The Nature of Ice (11 page)

âWe won't see ele seals hauled out near the station until after the sea ice breaks out. Want to check'em out?'

âAbsolutely,' she says, collecting her camera. âI have a little-known fact for you,' she announces as they walk towards their bikes. She looks childlike, eager to share.

âHit me with it.'

âDid you know that just one half of an elephant seal tongue is enough to feed eighteen men?'

He smiles at this unexpected gem. âWho told you that tale?' The moment he utters the words they sound like a challenge. His lack of social grace is confirmed by a flash of her eyes.

âMy husband,' she says quietly, the bubble surrounding them burst. âDouglas Mawson's men shot an elephant seal at Commonwealth Bay, according to the journals Marcus is reading.'

Shyness returns to thread him in a knot. âYour husband got the raw part of the deal.'

She stacks her camera case and tripod on the bike rack. âHow's that, Chad?'

âYou're down here having all the fun while he's stuck at home reading about the place.'

He sees her bristle. âMarcus isn't

stuck at home

. It's what he chooses to do. And this,' she ties down her bag with a mangled knot, âis what I do for a living. It might seem like nothing much, but it's what I've spent years training for, in the same way you have with your trade.'

Chad registers her distress as she squeezes the bike helmet over her head. âI wasn't sayingâ'

âOnward!' She points at the island in the distance, snapping her visor closed and roaring away in a clatter of gears.

WALLOW, FREYA DECIDES, IS A fitting word for a gathering of malodorous elephant seals. Amid a squeeze of girths and press of bellies, these gargantuan blubber bags literally wallow in a mire of urine and foul-smelling sludge. One stretches the end of its flipper like a hand and nimbly pares off casts of its russet-coloured skin. The surrounding rocks are littered with sun-leathered, freeze-dried sheaths. Another elephant seal gapes a colossal pink mouth in a yawn, its jowls wobbling as it sneezes a voluminous spray of mucus in Freya's direction. That chore squared away, it slumps its bulk across a neighbouring back and returns to sonorous sleep. The wallow resounds with a cacophony of belches and farts. A bull's outrageously oversized snout acts as a foghorn, reverberating off the cliffs. Is it a

come

hither

, Freya wonders, to the new arrival they watched slop across the ice?

Freya skirts the perimeter of the wallow, springing across rocks and over spongy hillocks of dried, compacted sludge, surely representing decades of faecal waste. She takes a shortcut to where Chad sits watching, stopping herself short from jumping onto an apparent boulder that suddenly rises and blinks at her with soft brown eyes. The seal snorts, its quivering nostrils spluttering strings of snot across her boots. Quickly she retreats, noting the seal's jowls are scarred with a crosshatching of wounds.

Chad defends their graceless ways. âEles are highly social. During the summer moult they'll use one another as rubbing boards. The urea in the urine soothes their itchy skin.'

Two bulls rise up to full height and chest-butt in a rippling of blubber. They growl as they biff one another, the larger pressing the smaller backward with each thrust. The big bull, sporting a mountainous proboscis, buries its canines into the flesh of the other, wrestling the smaller challenger and dragging it from side to side like a dog tearing at a bone. The smaller bull soon retreats.

âBeachmaster versus wannabe,' Chad says. âNot ready to surrender his fiefdom this season.'

AT ZOLATOV ISLAND, THEIR FINAL destination for the afternoon, a pair of skuas settle on a nearby rock, as bold as you please, sizing up Freya and Chad as they share sandwiches and thermos tea. The birds, feathers ruffling in the wind, appear perfectly at ease in human company. This pair seems less interested in the contents of a packed lunch than in observing two strangers. Freya wonders who is entertaining whom.

âThey're not as feisty as people make out.' She takes her camera from her pack and composes the bird's face full-frame in her viewfinder. âI think they're regal and proud.'

âThey're sharp-looking birds.' Chad nods. âSmart as a whip.'

The skuas shift their focus towards the glacier in the distance, tilting their heads at the deep rumbles and explosions that issue from the ice. By the time Freya looks up at the frozen precipice, the ice has calved; all she catches is a billow of spray rising from the base where the ice has plunged into the water, the swell washing against the white cliff before the ocean subsides.

