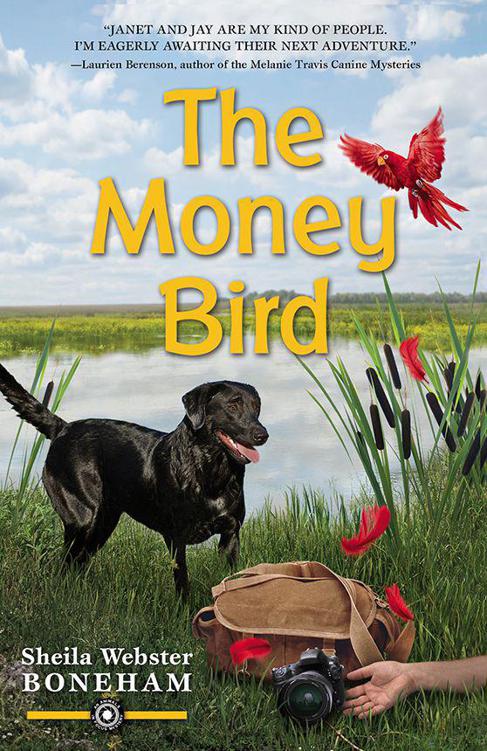

The Money Bird (An Animals in Focus Mystery)

Read The Money Bird (An Animals in Focus Mystery) Online

Authors: Sheila Webster Boneham

Tags: #Fiction, #mystery, #cozy, #mystery novel, #mystery fiction, #novel, #animals, #soft-boiled, #dog show, #dogs

Copyright Information

The Money Bird

© 2013

Sheila Webster Boneham

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any matter whatsoever, including Internet usage, without written permission from Midnight Ink, except in the form of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

As the purchaser of this ebook, you are granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. The text may not be otherwise reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, or recorded on any other storage device in any form or by any means.

Any unauthorized usage of the text without express written permission of the publisher is a violation of the author’s copyright and is illegal and punishable by law.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

First e-book edition © 2013

E-book ISBN: 978-0-73873801-7

Cover illustration by Joe and Kathy Heiner/Lindgren & Smith

Cover image: Black labrador retriever: iStockphoto.com/David Gomez

Cover design by Lisa Novak

Midnight Ink is an imprint of Llewellyn Worldwide Ltd.

Midnight Ink does not participate in, endorse, or have any authority or responsibility concerning private business arrangements between our authors and the public.

Any Internet references contained in this work are current at publication time, but the publisher cannot guarantee that a specific reference will continue or be maintained. Please refer to the publisher’s website for links to current author websites.

Midnight Ink

Llewellyn Worldwide Ltd.

2143 Wooddale Drive

Woodbury, MN 55125

www.midnightink.com

Manufactured in the United States of America

For the retrievers who have brightened my life and my home:

Labrador Retrievers Raja, Annie, and Lily,

and Golden Retriever Sunny

author note

This is a work of fiction, so I have taken the liberty of creating a fictional bird, the Carmine Parrot, to represent the many species that suffer individually and as whole populations from wildlife trafficking and habitat destruction. The examples of smuggling mentioned in

The Money Bird

—tiny birds packed into curlers, primate infants carried under clothing, birds and other animals stuffed into boxes under floorboards and seats—are all too real and horrifying. So too is the worldwide slaughter of animals for their parts, which are used for everything from fur coats to traditional medicines to hair clips, jewelry, and decorative items. To learn more, I suggest you start with http://worldwildlife.org/threats/illegal-wildlife-trade, or contact the World Wildlife Fund, 1250 24th Street NW, Washington, DC 20037, (202) 293-4800.

money bird

: the last bird the dog retrieves in a retriever field trial; without this bird, the dog and handler win no money.

one

The man with the

gun stood half hidden in chest-high brush to

the

west of Twisted Lake. Drake crouched a hundred yards to the east,

gaze fixed, muscles twitching. The only thing obstructing my view of either was the cloud of no-see-ums whirling around my head. Daylight was dying, and the eastern bank of the lake was already lost in shadows, so I knew I wouldn’t see clearly for much longer. The breeze had all but died in the last half hour and the bright scent of day bowed to darker notes of mud and rot.

The man, Collin Lahmeyer, tucked the 12-gauge under his right arm and picked up an orange canvas-covered training bumper with the other. He let it drop from his fist and bounce at the end of a half yard of thin nylon cord, then swung his arm and let fly toward a small island fifty yards offshore. Drake quivered as he watched. He shifted one foot forward an inch but held his ground when his partner, Tom, murmured, “Wait.”

The cylindrical bumper stalled high in the air, vivid as blood against a bank of charcoal clouds. Drake tracked the object, his focus so tight that he didn’t so much as twitch when the shotgun’s long barrels rose and the gunman shouldered the weapon. A single blast cracked the August dusk and made my eyes blink and my shoulders tighten. I’ve been photographing field dogs in training and competition for years and I knew the shells were blanks, but every blast still somehow caught my reflexes by surprise.

The training bumper plummeted into a tangle of goldenrod, thistle, and bindweed. Tom whispered one magic word—“Fetch!”—and Drake was gone from his side. The big dog leapt from the bank at a full-out run and was swimming before he hit water. His shoulders muscled through the light chop and his thick tail worked like a rudder to keep his heading true. He swam to the island, charged from the lake in a glittering spray, and disappeared into dense brush. Fading blossoms of ironweed jostled one another, mapping his progress. He quartered for five or six seconds, moving back and forth through the brush, searching. The wild swaying of the plants stopped, signaling that he’d found the bumper, then resumed as Drake turned back toward the lake.

The gunner, Collin Lahmeyer, had a better view of the dog than did Tom, his owner and handler. I had the best view of all. I’m Janet MacPhail, professional photographer and lifelong cynophile. I’d been shooting the Northern Indiana Hunting Retriever Club’s practice session since late afternoon, hoping to capture some of those beautiful dogs in photos I could sell to publishers and, often, to the dogs’ proud owners. I peered through my viewfinder, up to my muck-smeared elbows in ragweed and burdock. I didn’t expect to get a decent shot against the dark water and smoldering horizon, but the zoom let me follow what my naked eye would never pick up.

Collin gave a thumbs-up, indicating that Drake had his “bird,” the foam-filled canvas bumper, and called, “There’s your money bird!” In a field trial, the money bird is the last bird the winning dog retrieves, the one that brings home the cash prize. There was no cash here, and the bird was made of batting and canvas, but Tom Saunders looked like he might pop his buttons, if there’d been any on his faded U of Michigan sweatshirt. Tom and I had started seeing each other back in May, but we’d had only a couple of weeks before he and Drake headed off for a summer of fieldwork in New Mexico. Tom is an ethnobotanist. He teaches in the anthropology department at the local campus, but he likes to run off to exotic places to do research between terms. We’d developed quite an electronic relationship over the summer, and although I declined all invitations to head west for a visit, I had to admit that I was both thrilled and terrified to have him back in town. As I stood watching the man work with his dog in the sultry dusk, the Janet demon in my head whispered

time to jump his bones

. Good Janet pointed out that poor proper Collin Lahmeyer might never recover from the spectacle, and besides, the ground was soggy and the mosquitoes ravenous. Romance could wait.

I knew that Drake needed only one more qualifying run to complete his MH, his Master Hunter title, and the way this training session was going, he looked ready to me. Not that I know much about training retrievers that I haven’t gleaned from listening to friends involved in the sport. I have an Australian Shepherd myself, and we pursue other sports. I knew, though, that Drake had been entered in a Hunt Test the end of May and should have finished his Master Hunter title there, but he pulled a shoulder muscle two days before the event. Several people advised Tom to give the dog painkillers and run him anyway, and, gutsy Labrador Retriever that he was, Drake would have worked through the pain if his beloved Tom asked him to. Tom refused—another feather in the cap he wore in my viewfinder. Now, after two months of R and R in the high desert, the dog appeared to be back on top of his game.

I glanced at Tom. He was

talking to a man I didn’t know

while

watching for Drake to reappear from the brush. I looked through my viewfinder again. Drake burst from the brush and was almost back to the water when he veered away from the lake, back toward the west side of the island. The cover there was lower and more sparse than where the bumper went down, but I still couldn’t see what he was after. He was quite a sight, though, his wet coat sparkling in the low-angled light.

“That’s not like him,” said Tom, blowing one long, shrill blast on his whistle. Drake looked over his shoulder, his glossy black coat set off by the orange bumper in his mouth and the black-eyed Susans scattered behind him. I clicked off several more shots.

Click click click.

Drake held for a pair of heartbeats, then went back to what he

was doing. Whatever it was, it was strictly against orders. Tom blasted

the whistle again. I glanced at him, and noticed the stranger walking back toward the road, where we had all parked.

