“He’s one up on Watkins,” Barney said. “He lost both of his.”

“Damn. Where is he?”

“San Diego. I stopped in on him. Still in the hospital, but he’s doing pretty good.”

“I want his address.”

“Sure. Those two Army boys pulled through okay; I’ve got their addresses, too, if you want ’em.”

“You wouldn’t know if Monawk had any family, would you?”

He shook his head; his expression was morose. “I checked. No immediate family, anyway.”

I just sat there. The Mills Brothers were singing “Paper Doll” on the jukebox now, which somebody seemed to have turned down.