She turns to Chad. âMarcusâmy husband. I asked him. He didn't want to come.'

âFair enough,' he says. âIt's not to everybody's liking. How about you? Why Antarctica?'

She thinks for a while. âI guess it began when my father took me to see the

Fram

, Roald Amundsen's Antarctic ship, before we came out to Australia. I would have been only seven, but it made a huge impression on me. And then I saw Frank Hurley's photos. That was it. Hook, line and sinker. I had to find a way to come here for myself.'

âSo, here we are.'

âHere we are.'

What if Marcus had decided to come? How would he have coped? Or she, if he were here with her? He'd balk at the menial chores, socialising with the throng of people at the station; even today, out here, he'd quickly tire of the place. Marcus avoids social gatherings, even the monthly market days Freya loves. It's not that her husband isn't giving. When they're home alone, he smothers her with affection. When it's just the two of them he can be funny and playful. And quick; ask any of his students. Marcus can outsmart any mystery novel you hand him; he will, during Freya's favourite movies, spot gaps in plot and slips in continuity that are simply beyond her scope. But here? Forced to converse with people, some of whom he might otherwise scorn? She thinks of the times she had invited people to their home: it wasn't worth the angst, her husband visibly bored and drawing on his wit to belittle her before her friends. One excruciating evening he selectively derided their guestsâpeople from the magazine she worked for. The sting in his barbs. Furtive glances of disbelief.

Focus on the good things

, Mama says. And isn't every marriage a contract of concessions? She had freely given Marcus her pledge before they married,

no children

, never imagining the difference a decade would make. Perhaps she has Sophie to thank for changing her outlook: the unexpected joy in watching her niece grow from a tiny girl to a teenager, the flood of warmth she feels in being part of Sophie's life, entrusted with her secrets, in loving and being loved in return.

I'm forty-seven years old

, Marcus had silenced her.

I don't

intend slaving for the next twenty-some years to support an

iGeneration brat.

Marcus, she reminds herself, makes up for it in other ways. He dedicates hours to this project, encourages her career, not once has he objected to her wanderings. The man Freya married is rock-solid, never has he left one of his student's despairing, or made them wonder, should they give it all away? Of course she returns. She owes it to him, to them both, to bring home the perfect picture.

THE BEST OF THE DAY has gone, a freshening wind and the sky thick with cloud. Freya zips up her Ventile jacket past her neck warmer, grateful for the extra layers she has brought along to shield out the chill. As they pick their way over rocks towards the bikes, the lunchtime skuas swoop into view and circle above. They hover, perfectly balanced, their wings daubed with flashes of white.

âFarewell, skuas,' Freya calls. The birds shriek. âWhat's wrong with them?'

âWe must be near their nest.' Chad looks around. âWatch where you step.'

Freya is jolted by a sudden knock to the back of her skull. The force of the blow pushes her against the rocks. She wonders, momentarily, if she's been stoned. She rubs her wounded head and sees her fingers smeared with blood. A skua spirals above.

She scrambles up off the rocks and tries to make a run for it but the birds dive at her from opposite directions. Chad manoeuvres to the left to avoid them. The skuas shriek fearsomely, swooping again and again, a pair of maniacal demons in perfect formation. Freya cowers back against the rocks and drops to her knees. âWhy do they keep coming for me?' she cries.

She sees him stifle a smirk. âI guess they like you the best.' If she were not so terrified she would very much like to thump him.

âWalk in this direction.' He beckons. âHold your tripod above your head. They'll aim for the tallest part of you. Don't be scared.'

Freya edges towards him but can't help cowering each time she senses a movement. The sharp beak comes straight at her again and she hears herself whimper. The clawed feet drop like the landing gear of a stealth bomber. She ducks and runs after Chad, wielding her tripod like a white flag. The titanium legs jar in her grip with each new strike.

âThere's the nest down there.' Chad points to a scrape of gravel, indistinguishable from the surrounding rock except for the two large speckled eggs resting there. One of the adult skuas lands at the nest and paces, clucking its distress.

