The Million-Dollar Wound (32 page)

Conversation had woken me; and muffled conversation was still quite audible, even though I was sitting on the couch and the door to the living room was across the study from me. Occasionally the pitch of the conversation peaked—in anger? One of those peaks had been loud enough to wake me, anyway.

I got up. Slipped out of my shoes. Crept across the study to the door. I didn’t dare crack it open. But I did dare place my ear up to it.

“Frank,” a harsh voice was saying, “you brought Browne and Bioff to us. You masterminded this whole thing—and it went sour.”

“You didn’t complain at the time, Paul.”

Paul?

Jesus Christ—Paul Ricca. The Waiter. The number-two man. Capone had his Nitti; and Nitti had his Ricca.

And I didn’t have a gun.

“There is no point in all of us going down,” Ricca said. “Remember how Al took the fall for us, and went on trial alone? Well, that’s the way we ought to do it now.”

“It ain’t the same situation, Paul.” Nitti’s voice was recognizably his; but something was different. Something had changed.

The strength was gone.

“Frank,” Ricca said, “you can plead guilty and we’ll take care of things till you get out.”

Right. Like Nitti took care of things for Capone.

“This is not that kind of case,” Nitti said, voice firmer now. “This is a conspiracy indictment. Nobody can take the fall for the rest of us in this one. We all have to stick together and try to beat it.”

Ricca began swearing in Sicilian; so did Nitti. And it began to build. Other voices, in English, in Sicilian, were trying to settle the two of them down. I thought I heard Campagna.

I knelt down. Looked through the keyhole. Just like a divorce case.

I could get a glimpse of them, sitting around the living room in their brown suits, just a bunch of businessmen talking—only among them were Frank Nitti, Paul Ricca, Louis Campagna, Ralph Capone and others whose faces I couldn’t see, but, if I could, whose names would no doubt chill me equally to the bone.

Ricca, a thin pockmarked man with high cheekbones, was pale, panting. He pointed at Nitti, as they stood facing each other, Ricca much taller than the little barber.

“Frank, you’re asking for it.”

Five simple words.

Dead silence followed. Nitti was looking to the other men, to their faces. It seemed to me, from my limited vantage point, that all save Campagna were avoiding his eyes. And even Louie wasn’t speaking up for him.

The lack of support meant one thing: Ricca had deposed Nitti. And without the intricate, dangerous chesslike moves Nitti had used to maneuver Capone off the throne and into the pen. Ricca had, through strength of character alone, through sheer will, toppled Nitti.

And Nitti knew it.

He walked toward the front door.

I couldn’t see it, but I could hear it: he opened that door. Cold March air made itself heard.

He walked into my keyhole view again.

And, his back to me, gestured toward the outside.

The men looked at each other, slowly, and rose.

I moved away from the door and went back to the couch and sat, trembling. I knew what this meant. Nitti’s wordless invitation for his guests to leave was a breach of the Sicilian peasant rules of hospitality they’d all been reared under. It was his way of turning his back on them. It was his way of expressing contempt. Defying them. Ricca, especially.

And Ricca’s words—

Frank, you’re asking for it

—were a virtual death sentence.

I could hear them out there, shuffling around, getting on their coats and hats, no one saying anything.

Although, finally, when they all seemed to be gone, I thought I heard Campagna’s voice. Saying simply, “Frank…”

Clearly, I heard Nitti, who must’ve been standing just outside the study door, say, “Good night, Louie.”

I slipped my shoes back on, stretched out on the couch and closed my eyes. Wondering if I’d ever open them again.

The light above me went on; light glowed redly through my lids. I “slept” on.

A hand gently shook my shoulder.

“Heller,” Nitti said, softly. “Heller, wake up.”

I sat slowly up, sort of groaning, rubbing my face with the heel of a hand, saying, “Excuse me, Frank—oh, hell. Aw. I don’t know what happened. Must’ve dozed off.”

“I know you did. I was out for a walk, and I got back and you were sound asleep. Snoring away. I couldn’t bring myself to wake you. So I just let you sleep.”

He sat next to me. He looked very old; very skinny; very tired. Cheeks almost sunken. His dark eyes didn’t have their usual hardness. His hair was the real tip-off, though: the little barber needed a haircut.

