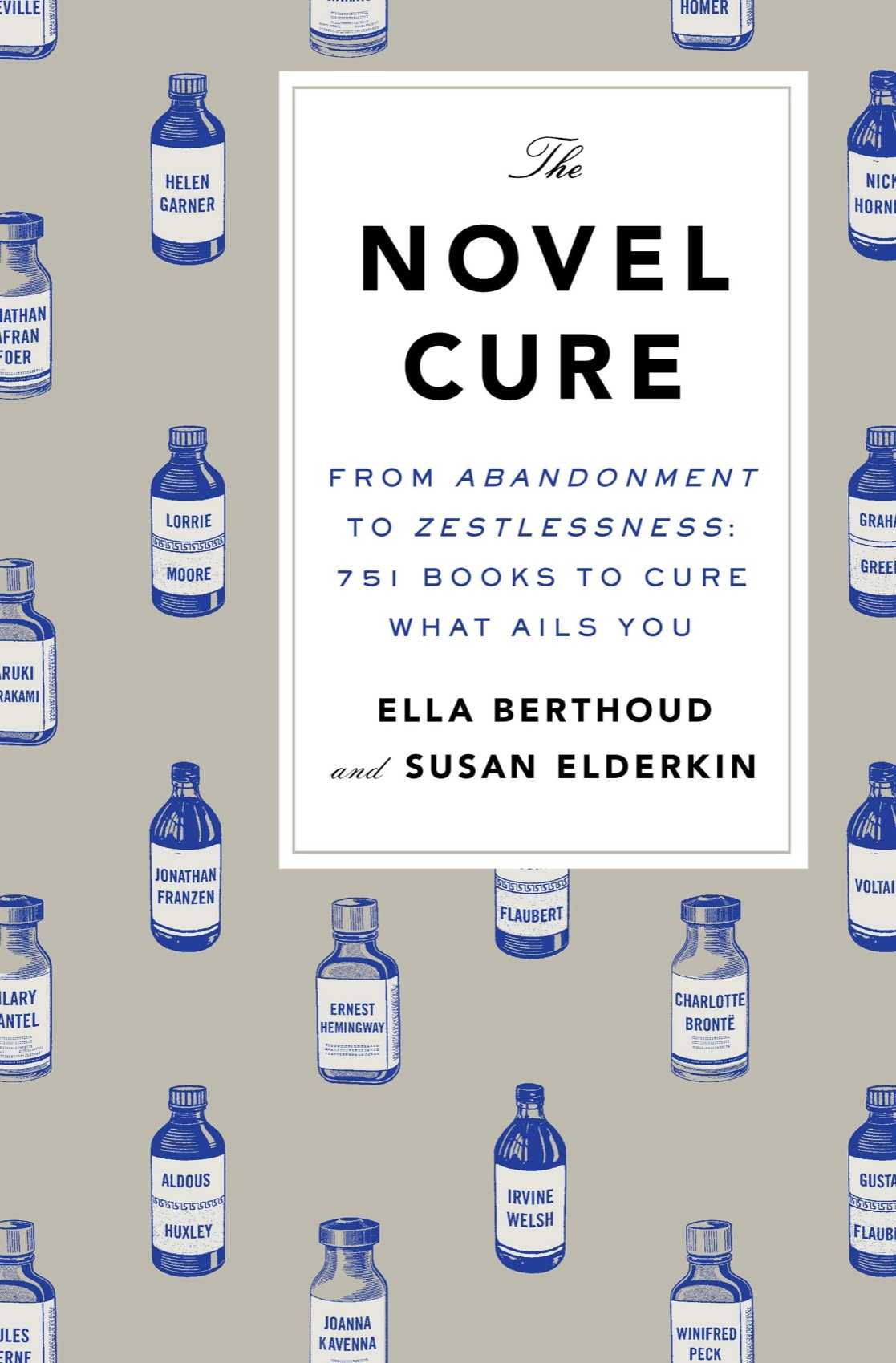

The Novel Cure: From Abandonment to Zestlessness: 751 Books to Cure What Ails You

Read The Novel Cure: From Abandonment to Zestlessness: 751 Books to Cure What Ails You Online

Authors: Ella Berthoud,Susan Elderkin

THE PENGUIN PRESS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA • Canada • UK • Ireland • Australia • New Zealand • India • South Africa • China

penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company

First published by The Penguin Press, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, 2013

Copyright © 2013 by Ella Berthoud and Susan Elderkin

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Berthoud, Ella.