The dog turned around and made for the water. I could no longer see the orange bumper, but he had something in his mouth. The water around him fanned into a gilded wake as he swam.

Click click

. As he came closer, a strip of orange canvas showed in his grip, but most of the bumper was obscured by something else. I tightened my focus and zoomed in on his face, but I couldn’t tell what it was. Fabric?

Drake exploded onto the bank, set his burden on the grass, and shook a thousand water diamonds into flight. I clicked off a few more shots. Drake picked up the bumper and his other find, climbed the low bank, and sat six inches in front of Tom, sweeping the grass with his tail and offering up the bumper and what appeared to be a canvas bag. I swung the camera their way.

Tom reached to take Drake’s gifts, his face aglow with love and

pride. But the look was fleeting. The muscles around his eyes and

jaw tightened, waking a butterfly of fear in my own chest as I wondered what had put that look on Tom’s face. I zoomed in tight on Drake’s head and sucked in a breath as I saw what Tom had seen.

An erratic crimson trickle wound through the silvered hair of Drake’s lower jaw and fell, drop by drop, onto the darkening ground.

two

Tom set the bumper

and the bag on a boulder, wiped the blood off Drake’s face with the hem of his sweatshirt, and checked Drake’s mouth, inside and out.

“He seems to be fine. Maybe just jabbed himself on something. I don’t see any more blood,” said Tom, standing up and wiping his hand on his jeans.

Drake stepped toward the canvas bag, nose working, and Tom told him to settle. The dog lay down sphinx-style in the grass, nostrils twitching, neck stretched toward the sodden object on the big rock.

The bag was about ten by fifteen inches with a half-open zipper along one long side. It showed signs of having once been white or beige, but the bottom third was stained dark and a trail of chartreuse duck weed angled across the fabric. A shoulder strap dangled from one corner. The other end had torn free and was fringed with stray threads. Water drained from its corners, arced along the curve of the boulder, and dripped onto the clay below.

Tom lifted the bag and turned it over and back. There was nothing

distinctive about it. No writing, no logo. Tom pulled the zipper open

, gave the bag a couple of shakes to throw off the bulk of the water,

and peered inside. “Oh my God! Yuck!” He tried to pull the bag away, but I grabbed his hand and peered in. Tom burst out laughing and elbowed me. “Go

tcha!”

“Funny.” I elbowed him back as I pulled the bag closer and looked inside. “What’s that?” Something lay along the bottom seam. In the fading light it looked a bit like a fish bone, whitish against the rust-tinted base of the bag and thicker at one end than the other, but I doubted there were any fish with bones that big in Twisted Lake.

Collin stepped toward Tom. “What is it?” he asked, fishing around in his pocket for something.

Tom glanced at Collin, then at me. “Looks like a feather.”

“A feather?” Collin and I harmonized.

The soaked barbs were flattened against the quill and hard to make out against the stained fabric, but I could see that Tom was right. It was hard to say what color it was, but at eight or nine inches long, it came from a fairly big bird. “Weird.” I gestured toward the dark stain on the bag’s lower portion. “What do you think that stain is?”

“There’s something else,” Tom said. “Looks like money.”

“Money?” Collin and I were starting to sound like parrots.

“Yeah. Well, a piece of money. Looks like a corner torn from a bill. There are two zeroes, so I think that makes it part of a C-note.” Tom started to reach into the bag, but I caught his arm.

“Maybe we should call someone.”

Both men looked at me. One blurted, “Why?” and the other, “Who?”

I wasn’t sure myself, but the last time I picked up an abandoned bag and removed its contents, it turned out to be evidence in a murder case and I spent some very uncomfortable moments explaining my actions to the police. I looked into Tom’s eyes and said, “Think about it. That little island isn’t exactly on a walking path. You wouldn’t get there by accident. And besides, this is private property, so why was anyone with a bag of feathers and money here in the first place?”

Tom peered into the bag again. “It’s not exactly a ‘bag of feathers and money.’”

He must have felt the sticky warm air temperature rise yet higher, because he looked at me and backpedaled. “You’re right, though, it is an odd place for anyone to be who doesn’t belong. But you could probably wade to the island from where Collin threw the bumper.”

“You need a boat. Or you could swim,” said Collin. “There’s a drop off there. My father-in-law used to keep a diving raft out there. Safest place for kids to go in head first.”

We stood in silence and stared at the bag for a bit, until Drake yawned loudly and snapped us out of it.

“I’ll call Jo and see what she thinks we should do.” Detective Jo Stevens was the lead investigator when three members of our local dog-training community were murdered six months earlier. After a nerve-wracking start involving that other found bag, Jo and I had become friends. She’d know what to do.

Collin pulled a plastic bag from the stock of poop bags in his pocket and held the open end toward Tom. “This’ll keep your car clean.”

Tom folded the canvas a couple of times and slid it into the bag Collin held open. The water dripping from the fabric settled into the bottom crease of the plastic and I watched as it took on a distinctly pink cast. “That’s odd.”

Collin leaned in for a closer look.

All three of us watched the puddle forming under the canvas turn ever pinker, and I stared into Tom’s bluebird-blue eyes and said, “It’s blood.”

“Maybe from Drake’s mouth?” asked Collin, looking at the dog.

“It took a lot of blood to make a stain like that,” I gestured toward the bag, “and to survive the swim. If it is blood, maybe what we saw on Drake came from the bag.”

Both men insisted that it couldn’t be blood and I was about to argue when something, more feeling than sound, made me look across the water. Drake, his sharp gaze also directed toward the island, moved up against my knee and let out a soft, un-Drake-like grumble. I scanned the vegetation beyond the faraway shoreline through my viewfinder, zooming and sharpening shrub by shrub. “There’s someone out there.”

Collin and Tom followed my gaze. Nothing for half a minute, and

then a dozen hollering crows exploded from the island’s single tree,

a ghost-pale old sycamore. I turned to Tom and heard myself say,

“Murder.”

three

Tom froze, no doubt

hoping he had heard wrong.

“What did you say?” Collin asked.

I snapped the cap onto my lens and tried to fend off the shadow beginning to spread through my mind. “Crows. A murder of crows.”

Be a good name for a group of humans,

I thought, as I smacked a humongous mosquito and peeled her corpse off the sticky veneer of bug juice and sweat on my arm.

We walked toward the road without speaking, all three of us swatting at my deceased tormentor’s gluttonous relatives. Drake trotted close to Tom’s left knee, tail waving and tongue dripping. I envied the men’s long legs as I clambered down and through the drainage ditch that parallels the road and then fought my way through face-high weeds on the upward slope to the road.

Tom looped the bumper’s nylon line through the wires of Drake’s crate and tied it loosely, letting the canvas-and-batting cylinder hang to dry. He tossed the plastic bag into a corner of the van bed. “Up ya go,” he told Drake, and the dog hopped into his crate and turned, tail thumping in anticipation. Tom emptied a sandwich bag of premium grain-free kibble into a stainless steel bowl and set it in the crate. He twisted the top from a beat-up water bottle, emptied half into the water bowl in Drake’s crate, and leaned back against the van’s bumper while Drake, in typical Labrador style, inhaled his dinner. “Drink?” Tom waggled the bottle at me, and swigged it empty when I declined.

We had parked on Tappen Road, a narrow gravel lane off Cedar Canyons Road north of Fort Wayne. Heron Acres, two hundred acres of lake, woodland, and uncultivated open ground, belonged to Collin Lahmeyer’s in-laws, who let Collin and his retriever group use the place for training. This was the group’s first time back since early June. Collin’s family takes up residence in the cottage at the far end of the lake for most of the summer, and between various grandkids and granddogs racing around the lake and grounds, it gets a bit congested for training. I’d been out a couple of times in June to photograph birds, but was always early enough to be long gone before summer fun started. It was a beautiful place, but across the road a crop of McMansions was springing up with alarming speed, and Tom feared it was just a matter of time before Heron Acres felt the weight of bulldozer treads.

To the west was another expanse of semi-wild ground owned by the Treasures on Earth Spiritual Renewal Center, brainchild of one Regis Moneypenny. Tom and I had speculated on whether it was the man’s real name and decided it wasn’t. Whoever he was, he had attracted a well-heeled congregation, or clientele, or whatever they called themselves. The collection of Lincolns, Beemers, Lexuses, Caddies, Mercedes, and one bright red Jag I had seen in the center’s landscaped lot attested to that.