âA month away from hatching,' he says. âYou wait till you see the chicks. Little grey fluff balls.'

She takes up position behind Chad, thankful for a substantial shield, suddenly seized with the urge to laugh at how she must have looked. She is pulled up short by the sight of a penguin flipper and loops of fresh entrails that lie strewn around the nest.

âThe adélie would have been injured.' Chad senses her disgust. âThey wouldn't take on an adult otherwise.'

Freya grimaces. âThat doesn't make it less revolting.'

âA skua's got to eat. This is a tough place to stay alive.' He inspects the back of her poor head. âMan,' he remarks, clearly shocked by what must be a large lump sprouting from her skull. âThey copped you a beauty. Your induction to Antarctica; now you'll have something to write home about.'

He scans the clouds scudding by and gestures at their bikes. âThat's enough fun for one day. Time to drive the huskies home.'

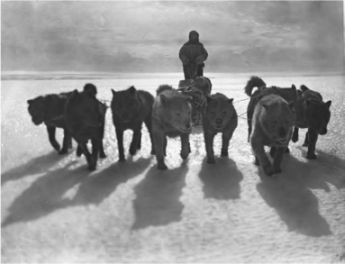

AS FREYA STEERS HER QUAD, the cold wind whistling through her helmet, she holds in her mind an image, not of Hurley but of Xavier Mertz kneeling in the snow with his camera as the dog team thundered toward him.

Time to drive the huskies home

.

Soft focus, atmospheric lighting, shadows from the dogs spilled across the snowâa Hurleyesque impression of nature.

Belgrave Ninnis and the

dogs taking a load of stores to

Aladdin's Cave.

Photographer Xavier Mertz,

1912.

Aladdin's Cave 1

August 1912

DOUGLAS, MADIGAN AND NINIS SPENT two days excavating an ice cave five and a half miles south of winter quarters, a sledging depot protected from weather, and a portal to the plateau. The crystalline walls glittered as though with a wealth of diamonds and within the magical cavern the three men discovered anew a world replete with silence. In the blizzard outside, the sledging dogs curled in on themselves, their matted hair frozen down, eight dark snouts barely visible above the snow.

Inside Aladdin's Cave, as Madigan and Ninnis dubbed it, colours looked dreamlike to Douglas, the luminescence in the ice casting an eerie veil of blue. The three ate quietly, unaccustomed to such a small company after living for so long with a hutful of eighteen, absorbing the absence of wind; in its place, though, their ears reverberated with an endless peal of ringing.

Douglas abhorred waste, but not even he could finish the boil-up of hoosh, so rich was the sledging porridge of dehydrated beef and lard pemmican, ground plasmon biscuit and glaxo milk powder all mixed to a slurry with boiling water.

A REPORT BOOMED FROM DEEP within the surrounding ice. Douglas lay facing Cecil Madigan's back in the three-man bag. The meteorologist's body was folded to a crook, his limbs awkward and muscles taut from unwanted intimacy. The heat generated by three bodies swaddled and lulled, rhyming breath soon giving way to sleep. Madigan's head sank back against Douglas's forearm, his hair coarse and dank against the silken reindeer pelt which exuded a trace of the Arctic tundra's earthy scent. Douglas wondered if the smell of a flesh-eating animal differed from that of a herbivore, if his own skin, like the others, oozed a disagreeable odour from a diet of penguin and seal.

A CANOPY OF MORNING CLOUD diffused the light and reduced the surface definition so at times he would step awkwardly into a trough, or catch his foot on a crest of sastrugi. Wind on the plateau had scoured the snow to concrete. He and Madigan took turns at running alongside the sledge, keeping on course dogs that loathed running into the bite of the wind. Before this trip the sum of dog sledging had been training circuits taken by Ninnis and Mertz. Now, on an uphill gradient and patches of slippery blue ice, the three menâbadly out of condition after a winter cooped up indoorsâstruggled to keep pace with the dog team. Douglas called for a rest and Ninnis, riding on the back of the sledge, planted his foot to push the brake's steel jaws into the snow. Dogs eased to a halt in snorts of steam.