The novel cure : from abandonment to zestlessness: 751 books to cure what ails you / Ella Berthoud and Susan Elderkin.

pages cm

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-101-63875-0

1. Fiction—History and criticism—Theory, etc. 2. Reading, Psychology of. 3. Bibliotherapy. 4. Best books. I. Elderkin, Susan. II. Title.

PN3352.P7B47 2013

809.3’9353—dc23 2013017177

To Carl and Ash

and in memory of Marguerite Berthoud and David Elderkin,

who taught us to love books—and build the bookshelves

One sheds one’s sicknesses in books—repeats and presents again one’s emotions, to be master of them.

—D. H. LAWRENCE

(The Letters of D. H. Lawrence)

Introduction

AILMENTS A TO Z

Acknowledgments

Reading Ailments Index

Ten-Best Lists Index

Author Index

Novel Title Index

bib·lio·ther·a·py

noun

\bi-ble---'ther--pe-, -'the-r-py

: the prescribing of fiction for life’s ailments

—Berthoud and Elderkin, 2013

T

his is a medical handbook—with a difference.

First of all, it does not discriminate between emotional pain and physical pain—you’re as likely to find a cure within these pages for a broken heart as a broken leg. It also includes common predicaments you might find yourself in, such as moving house, looking for Mr. or Mrs. Right, or having a midlife crisis. Life’s bigger challenges, such as losing a loved one or becoming a single parent, are in here too. Whether you’ve got the hiccups or a hangover, a fear of commitment or a sense of humor failure, we consider it an ailment that deserves a remedy.

But there’s another difference too. Our medicines are not something you’ll find at the drugstore, but at the bookshop, in the library, or downloaded onto your electronic reading device. We are bibliotherapists, and the tools of our trade are books. Our apothecary contains Balzacian balms and Tolstoyan tourniquets, the salves of Saramago and the purges of Perec and Proust. To create it, we have trawled two thousand years of literature for the most brilliant minds and restorative reads, from Apuleius, second-century author of

The Golden Ass

, to the contemporary tonics of Ali Smith and Jonathan Franzen.

Bibliotherapy has been popular in the form of the nonfiction self-help book for several decades now. But lovers of literature have been using novels as salves—either consciously or subconsciously—for centuries. Next time you’re feeling in need of a pick-me-up or require assistance with an emotional tangle, reach for a novel. Our belief in the effectiveness of fiction as

the purest and best form of bibliotherapy is based on our own experience with patients and bolstered by an avalanche of anecdotal evidence. Sometimes it’s the story that charms; other times it’s the rhythm of the prose that works on the psyche, stilling or stimulating. Sometimes it’s an idea or an attitude suggested by a character in a similar quandary or jam. Either way, novels have the power to transport you to another existence and see the world from a different point of view. When you’re engrossed in a novel, unable to tear yourself from the page, you are seeing what a character sees, touching what a character touches, learning what a character learns. You may

think

you’re sitting on the sofa in your living room, but the important parts of you—your thoughts, your senses, your spirit—are somewhere else entirely. “To read a writer is for me not merely to get an idea of what he says, but to go off with him and travel in his company,” said André Gide. No one comes back from such a journey quite the same.