One of the vehicles had apparently strayed onto Tappen Road by mistake. There was nothing but corn on one side and Guernsey cows on the other between where we stood and the dead end a half mile farther on, so no reason for anyone to drive down there unless they were lost. The curvaceous metal body crept toward us like a giant black beetle, the tinted windows watching like so many eyes. I expected one of them to open and reveal a human being in need of directions, but the sedan kept moving, barely, until it passed us. Then it slowly accelerated, making scuttling sounds in the gravel, headlights igniting as the car turned east onto Cedar Canyons Road.

We looked at each other and shrugged in unison. “Creepy,” I said.

Tom removed the empty bowl from Drake’s crate and shut the door.

“Our turn. Can I buy you some supper?” And darned if the man didn’t wink at me just as I turned away.

I suppressed the little tingle in my belly, walked to my van, and fished my cell phone from under a bag of desiccated liver in my tote bag. The number was ringing by the time I got back to Tom. He raised his eyebrows, and I answered his unspoken question. “Jo Stevens.”

When I finished the call, I shoved my cell phone into my pocket and said, “I need to get home. Jay’s been locked up since mid-afternoon.”

“So how ’bout I grab something on the way and meet you there?”

It was after eight and I hadn’t been planning to eat more than some fruit when I got home. Fruit surrounded by Edy’s ice cream. As usual, hunger and hormones won the day, or evening, and Tom and I set out separately for the same destination.

four

Jay met me at

the door. As I watched his bum wriggle and the light dance through his eyes, I remembered some know-it-all telling me at my last photo club meeting that bob-tailed dogs can’t express their emotions as well as their tailed brethren. I recommended she spend a few minutes with an Australian Shepherd and then get back to me. As if he’d read my mind, which I wouldn’t doubt for a nanosecond, Jay stood smack in front of me and bared his incisors in a goofy grin, his hips still doing the hula.

I shoved some magazines aside and set my camera case on the kitchen table. Then I straddled my dog, wrapped my arms around his neck, and smooched the silky top of his head. It’s not a maneuver I’d recommend except for dogs and people who absolutely trust one another, but we qualify. After a few seconds we disengaged and crossed the room. “Out we go,” I said, flipping the deadbolt and pulling the back door open. The sensor picked up Jay’s movement and lights came on in the backyard. I’d had several new ones installed, all triggered by motion detectors and backed up with batteries, after I was attacked by a gun-toting intruder last spring. Granted, it was hardly a case of random violence, and was unlikely ever to happen again, but the lights still made me feel safer. The lights, and the new touch-pad

locks that let me do away with the key under the geranium pot. And

my vow to always, always listen to my dog and cat if they ever acted weird again.

Jay stayed outside to patrol the yard and update his territorial notices. Back in the house, I looked around and was just gearing up for a tidying frenzy when my orange tabby, Leo, waltzed in and yawned at me, his long striped tail held high like a shepherd’s crook. He hopped onto the chair nearest me. I bent toward him and we bonked noses, feline for “Hi, where ya been?” and then I scooped him up, kissed him, and hugged his vibrating body, smooshing my face into his tawny fur.

I could stay like that, glued to one of my animals, for the rest of my life, but a pesky whisper in my brain kept hissing about the state of the house, so I put Leo back on the chair and began triage. Tom kept his place so tidy that I’d become a tad more conscious of my disinterest in housekeeping, at least when I knew he was coming over. First, to the bedroom with the pile of clean undies I had set on the kitchen table earlier to make room in the dryer for Jay’s bedding. I grabbed my running shoes from beside my own bed and my lime-green gardening clogs from in front of the open closet and was about to toss them in when my old book bag caught my eye. It hung from a plastic hanger, and its size and deep red hue sent my mind racing back to Twisted Lake. Who leaves a canvas bag containing a feather and torn money on someone else’s private island? More troubling, what could possibly stain the canvas that rusty red? Blood. I was sure of it, no matter what Tom and Collin thought. A lot of blood, I thought, to saturate the fabric enough to survive the swim back to the mainland in Drake’s grip, even if the canvas was waterproofed.

A car door slammed outside and brought me back to the task at hand. I tossed the shoes into the closet and slid the door shut. Then I snagged the half-empty diet root beer can from the nightstand, whirled down the hall to the bathroom, tore the used towels off the shower and towel rods, raced back to the bedroom, and dropped them into the hamper. I also dropped in the root beer can, dousing the towels with the remaining fluid and making me mutter something I was trying to expunge from my vocabulary. I retrieved the can and crumpled it in revenge, slammed the hamper lid, and hustled back to the linen closet across the hall from the bathroom door. As I hung a pair of nearly matching towels on the towel bars, I heard the front door open, followed by Tom’s, “Honey, we’re home.”

The scent of fried chicken and the bang-bang-bang of Drake’s tail against the wall lured me into the kitchen just as the back door flew open and Jay exploded into the room. The two dogs acknowledged each other with a quick sniff, but were more interested in the containers Tom set on the table. They positioned themselves shoulder to shoulder, noses twitching in the aroma that poured from the red-and-white bucket on the table.

Tom wrapped me in his arms and kissed me, one of those delicious kisses that could have gone on and on and morphed into something more serious, but a terrifying image of our two dogs choking on chicken bones while we were distracted broke the spell. Besides, the antihistamine I took before I went to the lake was long gone and the one I took when I got home hadn’t kicked in yet, so I pried my lips off Tom’s and gasped, “Can’t breathe.”

At the same instant, he said, “Chicken bones,” confirming that I am in serious trouble with this guy because we’re definitely on very similar wave lengths.

Drake was nearly dry, but still too damp for carpet or couch, so I pulled a baby gate out of the laundry room and barricaded all of us into the kitchen. Piles of reading matter on every horizontal surface aside, I do have my limits, and damp dogs do have to stay off the carpets and upholstery. I turned to get some plates from the cupboard and tripped over the dogs, who were jockeying for the best view of what lay beneath the lid Tom was peeling off the bucket.

“Okay, that’s it. Everybody out!” I pulled the door open and directed the two reluctant canines out to the backyard. Leo followed them. Tom tucked the bucket of chicken into the curve of his arm and grabbed the bag of sides. With his free hand he pulled two bottles of Killian’s Red from the fridge and scurried after the dogs, calling back over his shoulder, “Soup’s on!”

All I had to do was shut the door and follow.

five

Tom and I sank

into my Adirondack chairs with plates on our laps and the buckets of food on a side table between us. I’d bought the rusty old table at a garage sale a couple weeks earlier for a pittance and made it sing with tangerine spray paint. The bug lights by the back door cast an odd yellow glow over the yard and the three eucalyptus candles made it smell vaguely like vapor rub, but the neighborhood mosquitoes apparently found the atmosphere even more disturbing than I did and we weren’t eaten while we ate.

“Leo, my man.” Tom set his plate on the table, gathered the cat like a baby into the cradle of his arms, and gently massaged Leo’s chin and chest. The cat squinted at Tom, his amber eyes aglow in the candlelight. He

mrrowled

and accepted the snuggle for a third of a minute, then wriggled free, sauntered to where Tom had told the dogs to lie down, bonked noses with Jay and tolerated a sloppy

swipe of the dog’s tongue. Then he turned his attention to Drake. Leo

sniffed the Lab’s damp head and legs daintily, giving the impression that he didn’t want to inhale too deeply. Drake kept his silvering chin pressed to the ground and his dark eyes on Leo, forehead furrowed as if he were waiting for bad news.

“Not a big fan of

eau de

lake water?” Tom appeared to be addressing the cat.

Leo gave Tom the “foolish human” look, then turned back to Drake, crouching to sniff the dog’s lips.

“Wonder if he smells the blood,” I said through a mouth full of chicken.

“What blood?” Tom clearly was not as obsessed with the bloody bag

as I was. He watched the cat settle belly-down into the grass, tuck his paws under his chest, and wrap his tail along his left side with the white tip twitching next to his elbow. “Ever feel like he thinks people are too stupid to live?” Tom’s new to cats. In fact, he had told me a few weeks earlier that Leo’s the first cat he’s ever really gotten to know, and Tom had fallen hard for my little orange tabby.

“Nah.” I tossed a chicken thigh bone onto the paper towel I’d spread for refuse. “He just doesn’t suffer foolish questions easily.”

“Ah.”

“Speaking of questions, what do you really think about that bag?” As I spoke, Jay and Drake swivelled their heads and aimed their ears toward the yard next door. My neighbor Goldie had just stepped through her back door wearing a caftan that glowed neon lime under her yellow porch lights.

Tom followed my gaze and smiled. You have to smile when you see Goldie. Parts of her never left the sixties, when, true to Scott McKenzie’s song, she had gone to San Francisco, worn flowers in her hair, and changed her name from Rachel Golden to Sunshine Golden and, ultimately and legally, Golden Sunshine. She came back here a decade ago when her parents died within two weeks of each other, leaving her the house and a tidy pile of money. She had filled the yard with flowers and had been my friend through bad times and good.

