The Nature of Ice (7 page)

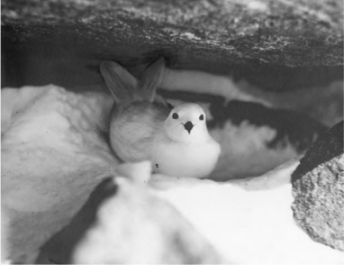

Nesting snow petrel

Composites

March 1912

THE CURIOUS NOISE PLAGUED DOUGLAS and Hurley all afternoon. Douglas thought of surf breaking incessantly on a distant beach; Hurley likened it to wind raking the tops of trees. To the west, flurries of snowdrift lifted from the cape while along the foreshore the bay remained still. Hurley had abandoned his tripod and lay sprawled on his belly among the rocky crevices, attempting to entice a nesting snow petrel to pose before his lens. He might score more than a photographic impression: the snow petrel's defence against intruders was an oily red concoction that the dainty little creature could summon from its belly and eject a full six feet.

Douglas rested on his haunches, framing with his eyes a panorama of the bay. The adélie rookery looked barely inhabited. The occasional weddell seal that still ventured ashore received a swift bullet to the head; scarlet snow lay in patches along the foreshore where Ninnis and Mertz butchered the meat while the dogs stood poised on their chains, fielding the scraps.

Ninnis and Mertz; their names rolled off the tongue as a couplet, never one without the other.

Hurley scrambled to his feet. âSomewhere up there, Doc,' he gestured to the sky, âit's blowing like the devil.'

Douglas gave a wry smile. âIf we could only find a way to make it stay up there.'

Throughout these last weeks the wind had blown with increased velocity, leaving only a few hours' reprieve before ratcheting up to blast the bay anew. This was their third month at winter quarters, the sum of their science work a boxful of specimens for the biological collection, and the daily meteorological and magnetic recordings. As for exploring further afield, blizzards had simply overwhelmed their attempts at preliminary sledging and trail-marking up on the plateau.

Hurley returned his camera to its tripod, entering his other world beneath the black cloth. Douglas looked forward to these hours more than he could say, assisting Frank with his eighty pounds of photographic equipment. Indoors, Hurley would act the eternal practical joker, but out here, camera in hand, he approached his art with scientific resolve. A seventy-mile-an-hour wind that blasted others indoors brought Hurley scurrying outside. He filmed men blown from the weather screen, photographed them hurricane walking, their bodies pitched semi-prone into the wind.

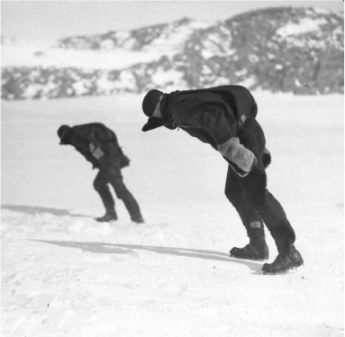

Photographing the blizzard

, Frank declared with utter certainty,

is our chance to show the world something it has

never seen before

.

Not so long ago, Douglas had believed a photographer was worthwhile solely as a means of recouping funds after the expedition: lantern slides to accompany public lectures, photographs to illustrate a book, an adventure cinematograph to be shown in theatres to the paying public. Yet he could see, from the prints Frank created in the hut's darkroom each evening, that his images stood alone. His photographs evoked two Antarctic worlds, one of serene, dazzling beauty, the other hostile and stark; each mood enkindled the senses. In his images of man against nature, one could come to believe in the presence of God. In the darkroom Hurley turned alchemist, pushing the limits of photographic science. For artistic effect he could take a scene of the bay photographed on an overcast day and merge it with a negative of a sky torn ragged with cloud.

Composites

, he called these compilations. No one but Hurley could detect the real from the embellished and even he, over time, might fail to distinguish between the two.