“I didn’t see the harm,” he said, “letting you sleep. Then, to be honest with you, I forgot all about ya.” He gestured out toward the other room. “I had some business come up all of a sudden, and I sent my wife and boy over to the Rongas, and she said now don’t forget about Heller, and I went and forgot about you, anyway.” He laughed. For a man who minutes ago had heard his own death sentence, and who had in return thrown down the gauntlet to Ricca and the whole goddamn Outfit, he was spookily calm.

“When I first got back from overseas,” I said, “I had trouble sleeping. But lately I catch myself napping every time I turn around. I’m really sorry.”

He waved that off. He looked at me; his eyes narrowed—in concern? Or was that suspicion?

“I hope my business meeting didn’t disturb your sleep,” he said.

“Nope,” I said, cheerfully. I hoped not too transparently cheerfully. “Slept right through it.”

“Why was it you wanted to talk to me, Heller?”

“Uh,

you

invited

me

here, Frank.”

“Oh. Yeah. Correa called you. That prick.”

“He’s going to call me to testify. I guess they were keeping tabs on you, when we were having our various meetings over the years. They’re going to ask about those meetings, and…”

He shrugged. “Forget it.”

“Well, that’s what I intend to do. What you and I talked about is nobody’s business but ours. Like I told Campagna, I got some convenient after-effects of my combat duty—they treated me for amnesia, while I was in the bughouse. I don’t remember nothing, Frank.”

He patted my shoulder. “I’m proud of what you did over there.”

“What?”

“I brag on you to my boy, all the time. You were a hero.” He got up and crossed to an expensive, possibly antique cabinet and took out a bottle of wine and poured himself a glass. “This is a great country. Worth fighting for. An immigrant like me can have a home and a family and a business. Some vino, kid?”

“No thanks, Frank.”

He drank the wine, pacing slowly around the little study. “I never worried about you, kid. You coulda gone running off the mouth about Cermak, and you didn’t. You coulda done the same thing where Dillinger was concerned, but you didn’t. You understand it,

omerta,

and you ain’t even one of us.”

“Frank, I’m not going to betray you.”

He sat down next to me. “You seen Ness lately?”

“Yeah,” I said. “Last month.”

“You know what he’s doing these days?”

“Yeah,” I said, and smiled.

Nitti sat there and laughed.

“Al coulda used his help,” he said, and laughed some more.

When he stopped laughing, he finished the glass of wine and said, “That’s another secret you kept.”

“Frank?”

“You knew about O’Hare.”

I swallowed. “You mean, you knew…”

“That you figured out I…” He gestured with one hand, as if sculpting something. “…sent Al away. Yeah. I saw it in your eyes, kid, when we talked that time.”

He meant that night in ’39 in the suite at the Bismarck.

“Then why in hell am I alive?” I said.

“I told you to stay out of my business. You stayed out, more or less. I trust you. I respect you.”

“Frank—I’m right in thinking you didn’t have anything to do with Estelle Carey’s death, aren’t I?”

“Would I invite such heat?” His face tightened into an angry mask. “My bloodthirsty friend Paul the Waiter sent those”—and then he said something in Sicilian that sounded very vile indeed—“to hit her. He was afraid she’d talk, this grand jury thing. I believe her killers took it on themselves to try to make her talk.” He laughed without humor. “To make her lead them to money she never had.”

“Money she…what?”

He got up and poured himself some more wine. “The Carey dame never had Nicky’s dough. He didn’t trust her. He thought she’d fingered him to the feds. That million of his, well, it’s really just under a million, the feds exaggerate, so they can tax you more…anyway, that million is stashed away for Nicky when he gets out. He’s being a pretty good boy. He’s talked some, but not given ’em anything they didn’t already have. Willie and Browne, well…don’t invest in

their

stock.”

Nitti’s openness was startling. And frightening. Was he drunk? Was he telling me things he’d regret telling me, later?

“You killing that bastard Borgia and his bitch was a good thing,” he said. “And then calling me so we could clean up, that I also appreciate. Think of what the papers woulda done with that; talk about stirring up the heat. Do you know how many of the boys have been pulled in over the Carey dame? Shit. That’s Ricca for you. Anyway.” He sipped his wine. “I owe you one.”

He’d said that to me before, more than once. More than twice.

“Hey, you have some wine, now,” he said.

I had some wine. We sat and drank it and I said, “If you feel you owe me one, Frank, I’d like to collect.”