Jay looked at me, back at Goldie, back at me, twitching to go but obeying my command to stay. I told him he was a good boy, and free from the “stay” command, and he raced for the fence, Drake right behind. Leo jumped out of the way, glared at the dogs, and shook a paw as if flinging away his disgust at their lack of manners. Feline dignity restored, he trotted after them. The commotion caught Goldie’s eye and she waved. That was our signal to join the gathering at the fence.

six

“She doesn’t look good,

does she?” I asked as I put the remains of the cole slaw in the fridge. I had been speculating on Goldie’s health all summer, to myself and to Tom. It was all I could do. I’d tried everything from conversational fishing to direct questions, and Goldie always insisted that I was being silly and then changed the subject.

Tom dropped the chicken bones into a garbage bag, pulled it from the trash can, spun it, tied the knot, and looked at me, the closed bag dangling from his hand and a weary look on his face. “She’s not well.”

“That’s what I think. She’s lost too much weight and her color is off.” I tossed Jay’s eyeless, one-eared squeaky bunny and a newish floppy-legged fleecy sheep into the living room to clear the kitchen of dogs and started a pot of tea. “I’ve asked and asked and she says she’s fine. Maybe she thinks she is fine. I just …”

A hand on my arm stopped me mid-wish and I turned. “No, Janet, I mean, she’s not well.” Tom’s brown eyes, usually so warm and open they make me hungry, had gone a little murky, and a sliver of fear pricked at my mind. “I ran into her at the co-op a few days ago.” He hoisted the bag in his hand and turned toward the back door. “Let me take this out. Then we’ll talk.”

I think my jaw dropped open, and I know my knees started to give. I sank into a chair at the table. The bunny and sheep appeared in my lap. The dogs watched me, mouths open in panting grins and eyes sparking with anticipation. I tossed the toys, but my heart wasn’t in it. Dogs know, they just know, and the next thing

I

knew I had a black chin on one thigh, a white paw on the other, and four worried eyes telling me that I was never alone. I ran a hand along each lovely skull, the black hair on Drake’s crisp and cool, the copper and silvery merle of Jay’s slippery as silk. I folded at the waist and laid my face between theirs and felt my eyes fill, not just for Goldie, whatever was wrong, but for all the sorrows that chip away at our souls.

Tom let the door bang shut, breaking the spell. The dogs ran to him and I mashed the heels of my hands into my eyes to make my tear ducts behave.

“Settle, guys.” Tom spoke softly and pointed toward a spot along the kitchen wall. In cooler weather I keep a big dog bed there, but in summer Jay prefers the cool vinyl, so the bed was stashed in the laundry room. The dogs looked at Tom and back at me, probably in hopes that I would countermand the directive. I shrugged at them and they went and lay down.

The kettle began to whistle, so I got up and grabbed it. I poured a bit of boiling water into my ancient bone china pot, swished it and dumped it, drizzled in some loose jasmine green tea, and filled the pot to steep. I focused on taking deep, cleansing breaths to calm myself, and teared up again as I realized that Goldie had taught me to do that.

Shake it off, MacPhail.

I set the pot and two mugs on the table, sat down, and braced myself. Tom was about to tell me whatever bad thing he had learned about Goldie when the doorbell rang.

seven

“Wowser!” I said. “Who

are

you, and what have you done with my friend Jo?”

The woman on my front porch wore a V-neck peach-colored silk blouse and a skirt three shades darker that draped softly around her slim form. Gold chandelier earrings sparkled beneath her wavy short brown hair, and a delicate gold chain hung just below the notch of her collar bones. Quite a contrast from her usual khaki chinos, white shirt, and navy blazer. “You have makeup on!”

I was used to seeing Jo Stevens in her tough-cop guise and was surprised to see her cheeks go a soft rose. “Oh, come on. I dress like a girl occasionally.”

“I’ll say!” Tom stood framed by the kitchen doorway, each hand in a dog’s collar. All three males had pretty much the same adoring look on their faces, although Tom’s tongue didn’t actually hang out. I realized with a start that my right hand was trying to fix my own messy hair, and I made it stop. Tom sent Drake and Jay to their spot in the corner, then bowed and gestured Jo into the kitchen, and I felt even frumpier as I watched her glide to a chair. But as she passed him, Tom turned and winked at me and bowed again. “Milady.” As I moved by him he pinched my butt, and I swatted at his hand with deep and unreasonable pleasure.

Jo declined my offer of tea. She asked Tom how his summer research in New Mexico went, then got down to business. “So what’s up?” The notebook and pen she usually stowed in her breast pocket emerged from a drawstring pouch lavishly embroidered and beaded in shades of sea and sky.

Tom excused himself to retrieve the canvas bag from his car while I gave my five-second rendition of Drake’s mysterious find and then asked, “Hot date?”

Jo grinned at me.

“Come on, girlfriend, give it up!” But Tom’s return put the kibosh on the juicy details. He handed Jo the plastic bag containing the canvas tote. She lifted it toward the ceiling light. “Huh.” The water pooled along the plastic seam still had the pink cast I had noticed at the lake. Definitely not a reflection of the setting sun.

Jo glanced at Tom, then looked at me. “So?”

“So, I think that’s blood on the bag, and there’s a torn bit of a hundred dollar bill inside. At least that’s what we think it is.”

Tom added, “And a feather.”

“Maybe a game bag?” She glanced at her watch. Not the big round face of the black-banded Fossil she usually wore, but a dainty little gold number that shared her wrist with a delicate gold bracelet. “I mean, if someone was out there hunting, they’d need a game bag to carry their victims home, right?”

Tom and I looked at each other. I hadn’t thought of that.

“That whole area is posted no hunting, so it’s unlikely,” said Tom. “And anyway, it was a long red feather, not from any local game birds I can think of.” He looked at the bag in Jo’s hands. “And that’s not a typical game bag.”

I smiled at him, encouraged that he finally seemed to be on my side, and added, “Besides, why would a blood-soaked bag with part of a hundred dollar bill in it be lying out on a little private island like that?”

Jay and Drake both lifted their heads and looked at me, attuned as always to shifting emotions in their human companions. For my part, I was attuned to Jo’s apparent lack of concern. Or maybe it was annoyance. She

was

off duty, after all.

Jo sighed. “You have a permanent marker handy?”

I produced one and she made some marks on the plastic bag.

“Okay, I’ll look into it. It is a little weird, but there’s no evidence of a crime.” She stood and smoothed her skirt. “Tell you what. One of you meet me there tomorrow and I’ll take a look at the island. Right now, I’m off duty. Gotta go.”

The dogs started to follow but Tom signaled them to lie down and stay, and they did. We walked Jo to the door and made arrangements for the next day, then watched her get into the passenger side of a nifty little sports car. Couldn’t tell you what kind, other than low and sleek and an indefinite color under the glow of the streetlight. I couldn’t see the driver, either.

“Hunh.” I didn’t exactly want to be Jo’s age again, but still, another sprig of loss grew in my heart.

Tom wrapped his hand around mine and gave it a little squeeze, making me wonder, not for the first time, which came first, the astute people-watching skills or the anthropological training.

“She looks great.” I was startled by the whiny little edge in my voice.

“She does,” he agreed, and the sprig in my heart morphed into a sequoia of jealousy that I knew was stupid, and yet, there it was, until he said, “Then again, a bit young and skinny. And there’s not nearly enough dog hair on her duds.” He pulled me back from the door, pushed it shut, wrapped his arms around me, and kissed me silly. When all rational thoughts were cleared from my head, he slid his cheek along mine and said, “Maybe we should make ourselves comfortable.”

“Mmmmm.” We turned away from the door and stepped over the dogs, who had crawled closer for a better view. Drake slapped his tail against the cool vinyl and Jay waved a lazy white paw our way, then they both sighed and went back to dozing. Tom draped his arm over my shoulder and steered us to the living room couch, where we were beginning to get serious when a knock on the back door launched the dogs off the floor and turned our heads toward the kitchen. The door swung open and a plate of cookies barged through, followed by Goldie, her long braids like liquid silver against the fuschia caftan and her smile like the sunshine for which she had named herself. A pang of guilt hit me for having let my hormones keep me from asking Tom what he knew about her health, and now that would have to wait again.

“You have to come eat these,” she called from the kitchen, seemingly oblivious to the passion play underway in the living room. “I don’t know why I baked so many. If I eat them all myself I’ll be a blimp.”

Tom pulled himself off me and then pulled me off the couch. We both refastened and tucked in clothing as we followed our noses to the kitchen. Jay and Drake were already standing by the counter, muzzles aimed toward the plate of cookies that Goldie was uncovering. They were having an olfactory orgy this evening.