Oregon timber for the wireless masts stayed stacked beside the hut where it had lain since January. Oh, for a spell of calm long enough to get them up. By nowâthe evenings dim before nine o'clock, the receding sun as pale as tinned butterâthe relay station at Macquarie Island would be tuning in each night, listening unrewarded through an ether of static for a string of dots and dashes from a thousand miles south.

Douglas ran his thumb over a quartz seam in the gneiss painted with splashes of copper, crystals glowing emerald greenâminerals created deep within the earth's crust. Phenomenal forces of pressure and heat transformed silica-rich fluids into a bejewelled seam of rock. While it was the order of science that shaped his thoughts, this astonishing beautyâthe lustre of minerals, their exquisite crystal structures and kaleidoscope of colourâbewitched a deeper, intangible part of him.

The sound of moving air grew shrill. Hurley looked out from beneath his black cloth and stretched his arm to the sky as if to comb his fingers through a river of wind.

âSee here.' Douglas beckoned him, taking his handkerchief and polishing a film of sea salt from the quartz. âThis glassy green could be emerald, at the very least beryl; under a microscope we'd see a pattern of hexagonal prisms.'

Hurley kneeled down for a closer look. âJewels for a king.'

A willy-willy rose from the incline behind the hut, the funnel of snow wheeling across the slope like a child's spinning top.

âThis is green apatite.' Douglas brought their attention back to mineralogy. âAnd all of this,' he pointed, âis copper sulphide oxidised to malachite.' Douglas wanted Hurley to see the art in science as he saw the science in Hurley's photographic art. âThese minerals begin as separate elementsâcopper, beryllium, aluminium, phosphorous, calcium. The real magic happens when they crystallise and combine; then they transform into new minerals.'

âComposites.'

Douglas nodded. âNature's form of art.'

He caught the edge of a sound and turned to see a zinc sheet sweep into the air. It flew north over Boat Harbour like a great silver-backed gull then lifted higher again, the razor-sharp edge agleam as it twisted and turned, the sheet warbling a cry as it sailed overhead.

Hurricane walking

BY ELEVEN AT NIGHT THE BUILDINGS of Davis Station gleam from the golden light of a sun that, now, barely sets. Even Freya's accommodation block basks in the glow, the orange prefab box elevated by the lustre. Quiet hours; a reprieve, she thinks, pausing at the landing of her studio before stepping in.

Freya has resigned herself to her bone-shaking surrounds; she dons ear phones and edges up the volume of her iPod to muffle the shriek of engines, the drum-beats of air, anything to disguise the quaking that rattles the engineer's workshop below and reverberates upstairs. The two Squirrels, at rest now until morning, are lashed to the ground, rotor blades pulled taut so they bow like whale ribs.

She feels a visceral shiver when she opens the image attached to Marcus's email:

Hurricane walking. Autumn 1912

.

>> The diaries make constant reference to the appalling weather at winter quarters. By autumn they experienced winds exceeding 120 km per hour. Mawson's journal speaks of Frank Bickerton, the plane engineer, venturing out with Hurley and both being swept down a slope. Johnny Hunter, biologist, remarks of men being unable to walk upright, of the struggle to simply get underway against the wind resistance. Might this attached photo of Hurley's illustrate those diary excerpts?

Indeed it would. She draws back from the image of the two men and pictures the photographer clinging to his heavy wooden tripod, snow filling his camera as he battles wind and frostbite.

Freya wants to honour Hurley and his work, pay tribute to a pioneer of Antarctic photography. She knows that there are those who disparage Hurley's photographic vision, who claim his portraits reduced the men to members of a species battling nature's forces, rather than the heroes the public of the day wanted to see. Freya clicks to her own portraitsâher fellow trainees retrieving a quad bike from its simulated plunge through the sea ice during field training; scientists working in snowdrift at the tide gauge; Kittie changing the sunlight card, a parhelion filling the sky and tracing a circle around her. So far she has only a handful of images to place alongside Hurley's, yet she can see that the Antarctic environment itself is as vibrant now as it was then, as real and as complex as any human figure. In Hurley's

Hurricane Walking

, the identity of the two men was secondary to his desire to portray the challenge of working in such extremes. At winter quarters, the community of eighteen epitomised the hero, each man an integral part of a unified team. Descriptions from the diaries, Marcus has persuaded her, will add another layer to the photographic experience. Freya sits back further in her seat at the thought of all she owes her husband.