Nitti shrugged. “Sure. Why not.”

“You know about my friend Barney Ross.”

He nodded. Of course he knew; I’d heard it from him. Or from Campagna. Same difference—before tonight, at least.

He said, “Have you talked to him about this problem of his?”

“Yes I have,” I said. “And he claims he can handle the stuff. He needs it for his pain, he says. To help him sleep. He acted like it was no big deal—then made me promise not to tell his wife, his family.”

“He’s a good man,” Nitti said. “He shouldn’t have this monkey on his back. It will ruin him.”

“I know.”

It seemed to anger Nitti. “He’s a hero. Kids look up to him. He shouldn’t go down that road.”

“Then help me stop him.”

He looked at me; the old Nitti seemed to be home, if only briefly, in the hard eyes.

“Put the word out,” I said. “Nobody in Chicago sells dope to Barney Ross. Cut off his supply.

Capeesh?”

“Capeesh,”

Nitti said.

We shook hands at the front door and I walked out into the wintry air, wondering how many eyes other than Nitti’s were on me.

Drury drove. We left his unmarked car on Cermak Road, near Woodlawn Cemetery, and walked along the railroad tracks, south. A light drizzling rain was falling. These were Illinois Central tracks, freight, not commuter; at this time of afternoon, just a little before four, there would be little or no train traffic, not till after rush hour—Cermak Road was too major a thoroughfare to be held up by a train, this time of day.

We were out in the boonies, really. To my left a few blocks was downtown Berwyn, but just due north was a working farm; and right here, the tracks ran through a virtual prairie—tall grass, scrub brush and trees. Up at right was a wire fence, behind which loomed the several faded brick buildings of a sanitarium. Some uniformed cops were gathered there; three men in coveralls, railroad workers obviously, were being questioned over to one side.

I followed Drury down the gentle embankment from the tracks through brush and tall grass to where the cops stood by the wire fence. One of the cops, a man in his fifties, in a white cap, walked to Drury and extended a hand and the men shook, as the white-capped cop said, “Chief Rose, of the Riverside P. D. You’d be Captain Drury.”

Drury said he was.

“Thanks for getting out here so quickly. We need you to positively ID the body. And we could use a little advice about where to go from here…”

Drury didn’t introduce me; everybody just assumed I was another cop. This time I’d been in

his

office, when he got the call. Correa had asked him to talk to me again, and as a courtesy I’d taken the El over to Town Hall Station. I was sitting there being scolded by him when his phone rang.

Now here we were, in a ditch next to an IC spur between North Riverside and Berwyn, in the midst of a bunch of confused suburban cops who’d drawn a stiff who was just a little out of their league—although very much a resident of their neck of the woods.

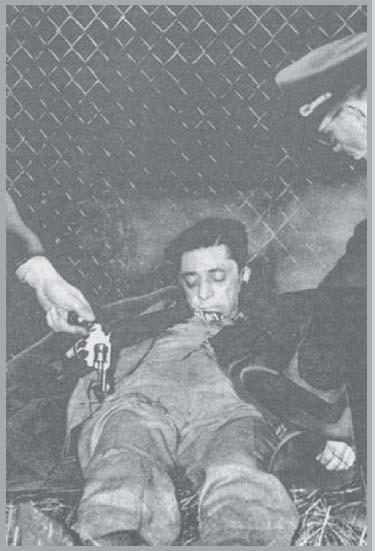

He sat slumped against the fence, parting the tall grass around him, brown fedora askew on his head, which rested back against a steel post, eyes shut, a revolver in his right hand—a little black .32, it looked like—and wearing a snappy gray checked suit, expensive brown plaid overcoat, blue and maroon silk scarf. On his shoes were rubbers; some snow was still on the ground, after all. Above his shoes stretched the off-white of long woolen underwear. Behind his right ear was a bullet hole; above his left ear was the exit wound.

Both Drury and I bent over him, one on either side of him. The smell of cordite was in the air.

“He must’ve got his hair cut this morning,” I said.

“Why do you say that?” Drury asked.

I hadn’t told Drury that just yesterday I’d seen this man. And I wasn’t about to.

“Just looks freshly cut, that’s all. You can smell the pomade.”

“I can smell the wine. He must’ve been dead drunk. Well, now he’s just dead.”