“I just heard from my source at the county building. That preacher, that Regal Moneypincher …”

Tom choked on his cookie and I said, “Regis Moneypenny.”

“That’s the one. He’s buying up land all around Cedar Canyons Road and plans to put up some kind of commune or something.” Goldie used the back of her wrist to wipe a stray curl from her forehead. “Not my kind of commune, you know. We worked and shared and had barely a pot to, well, cook in. No sir, he’s planning some kind of walled, gated, gotta-have-a-lotta-money place.”

“Sounds like most of the new developments around here,” said Tom, grabbing another cookie. “These are great. What

are

they?”

“What do you mean, …” I began.

“Lavender and white chocolate.”

“… your ‘source’ at the county …,” I stopped as Goldie’s words sank in. “Lavender and white chocolate?” I reached for one. “Really?”

“He’s going to ruin that beautiful land up there.”

Tom nodded and said something like “Rmftt” through a mouthful of cookie.

“What kind of source, Goldie?”

“Secret.”

I flashed on an image of Goldie meeting a guy in a trench coat in the shadowy concrete parking canyon of the City-County Building. “Who?”

Goldie looked over the top of her glasses at me. “What kind of secret would it be if I told you who?”

“She could,” Tom said, elbowing me and winking at Goldie, “ but then she’d have to kill you.”

Goldie pulled a chair out from the table and sat down with a huge sigh. “It’s no laughing matter. Those little lakes and the fallow fields up there are on the migratory flyways for birds and butterflies both, and besides, how could anyone want to bulldoze and pave that lovely part of the county?”

“We were just out there,” said Tom. “Didn’t see any new development going in.”

“No, he’s just applied for the permits. My

secret

source,” she stressed the word and looked at me, “said there were all kinds of things on the building list. Not just houses. Weird things.”

“It is a spiritual center of some sort. Maybe they need another church?” I envisioned the palatial building they had now and thought it seemed doubtful, if obvious.

“Ladies,” Tom said, “I’m going to call it a night. I have to work on a paper in the morning, and Janet, you’re out early, too, right?” He pulled a plastic bag out of a box on the counter and shoved several cookies into it. “So I shall gallantly protect you from these calories, and ride off with my faithful dog.” He gave me a quick kiss, whispered “I think she’s here for a while,” and left.

I tried to listen closely to Goldie, but couldn’t keep my thoughts from wandering. If Moneypenny was planning to develop the area around his spiritual center, there would be more people than Goldie eager to stop him. Especially if he was planning to build “weird things,” whatever that meant.

“What do you mean by ‘weird things,’ Goldie?” I asked.

“An aviary, for one. Big one.”

That didn’t seem too weird to me, although I wasn’t sure how it fit into a Spiritual Renewal Center. If there was something odd about his proposed buildings, though, could there be a connection between his plans and the bloody bag Drake had found? I didn’t care what anyone said, I was sure the stain on the bag was blood, and the thought of what that might mean made my stomach turn. I set my half-eaten cookie on a napkin and put the kettle back on. I could tell that Tom was right, Goldie did seem to be good for at least another hour. Still, it wasn’t even ten. I realized that I was disappointed that Tom had left, and a little angry at both Tom and Goldie. What were they hiding from me? And what in the world was going on at Twisted Lake and Treasures on Earth? I was suddenly determined to find out, with or without their help.

eight

The next morning I

was out the door early despite the fog in my brain from lack of sleep. Goldie had stayed until nearly midnight. I tried several times to steer the conversation to her health, but she was on a roll about land-raping developers and crazy cult leaders, and she dismissed my concerns about her with a cheery, “Bah! I’m

fine

, Janet!” By the time she left and I’d showered, taken Jay out one last time, and locked up, it was nearly one a.m. Even then I tossed and turned for at least another hour, pondering the meaning of Drake’s bag and its contents, Goldie’s evasiveness, and the likelihood that I would oversleep.

I didn’t. I woke up about two minutes before my alarm was set to go off and dragged myself out of bed. A prominent women’s magazine had commissioned a photo essay on a day in the life of a woman veterinarian, and I was scheduled to spend every day that week traipsing around my vet’s clinic with my camera. It’s a two-vet office. Jay and Leo usually see Paul Douglas, but I would be shadowing his partner and, as it happens, his wife, Kerry Joiner. Dr. Kerry Joiner had officially linked

up with Dr. Paul Douglas, in business and in life, a couple of years ear

lier. I knew her mostly from dog-training classes and dog shows. She was perfect for the magazine article—five years out of Purdue vet school, petite and perky as the Pomeranian she owned, strong enough to hoist a hundred pounds of dog onto an exam table, and lots of fun to be around.

The clinic was in turmoil when I arrived. The lobby, at any rate. One of the two veterinary technicians had called the week before

from Key West and announced that she wasn’t coming back. The other

called in sick half an hour before I arrived, and the second receptionist wasn’t due until nine o’clock. Peg, the office manager, was scurrying between the clamor of Monday-morning phones and the chaos of Monday-morning clients. This particular Monday morning was deafening, and as I walked by the front desk I heard Peg mutter something about sedatives.

I spotted my across-the-street neighbors, Mr. Hostetler and Paco,

the Chihuahua, at the far end of the waiting room. Mr. Hostetler’s five-year-old grandson, Tyler, was leaning into his grandpa and gently stroking Paco. I waved as I asked Peg, “What can I do?”

Peg turned grateful eyes my way and slapped a file folder into my hand. “Any chance you could escort the Willards to exam room one?”

I had the oddest vision of rats, and realized the name made me think of that old movie about a kid named Willard who sicced his trained rodent on his enemies. Turned out in this case we were faced not with a rat but a brat. I missed out on having children, not by design, but I have learned a few things from my years as a dog and cat owner. One thing I know for sure is that young animals have to be trained. All kinds of young animals, including the human ones. Lacking direction, some young animals do everything in their power to discourage their mothers—and anyone else within earshot—from ever reproducing again. The Willard child was one of those.

The Willard puppy was named Hummer. Big name, whopping big puppy. His file showed that Hummer weighed sixteen pounds at his last visit, when he was seven weeks old. Now, a month later, he had more than doubled in weight and had a surplus of puppy energy. Not that I’d expect less of a Golden Retriever crossed with Something Really Big. The shape of his head made me suspect Newfoundland in his lineage, and I considered suggesting water dog training to channel his enthusiasm. Then I really looked at Mrs. Willard and decided that mud and wet dogs were probably not her thing.

When Hummer heard me call his name, he spun toward the sound and leaped at me, yanking Mrs. Willard out of her seat. If he’d had better traction on the vinyl floor, his owner might have found herself skidding face-first behind him. Luckily for her, the pup’s cartoon scramble over the slick surface gave her a chance to get her strappy Ferragamos under her, and she clattered toward me, her arm pulled taut along with the leash that was, apparently, purely decorative. The rest of the clients in the waiting room hugged their pets or pet carriers close.

“Hummer, stop that!” pleaded Mrs. Willard. Hummer planted his humongous feet against my waist and pasted a fist-sized glob of sticky drool to the smock I’d borrowed from the missing techs.

I was wondering how we might set up a photo of a slobbered-up vet for my photo essay when a high-pitched scalpel of a voice began to chant, “Hummer, stop that! Hummer, stop that! Hummer, stop that!” The owner of the voice jumped up and down on chubby

pink-clad legs a couple of times, then grabbed the leash halfway

between her mother and Hummer and pulled with all her four-year-old might.

Hummer spun away from me, circled the screeching kid, and wrapped his leash twice around her ribs before you could shout, “Down! Stay!”

“Tiffany dear, please be quiet.” Mrs. Willard was remarkably calm.

Tiffany dear was remarkably loud, and she raised the volume when Hummer gave her face a good slurp. “Aaaaaaa! Bad dog! Bad dog!”

Pandemonium broke out in the back room as a chorus of barking and howling mingled with Tiffany’s racket. A couple of dogs in the waiting room joined in. Paco started a staccato series of barks but was quickly stifled by Mr. Hostetler’s hand around his muzzle, a motion mirrored by Tyler, who had clapped his hand over his own mouth and widened his eyes. A dainty little Border Collie whined and strained against her leash, hot to organize the unruly mob. Hummer bounced up and down against the howling kid, woof-woofing and mouthing bits of clothing. Mrs. Willard reached for Hummer’s collar, then snatched her hand back with a gasp and looked at it.

“Did he bite you?” I asked. I didn’t think the big galoot would do it on purpose, but those needles they call baby teeth can cause some damage if you get in the way.

“I broke a nail! Awww, I just had them done!” She held her hand in front of her eyes, a pout wrinkling the otherwise perfect skin around her mouth. I never have any nails to break, so the apparent depth of the tragedy was lost on me.