In preparing her second application to the Arts Council, try as she might she could not transform her creative vision onto paper, not in terms that Marcus found convincing. She agreed to his offer to collect impressions from Antarctic pioneers; he rewrote her proposal as

a narrative woven through

the photographic work

. Marcus found, in the diaries of the men from Douglas Mawson's 1911â14 expedition, the link to Australia's Antarctic historyâand to Hurleyâhe said her photographs needed.

Freya had whirled like a dervish from the letterbox to the house, delirious with joy at the Council's offer.

Come with me

, she had said to Marcus (hadn't she already anticipated his answer?)

Whatever will I do in Antarctica for five months?

Come as my assistant

, she'd offered lamely.

See the place.

Experience it with me.

Marcus had placed his arm around her shoulder.

I'll see ice

aplenty through your and Hurley's photos. I'm happy here, Freya,

working on the text.

FREYA RELISHES THESE QUIET AFTER-DINNER hours in her studio, a mug of hot chocolate warming her hands. If not for tomorrow's early startâshe is rostered on as slushy in the kitchenâshe would stay here half the night, would look up from her desk through the pane of crazed glass to gauge the lowest dip of light.

She pulls her studio door shut and registers a separate echo. Across the way she spies the figure of a man leaving the carpentry shop, hunched down: Chad McGonigal, head-chippie-turned-unwilling-photographic-assistant as of this morning's meeting with the station leader.

We've met

, Chad muttered without expression when Malcolm Ball introduced them. Freya studies his gait as he saunters down the roadway, jacket and overalls adding to his bulk, hands wedged in pockets, drawn in on himself as he had been throughout Malcolm's briefing.

He slows in his tracks, perhaps to take in the ice-choked bay flooded with pink. Does the wonder of the place fade in the eyes of a jaded man who's seen it countless times before? She watches him cross to the edge of the path and cartwheel through a bank of snow with a litheness that surprises her. When he stands and brushes snow from his hands, his long hair spills across his back.

Who deserves the most commiserationâa wounded Adam Singer, visibly put out at being denied the chance to help her; Chad McGonigal, landed an assignment he clearly doesn't want; or herself, the future of her project beholden to an unwilling man?

âJoy,' she bids the sky goodnight on her way down the steps.

THE MORNING WEATHER BALLOON RISES from the meteorological building, scudding across the sky faster than Freya can run. Cold air cuts her lungs and her hair is a tangled mess. She waves at Kittie and makes it to the kitchen just in time for her rostered day on.

Freya is not about to enquire of either chef why the second slushy hasn't shown up. The tension between Sandy and Tommo bulges like a pressure cooker lid about to explode. Enough to know that the tradies have downed tools for their morning break and are on their way, marching down the road. Among them are the nicotine hounds who peel away to the smoking shed for a longed-for drag, but the mass of hungry workers cascades into the dining room for ten o'clock smoko, mounding onto their plates a volume of food that leaves Freya wide-eyed.

More toast, slushy!

Freya slides the tray into a bain-marie of steaming porridge, beans, scrambled eggs, Sandy's maple syrup pancakes and his

grab-'em-while-they-last

cheese scones. No sooner has she topped up the coffee machine than there are empty jugs to refill. She scours the shelves in search of powdered milk, scans an out-of-reach ledge, afraid the chefs will snap at her if she asks, one more time, where things are kept. With a rising tide of despair she hears the clatter of pots being slung onto the bench, the sizzle of a pan plunged into water. Used baking tins hover in a teetering pile, tongs fall and clank, batter forms an ellipsis that stretches across the floor from the rim of the stove to a bowl bobbing in the sink.