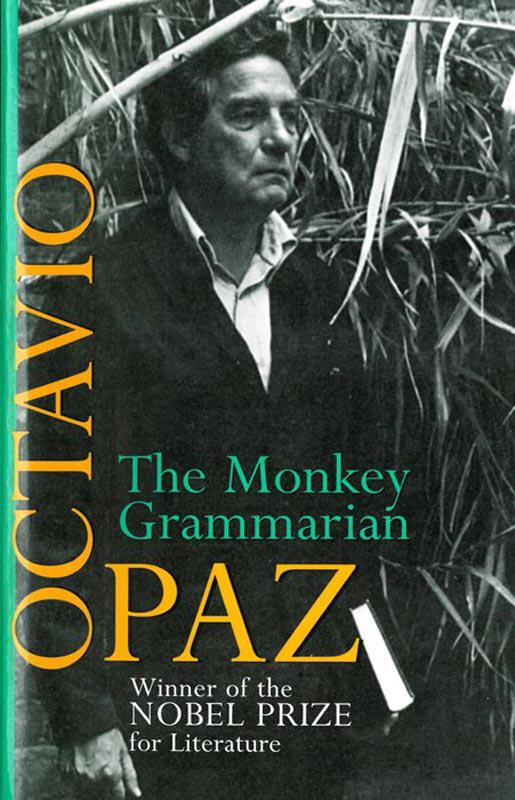

The Monkey Grammarian

| The Monkey Grammarian | |

| Octavio Paz | |

| Skyhorse Publishing Inc. (1990) | |

| Tags: | Essays, Literary Collections |

Hanumān, the red-faced monkey chief and ninth grammarian of Hindu mythology, is the protagonist of this dazzling narrative--a mind-journey to the temple city of Galta in India and the occasion for Octavio Paz, the celebrated Mexican poet and essayist, to explore the origin of language, the nature of naming and knowing, time and reality, and fixity and decay.

*

Selected Review

:

The very concept of grammar - a system in which language can be fixed, structured and therefore transformed - is one of the great achievements of Indian culture. In the past 50 years philosophers and linguists have devoted enormous intellectual energies to the investigation of how the concept was developed among the thinkers of ancient India, for whom the idea became a central problem in their philosophical tradition. Was language, our faculty for naming objects, given by God or did man invent it, either on his own or with powers borrowed from the divine realm? Through a species of time-space journey akin to Hanuman's, Octavio Paz explores this dilemma: ''What is language made of,'' he asks, ''and most important of all, is it already made, or is it something that is perpetually in the making?'' (

New York Times

)

*

About the Author:

Octavio Paz

(1914-1998) was born in Mexico City. He wrote many volumes of poetry, as well as a prolific body of remarkable works of nonfiction on subjects as varied as poetics, literary and art criticism, politics, culture, and Mexican history. He was awarded the Jerusalem Prize in 1977, the Cervantes Prize in 1981, and the Neustadt Prize in 1982. He received the German Peace Prize for his political work, and finally, the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1990.

About the Translator:

Helen Lane

was the preeminent translator of French, Spanish, Portuguese, and Italian fiction. Among the long list of authors she translated are Augusto Roa Bastos, Jorge Amado, Luisa Valenzuela, Mario Vargas Llosa, Marguerite Duras, Nélinda Piñon, and Curzio Malaparte.

TITLES BY OCTAVIO PAZ AVAILABLE FROM

ARCADE PUBLISHINGAlternating Current

Conjunctions and Disjunctions

Marcel Duchamp: Appearance Stripped Bare

The Monkey Grammarian

On Poets and Others

Copyright © 1974, 2011 by Editorial Seix Barrai, S.A.

English-language translation copyright © 1981, 2011 by Seaver Books

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Arcade Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or

[email protected]

.

Arcade Publishing® is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.®, a Delaware corporation.

Originally published in Spain in Editorial Seix Barral, S.A., under the title

El Mono Gramático

Visit our website at

www.arcadepub.com

.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-61145-481-9

HANUM N, HANUMAT, HANÜMAT. A celebrated monkey chief. He was able to fly and is a conspicuous figure in the

N, HANUMAT, HANÜMAT. A celebrated monkey chief. He was able to fly and is a conspicuous figure in the

R m

m yana

yana

, … Hanum n leaped from India to Ceylon in one bound; tore up trees, carried away the Himalayas, seized the clouds and performed many other wonderful exploits…. Among his other accomplishments, Hanum

n leaped from India to Ceylon in one bound; tore up trees, carried away the Himalayas, seized the clouds and performed many other wonderful exploits…. Among his other accomplishments, Hanum n was a grammarian; and the

n was a grammarian; and the

R m

m yana

yana

says: “The chief of monkeys is perfect; no one equals him in the sastras, in learning, and in ascertaining the sense of the scriptures (or in moving at will). It is well known that Hanum n was the ninth author of grammar.”

n was the ninth author of grammar.”

John Dowson, M. R. A. S.,

A Classical Dictionary of Hindu Mythology

TO MARIE JOSÉ

The best thing to do will be to choose the path to Galta, traverse it again (invent it as I traverse it), and without realizing it, almost imperceptibly, go to the end-without being concerned about what “going to the end” means or what I meant when I wrote that phrase. At the very beginning of the journey, already far off the main highway, as I walked along the path that leads to Galta, past the little grove of banyan trees and the pools of foul stagnant water, through the Gateway fallen into ruins and into the main courtyard bordered by dilapidated houses, I also had no idea where I was going, and was not concerned about it. I wasn’t asking myself questions: I was walking, merely walking, with no fixed itinerary in mind. I was simply setting forth to meet … what? I didn’t know at the time, and I still don’t know. Perhaps that is why I wrote “going to the end”: in order to find out, in order to discover what there is after the end. A verbal trap; after the end there is nothing, since if there were something, the end would not be the end. Nonetheless, we are always setting forth to meet…, even though we know that there is nothing, or no one, awaiting us. We go along, without a fixed itinerary, yet at the same time with an end (what end?) in mind, and with the aim of reaching the end. A search for the end, a dread of the end: the obverse and the reverse of the same act. Without this end that constantly eludes us we would not journey forth, nor would there be any paths. But the end is the refutation and the condemnation of the path: at the end the path dissolves, the meeting fades away to nothingness. And the end—it too fades away to nothingness.

The best thing to do will be to choose the path to Galta, traverse it again (invent it as I traverse it), and without realizing it, almost imperceptibly, go to the end-without being concerned about what “going to the end” means or what I meant when I wrote that phrase. At the very beginning of the journey, already far off the main highway, as I walked along the path that leads to Galta, past the little grove of banyan trees and the pools of foul stagnant water, through the Gateway fallen into ruins and into the main courtyard bordered by dilapidated houses, I also had no idea where I was going, and was not concerned about it. I wasn’t asking myself questions: I was walking, merely walking, with no fixed itinerary in mind. I was simply setting forth to meet … what? I didn’t know at the time, and I still don’t know. Perhaps that is why I wrote “going to the end”: in order to find out, in order to discover what there is after the end. A verbal trap; after the end there is nothing, since if there were something, the end would not be the end. Nonetheless, we are always setting forth to meet…, even though we know that there is nothing, or no one, awaiting us. We go along, without a fixed itinerary, yet at the same time with an end (what end?) in mind, and with the aim of reaching the end. A search for the end, a dread of the end: the obverse and the reverse of the same act. Without this end that constantly eludes us we would not journey forth, nor would there be any paths. But the end is the refutation and the condemnation of the path: at the end the path dissolves, the meeting fades away to nothingness. And the end—it too fades away to nothingness.