I wanted to chime in with the screamers. Instead, I tossed the file folder onto the counter and said, “Let me help.” I got the back of Hummer’s collar in my left hand and put my right hand on Tiffany’s chubby little shoulder. “Quiet!” Child and dog both froze and stared at me. I unhooked the leash from Hummer’s collar and unwound it from Tiffany, then put it back on the dog. Tiffany burst into tears and resumed screaming, but at least the puppy was under a semblance of control. I told Mrs. Willard to bring the folder and follow me. As I led the unruly horde down the hall, applause broke out in the waiting room. My debut as a veterinary assistant was off to a rip-roaring start.

nine

As any experienced dog

breeder will tell you, not all females are endowed with a full set of mothering instincts. Judging by Tiffany dear’s too-well-fed form and too-expensive-for-kids couture, I could see that Mrs. Willard was at the head of the line marked “Instincts for Feeding and Clothing the Young.” Judging by Tiffany’s exquisite brattiness, I assumed that Mrs. Willard had skipped the line marked “Managing Unruly Offspring.” Perhaps she relied on other people to do it for her.

I have no burning desire to manage anyone’s children, but Tiffany dear forced my hand. She leaned one dimpled hand of her own on the seat of the bench in the exam room and swung one pink-stockinged foot back and forth, peering at me from the corner of her eye. Each forward swing of her leg brought the toe of her shoe a little closer to Hummer’s head. The puppy was lying down and panting happily, and I wanted him to stay that way until Dr. Joiner arrived. A shoe to the ear wouldn’t help.

“Careful you don’t kick your puppy.” I forced myself to smile.

Tiffany dear stuck her tongue out at me. Her mom giggled and squirmed in her seat. She reached out to stroke her daughter’s curly brown hair, but the kid dodged her hand, so Mrs. Willard scratched Hummer’s head instead. A glint below her throat caught my eye, and I looked at the pendant hanging from a delicate chain. It looked like a cross with half a heart hanging from one side, and although I thought I had seen something like it before, I couldn’t think where.

My attempts to remember were cut short when Tiffany pointed at me and whined, “I don’t like that.”

That?

I thought. But the kid went on, “It looks like Polly and I

hate

Polly.” She stuck her lower lip out so far I thought she might trip over it.

“Well, that one is green, dear,” said Mrs. Willard, “and Polly is blue, so it doesn’t really look like Polly, does it?”

“I hate Polly!” Tiffany’s voice escalated in pitch and volume with every word. “I hate all the birds!”

I turned to see what in the world they were talking about. On the wall behind me was a painting of a green parrot of some sort. I turned back to Tiffany, smiled at her, and said, “I think that’s a very pretty bird. Why don’t you like it?”

Without a word, Tiffany popped off the seat and danced a pirouette. As she turned toward the wall behind her, the poster of “Cats of the World” caught her eye. She scrambled onto the bench and ripped a ragged triangle from the bottom third of the poster.

Mrs. Willard turned her head toward her daughter, and said, “Tiffany dear, please don’t do that. Be good and we’ll stop for ice cream on the way home.”

Just what this kid needs

, I thought.

Calories and sugar to reinforce her bad behavior

.

Tiffany’s hand started to reach once more for the wounded poster, but Mrs. Willard didn’t move. I suppose she was in nail-preservation mode. With reflexes honed by years of handling unwilling and untrained animals, I took hold of the little dear just above her elbow and, with marvelous restraint, pulled her gently around and sat her down on the bench. “Please sit down, Tiffany.” I tried to keep the snarl out of my voice. “That bench is pretty slippery. You might fall off and hurt yourself.” She glared at me, glanced at her mother, and started to cry. The kid deserved an academy award. I kept the smile pasted to my face and left the room.

Dr. Joiner was squatting in front of a large cage watching a newborn tan-and-white Bulldog nestle against his mother’s warm belly. Agnes, the mama dog, didn’t seem to mind that her puppy’s should

er was firmly planted against her stitched-up incision. She had taken

to her new son immediately, not always the case with caesarian deliveries, and she looked immensely pleased with her offspring.

“Who or what was carrying on out there?”

“The Willard kid.”

Dr. Joiner stood, her face scrunching up with obvious dread. “Oh, no. Don’t tell me they’re here for me?” I nodded. She slumped against the door frame and whined, “Why can’t she see Paul instead?” She was still muttering as she stalked down the hall toward the room. I thought of retrieving my camera but decided to wait for more appealing subjects than the Willards for my photo shoot.

“They are really weird,” said Dr. Kerry.

“Who?”

“Willards.” She stopped, took my arm, and leaned in so I could hear her lowered voice. “Money out the yin yang, and apparently nothing to do with it except buy expensive stuff.” She released my arm. “Sorry. I shouldn’t be gossiping about clients.”

“Mum’s the word.”

“I love their pup. He’s such a

big

sweet galoot. She told me they paid $1,800 for him.”

“But he’s a mixed breed.”

“Right. But they were sold a bill of goods along with him. Golden by Newfie cross labeled ‘Goldenlander.’ Can you believe it? Even came with papers from some fly-by-night registry. No health clearances on the parents, of course.”

I understood her frustration, having spoken to many pet owners, and said, “People think if you cross different breeds you automatically get healthier dogs.”

Dr. Joiner shook her head and muttered, “So gullible.”

We rolled our eyes at one another and walked the last few yards to the exam room door.

Hummer had restarted his engine and was bouncing around as wildly as he could manage in the three feet between the bench and the examination table. Dr. Joiner bent to pet him and Mrs. Willard told him over and over again to sit. He didn’t mind any better than her kid, but he hadn’t destroyed anything. Everyone in the room focused on the puppy. Everyone except Tiffany. She was somewhere behind me, and I was just turning to see what the little dear was up to when the metallic protest of a drawer being yanked open filled the room.

“Tiffany dear, don’t do that.” True to form, her mother again made no move to restrain the child, and her voice was too tentative to have any effect. I thought back to my own mom, who in better days had brooked no nonsense from me or my brother, Bill, especially in public—clearly a different breed of mother from Mrs. Willard.

The oblivious child was on tippy toes, reaching a hand above her head and into the drawer. I half hoped she’d accidentally jab herself with a syringe full of anaesthetic, although the possibility was remote since I knew from my tour of the clinic that they don’t keep syringes or drugs in the exam rooms. So, for the second time in five minutes, I gripped Tiffany’s chunky arm and pulled her away from trouble. Or so I thought.

ten

Trouble seems to be

my new middle name. Not that I cause it. I just find it lately. I mean, how many photographers find blood-stained bags in idyllic settings or uncontrolled children in veterinary clinics? I was wondering whether I should switch my photographic specialty from living things to, oh, say, architecture when Dr. Joiner’s voice brought me back to the moment.

“Is it broken?”

Tiffany dear had yanked the drawer far enough out of its slot that it stuck when I tried to push it in. “I think just off track.” I released Tiffany’s arm and tried to give her the glare my mom used to use to scare the bejeepers out of me and Bill. Either I wasn’t as terrifying as Mom or Tiffany was gutsier than I was as a kid, because she glared right back at me. I was reluctant to turn my back on her—an instinct

that turned out to be sound—but someone had to, so I squatted to examine the bottom of the injured storage unit. I pushed up on the

handle and jiggled the drawer to the right, felt it fall back into the track, and tested it. “All better.”

Tiffany stood against the wall, kicking the new paint with her heel. The hostile glare had been replaced by a chilling gaze that bespoke more plotting than an Agatha Christie collection. I thought the leash should be on Tiffany rather than Hummer, but knew that it would be every inch as ineffectual as it was with the pup as long as Mrs. Willard held its other end. In any case, the child’s mother hadn’t said a word as her daughter terrorized the exam room, and in the aftermath she looked calm as a sleeping dog. I wanted some of whatever she was taking.

“Well, then, let’s have a look at this puppy.” Dr. Joiner talked a little too fast and smiled a little too cheerfully.

I unsnapped Hummer’s leash and handed it to his owner. As I hoisted

him onto the exam table, I checked the whereabouts of the demon child. She was still busy planting black scuff marks on the wall to my left.

Dr. Joiner pronounced Hummer’s heart and lungs healthy, gave him his shots, and began to trim his nails. He wriggled and squirmed

, alternating between licking Dr. Joiner’s face and trying to eat the clippers, so I encircled him with my arms to immobilize him, or at least slow him down. Unfortunately, holding him still made me a sitting duck.

Come to think of it, I wish I had been sitting. As it happened, I was on my feet and leaning forward against the table to hold the puppy for his pedicure. Mrs. Willard sat on the bench, still filing her own broken nail and smiling like the Mona Lisa. And for a brief instant I had no idea where Tiffany dear had gotten to. Then, in the time it took to clip one puppy nail, little hands shot up under my smock, latched onto the top of my easy-waist pants—both pairs—and slid them down to my ankles.

“Owww!” A sharp pain shot from my butt to my brain. I didn’t immediately recognize the sensation, but quickly realized it was caused by enamel penetrating flesh.

“Wha …?” Dr. Joiner stepped back from the table, startled.

“She bit me!”

The vet glanced at Hummer’s distinctly male abdomen and looked

confused. I pushed the puppy toward her, determined to free my hands so I could swat my assailant.

Mrs. Willard stood at the end of the table, nail file in hand, staring at Hummer. “He bit you?” She turned enormous contact-turquoise eyes on me.

“Not your dog!” I growled, craning my neck over my shoulder and running a hand over my complaining behind. “Your kid!”

Tiffany dear was backed up to the wall again, grinning at me. For an instant, I could have sworn I saw long fangs dripping gore. I looked at my hand and showed the smear of red across my palm to Dr. Joiner. She scooped the bewildered looking Hummer into one arm and opened the door to the back room with the other. “We need some help here. Now!”

I realized with horror that the only one who could be in the back room was Dr. Douglas. And before I could react to the thought, there he was.

Dr. Joiner shoved Hummer into her husband’s arms and pushed the two of them toward the door to the waiting room. “Janet’s been bitten.” She grabbed Tiffany’s hand and hauled her away from the wall and toward her mother. “Paul, please keep the Willards out front for a few minutes.” To Vampira’s mother she said, “Make your daughter sit down and stay put.”

Mrs. Willard gaped at the blood on my hand and, for the first time, came to life. “Oh my God!” She pulled her daughter to her. “She could get sick!” At first I thought she was concerned for me. Bites of any kind are dangerous, and a friend who runs a preschool had once told me that human bites that break the skin often result in horrifying infections.

“I think I’m o …,” I started to say, but Mrs. Willard cut me off.

“Have you been tested?” It was becoming clear that Tiffany got her weapons-grade screech from her mother. “Oh my God, Tiffany!”

“Tested?” I asked.

Dr. Joiner put a hand on Mrs. Willard’s shoulder and aimed her toward the door. “Your daughter just bit this woman and injured her. You could show a little concern for Janet.”

Dr. Douglas seemed to be trying to catch up on the situation. “You got bitten?” He looked doubtfully at the puppy slurping happily at his chin. As he walked past the examining table, I bent over to pull my pants up under my almost-long-enough smock, confusing him even more.

“The dog didn’t bite her,” said Dr. Joiner, “but watch out for the kid.” She gave her now-grinning partner a final nudge and pulled the door shut.

“Okay, let me see.”

“It’s fine.”

“It’s not fine. She broke the skin. Let me see.”

“No, rea …”

She crossed her arms, cocked a hip, and waited, her green eyes daring me to object again. With a sigh, I pulled my pants back down to my knees and leaned forward against the steel tabletop.

“Wow. That’s bigger than I expected.”

“Hey!”

“The bite. It needs a stitch or two, and antibiotics.”

“Can’t you just clean it and stick a bandage on it?”

She stood up and reached for some Betadine and a cotton pad. “I’ll clean it and tape a pad to it, and then you’re going to the ER.”

“No!”

“Don’t argue, Janet. I can’t treat you, and you know as well as I do that you don’t screw around with bites.” The muscles around my eyes and in my fanny flinched as Dr. Joiner dabbed at the wound. She taped a gauze pad bigger than some bikinis to me and signaled me to pull my pants up. “I should fire you, you know.”

“Oh yeah?”

“Yeah. How dare you flash my husband?”

“Well, if you remember, I was shanghaied for this duty. You can’t fire a slave.”

“Listen, we’ll pay for everything. Get HIV and hepatitis tests while you’re there. Wouldn’t be surprised if the Willards raise a fuss.”

“But

she

bit

me!”

“Just trying to be proactive.”

“Wow,” I said, looking at my blood-stained hand. “Just wow.”

“I know.” She sighed. “I’ll have Peg drive you. Nancy will be in soon and she can get the phone.”

“But …”

Dr. Joiner signaled “stop” with her hand. “The only butt I’m interested in at the moment is yours. Get it taken care of.”

eleven

Peg laughed all the

way to Parkview Hospital. Or most of the way. She paused for a moment of outrage when I told her how Tiffany dear had ripped the poster and jammed the drawer, but my painful humiliation at the hands and jaws of Mrs. Willard’s demon spawn sent her into whoops of laughter.

“I’m not laughing

at

you, you know,” she gasped between giggling sprees. “But you have to admit it’s pretty funny. Not that a kid who bites is funny, but …”

I gave her a dirty look but she was watching the road and missed it, so I complained out loud. “It hurts like hell. That kid is headed for big trouble if you ask me.” My body listed toward the passenger window to spare my damaged cheek.

“Yeah, they better wash her mouth out with soap so she doesn’t get sick.” She wiped at her eye.

“Yuk yuk.” I thought about Dr. Joiner’s instructions. “Did Kerry tell you I need HIV and hepatitis tests?”

Peg nodded, then grinned. “No wonder Dr. Douglas had that funny grin on his face when he came out!”

“Great. I suppose this will be the topic of many a tasteless comment every time I come in for the next few months.”

“Oh, more like years. You’ll be …” The rest of the sentence disappeared in an incoherent squeal that turned into more giggles. Peg finally got a grip and repeated in a voice two octaves too high, “You’re gonna be the butt of a lot of jokes.”

I scowled out the window.

Peg recovered some control and, aside from her periodic giggle, we rode in silence until I said, more or less to myself, “Treasures on Earth.”

“Huh?”

“Treasures on Earth Spiritual Renewal Center. Mrs. Willard’s pendant. It’s their logo.”

“Never heard of it. But I think Mrs. Willard’s husband is a minister of some sort.” She seemed to be pondering something. “Wonder how a minister’s wife affords those clothes.”

Mrs. Willard didn’t strike me as a seeker after spiritual enlightenment, but her duds certainly fit with the cars I had seen in the parking lot at the Center. I started to ask Peg what else she knew about the Willards, but the throbbing in my backside distracted me. “Why do these things always happen when my doctor’s office is closed?”

“Same reason these things always happen to people’s pets when we’re closed.”

Same reason we find suspicious items in the middle of nowhere during dog training sessions,

I thought.

Peg braked in front of the ER entrance.

I winced as I straightened out of the car. A security guard young enough to have a scattering of pimples across his cheeks hustled up to the car. “Do you need a wheelchair, ma’am?”

I wanted to slap him. When did I become a ma’am? “Thanks, but definitely not.” The last thing I wanted to do was sit down again, which of course is what the clerk told me to do while I gave her my information. Peg hustled in from parking the car and explained that she would be paying on behalf of the clinic.

“What species of animal bit you?” The clerk’s hands hovered over her keyboard. Her short green nails matched the beads at the ends of hundreds of tiny braids hanging from neat cornrows, and her name tag dubbed her LaFawn.

“

Homo sapiens.”

She started to type, apparently on autopilot, and then stared at me as the information sank in.

“A person bit you?”

“Yes.”

She gaped at me. “Why?”

“Because I’m so sweet?” I shrugged, and sighed. “Because she’s a little brat.”

LaFawn snorted and her beads clacked as she shook her head in disgust. “What did her mama do?”

“Not much. She was injured earlier.” LaFawn’s eyebrows rose. “Broke a nail.”

Another snort, then back to work. “Where were you bitten?”

“All Paws Veterinary Clinic.”

She looked at me as if I had a brain injury. “Where on your body?”

“Oh.” My hand went involuntarily to my left buttock. “My butt.” I could tell she was trying hard to suppress the grin that played along the edges of her glossy red lips. “Go ahead and laugh at me. Everyone else has.”

LaFawn leaned across her desk, a conspiratorial smile lighting her face. “I got bit in the butt once.” Pregnant pause. “By a skeeter.” LaFawn and Peg cracked up. I gave the clerk my best dirty look and she adjusted herself in her chair, cleared her throat, and wriggled her fingers in preparation. “Okay then! Are you taking any medications?” And so on.

LaFawn directed us to follow the blue line down the hall and

around the corner to where we would find a waiting area. She tried to insist that I occupy a wheelchair for the journey, but I was more insistent that I wasn’t interested in sitting down just yet, and off we went, one of us limping and the other still grinning her face off. A whirl of color flew into my peripheral vision as we passed another long corridor labeled Nuclear Medicine, and I turned to see a figure in white slacks and a loose-fitting tunic striped lemon, lime, and strawberry. What stopped me mid-stride was a vision of silver braids looped over the woman’s crown, but the vision disappeared through a doorway before I could call her name.

Goldie.

My feet seemed to take root as I stood at the intersection of the hallways. A series of images slid through my mind and suddenly took on a meaning I had pushed away for months, although I had suspected that something was off. I flashed on Goldie buying mountains of vitamins and herbals at the co-op last spring. Saw palmetto. Green tea. Cat’s claw. Goldie looking thin and pale. Tired, though she tried to hide it. What was it Tom wanted to tell me? He had left shortly after Goldie arrived the night before, saying he’d stop by late this afternoon after he showed Detective Jo where we’d found the bag at Heron Acres.

“Janet?” Peg had stopped and turned toward me, and all the jokes had abandoned her. “What’s wrong? Are you faint?”

The warmth of her hands on my arms unfroze my feet, and I let her steer me into the waiting room, but I still refused to sit. I fished my cell phone out of my purse, but the battery was dead. “Give me your cell.” She handed it over and I tried Tom’s office, cell, and home numbers, and left “call me’s” with Peg’s number on all three. I figured I would update the message as soon as I was near a working phone of my own.

The image of Goldie walking into that room wouldn’t get out of my head, and within minutes I had assured myself that nothing was wrong. She was probably there for a mammogram. She was fanatical about getting them, on time, once a year. And since spring she’d been slathering on high-test sun screen whenever she was out, so no wonder she looked pale compared to past summers. As for the supplements, she’d been into herbal therapies for forty years. I told myself she’d just been stocking up.

Peg leafed through every year-old magazine in the waiting room and gently relieved one of a recipe. I paced the floor and had put in several miles by the time someone could see me eighty minutes later. The nurse got me into a gown and situated face down on the exam table. I thought I’d be relieved to get the ordeal over with, but when the doctor walked into the room and I heard his name, I wished I had simply treated my injury with copious amounts of alcohol, taken internally.

twelve

“You know how sometimes

something you once wanted finally shows up at the worst possible moment?” I was sprawled on my stomach, a position I seemed to be assuming a lot lately. At least I was on my own bed and fully clothed this time. I was nose to nose with Jay, holding the phone with one hand and popping chocolate chips into my mouth with the other. In deference to my current weight-loss attempt I had stripped my cupboards of junk food, but twenty minutes of scrounging had turned up half a bag of these little darlings.

Goldie was still ranting about “some people’s children” and I wasn’t sure she’d heard me, but I plowed on.

“So there I was, in one of those stylish hospital gowns, belly down on an exam table with goose bumps all over my bare behind ’cause it was freezing in there, and in walks the doctor.”

“I bet it wasn’t a woman, huh?”

“Oh no.”

“Probably not a kindly old fart either, huh?”

“In your dreams.”

“Greek god?”

“Close.”

“So, tell me.”

“Neil Young.”

“The singer?”

“High school heartthrob.”

“Ohmygod! Neil the Hunk?” I had mentioned my girlhood lust for Neil to Goldie before. “He’s a doctor?” She squealed the last two words.

“That, or he just plays one in the emergency room.”

Goldie seemed to have caught Peg’s laughing disease, so I fiddled with Jay’s ear until the hooting on the other end of the line subsided.

“So, Goldie, what were you doing at Parkview?”

Silence.

“Goldie?”

“Oh, sorry, I’m making tea, trying to reach the oolong at the back of the cupboard.”

Uh huh.

“So, Parkview?”

“Just some routine blood work. Annual physical, all that jazz.”

Something was very wrong here, and although the frightened mortal part of me didn’t want to know what it was, the friend part of me did. “Goldie …”

She cut me off. “So tell me more. You’ve wanted Neil Young’s paws on your bare tush since you were sixteen. What an opportunity!”

“Goldie …” I thought of pressing for more information. Then I decided maybe the phone wasn’t the best medium for such a conversation and shifted back to my own story for the moment. “I haven’t exactly been holding a torch for him all these years.”

Jay inched forward, pointing his twitching nose toward the diminishing pile of chocolate chips and flicking his gaze back and forth between them and me.

“You can’t have chocolate.” I snarfed the last few chips to save him from possible poisoning. Theobromine, a chemical found in chocolate, is toxic for dogs. It’s the one reason I might hesitate to become fully canine, given the chance.

“Why can’t I have chocolate?” Goldie sounded confused.

“Talking to Jay.”

“So then what happened? Neil the Hunk is hunkered over your butt. Did he kiss it and make it better?”

“He put in a couple of stitches, gave me a prescription for two weeks worth of horse-size antibiotics, and went on to normal emergencies.”

“That’s all? No old home week?”

“He didn’t know who I was.”

“Sure he did.”

“He was polite, professional, and showed no hint of recognition.”

“How do you know? You were face down.”

“Funny.”

“Okay, brass tacks. Did you see whether he was wearing a ring?”

“Nope.”

“Well, there you go. You should have made your move.”

“No, I mean I didn’t notice. I didn’t have a very good view of his hands.” My brain zoomed in on an image of Tom’s smiling face and a wave of guilt sloshed over me.

As if she had read my mind, Goldie said, “I don’t think you should tell Dr. Tom about Dr. Neil.”

Despite my own twinges of conscience, Goldie’s comment hit me wrong. I mean, I like the guy a lot, but neither of us had made any firm commitment. “I’m not married to Tom.” Goldie let that go, although I knew her well enough to think I’d be hearing more on the subject later.

“So you were naked with Neil the Hunk and you didn’t do anything about it?”

“I wasn’t naked. I was draped. All that showed was the bite.”

“Bite, butt, close enough.”

“You try feeling sexy with a numbed fanny and a hospital gown.”

“That is a real bite in the ass,” and I thought

I’m never going to hear the last of this

. Goldie’s voice brightened as she thought of something else. “You have to go back to get the stitches out, right?”

“In your dreams. If I had to, I’d get Kerry, you know, Dr. Joiner, to do it, or just die with them in place. But they’re the dissolving kind.”

I didn’t tell Goldie, but I was relieved that Neil hadn’t recognized me. Despite the years, hearing his voice had made me yearn for something long gone, something we share only with those who knew us as children. And I had to admit that, from the little I could see when I snuck a backward glance, Neil wore the intervening years well. The body that had once been all elbows and Adam’s apple had matured well, and a glance over my shoulder had shown me that he still had those famous bedroom eyes, although they now suggested silk sheets and champagne rather than a quick fumble on a vinyl backseat. He struck me as the kind of guy who might prefer to unwrap a package of his own choosing rather than have one served up fanny first.

And that image, naturally, led my canine-oriented mind to an image of Mark Soudoff’s Miniature Schnauzer Heidi flinging her tail in Jay’s face at obedience practice last week. She wasn’t in heat. In fact, she’s spayed. But that never stops her flirting, and Jay flirts back, although he was “tutored” long ago. Of course, if he gets too fresh, Heidi offers to pin his ears to his nubby little tail. At the moment, Jay was gazing at the empty chocolate chip bag as a promising substitute for sex. He cocked his head, still flicking his gaze from me to the bag and back.

Goldie asked, “What?”

“Oh, just wondering if Neil likes dogs.” I winced as I forgot myself and rolled into a sitting position. Jay raised his head and listened for a moment, then leaped off the bed and raced out of the bedroom.

“Well, there’s a big black dog getting out of a car in your driveway, and he’s with a fella who does for sure like dogs. Looks like he comes bearing dinner. Again.”

I wasn’t sure if the flipflop in my chest was guilt or anticipation, but realized with a flush that I was glad the big black dog was here with his man, and not just because I wanted to hear about Tom’s trip to the lake with Detective Jo Stevens. I said goodbye to Goldie, rolled off the bed, and limped to the front door.

thirteen

As you might expect,

I often do have my camera handy when I need it, but not this time. Drake stood on the front porch with my evening paper in his mouth, tail waving and eyes gleaming. Tom stood beside him balancing a container of salad on a pizza box, eyes gleaming, my mail in his mouth.

“Are you two related?” I asked, taking the slightly damp paper goods from them and ushering them toward the kitchen. I limped along behind and tossed the mail and paper onto the pile that had sprouted on the table. “Let’s eat outside.”

Tom was already elbowing the back door open and sending the dogs out. He winked at me and asked, “Buy you a beer?”

“By all means.” He paused in the open door while I grabbed two Killians and a bottle of low-fat ranch from the refrigerator, then tucked the salad dressing between my arm and my ribs to fish a couple of forks and knives from the dishwasher. Good thing I’d run it last night.

Note to self: pay more attention to the house.

I glanced at the empty napkin holder on the table and ripped a length of paper towels off the roll beside the sink.

This is getting to be a habit,

I thought as I nodded at Tom to lead the way.