Whatever your ailment, our prescriptions are simple: a novel (or two), to be read at regular intervals. Some treatments will lead to a complete cure. Others will simply offer solace, showing you that you are not alone. All will offer the temporary relief of your symptoms due to the power of literature to distract and transport. Sometimes the remedy is best taken as an audiobook, or read aloud with a friend. As with all medicines, the full course of treatment should always be taken for best results. Along with the cures, we offer advice on particular reading issues, such as being too busy to read or what to read when you can’t sleep, along with the ten best books to read in each decade of life; and the best literary accompaniments for important rituals or rites of passage, such as being on vacation—or on your deathbed.

*

We wish you every delight in our fictional plasters and poultices. You will be healthier, happier, and wiser for them.

ABANDONMENT

Plainsong

KENT HARUF

I

f inflicted early, the effects of physical or emotional abandonment—whether you were left by too busy parents to bring yourself up, told to take your tears and tantrums elsewhere, or off-loaded onto another set of parents completely (see: Adoption)—can be hard to shrug. If you’re not careful, you might spend the rest of your life expecting to be let down. As a first step to recovery, it is often helpful to realize that those who abandon you were most likely abandoned themselves. And rather than wishing they’d buck up and give you the support or attention you yearn for, put your energy into finding someone else to lean on who’s better equipped for the job.

Abandonment is rife in

Plainsong

, Kent Haruf’s account of small-town life in Holt, Colorado. Local schoolteacher Guthrie has been abandoned by his depressed wife, Ella, who feigns sleep when he tries to talk to her and looks at the door with “outsized eyes” when he leaves. Their two young sons, Ike and Bobby, are left bewildered by her unexplained absence from their lives. Old Mrs. Stearns has been abandoned by her relatives, either through death or neglect. And Victoria, seventeen years old and four months’ pregnant, is abandoned first by her boyfriend and then by her mother, who, in a backhanded punishment to the man who’d abandoned them both many

years before, tells her, “You got yourself into this, you can just get out of it,” and kicks her out of the house.

Gradually, and seemingly organically—although in fact it is mostly orchestrated by Maggie Jones, a young woman with a gift for communication—other people step into the breach. Most astonishing are the McPheron brothers, a pair of “crotchety and ignorant” cattle-farming bachelors who agree to take the pregnant Victoria in: “They looked at her, regarding her as if she might be dangerous. Then they peered into the palms of their thick callused hands spread out before them on the kitchen table and lastly they looked out the window toward the leafless and stunted elm trees.” The next thing we know they are running around shopping for cribs, and the rush of love for the pair felt by Victoria, as well as the reader, transforms them overnight. As we watch the community quicken to its role as extended family—frail Mrs. Stearns teaching Ike and Bobby to make cookies, the McPherons watching over Victoria with all the tender, clumsy tenacity they normally reserve for their cows—we see how support can come from very surprising places.

If you have been abandoned, don’t be afraid to reach out to the wider community around you—however little you know its inhabitants as individuals. They’ll thank you for it one day.

True History of the Kelly Gang

PETER CAREY

I

f you’re accused of something and you know you’re guilty, accept your punishment with good grace. If you’re accused and you didn’t do it, fight to clear your name. And if you’re accused and you know you did it but you don’t think what you did was wrong, what

then

?

Australia’s Robin Hood, Ned Kelly—as portrayed by Peter Carey in

True History

of the Kelly Gang

—commits his first crime at ten years old when he kills a neighbor’s heifer so his family can eat. The next thing he knows, he’s been apprenticed (by his own mother) to the bushranger, Harry Power. When Harry robs the Buckland Coach, Ned is the “nameless person” who blocked the road with a tree and held the horses so “Harry could go about his trade.” And thus Ned’s fate is sealed: He’s an outlaw forever. He makes something glorious of it.

In his telling of the story—which he has written down in his own words for his baby daughter to read one day, knowing he won’t be around to tell her himself—Ned seduces us completely with his rough-hewn, punctuation-free prose that bounds and dives over the page. But what really warms us to this Robin Hood of a boy/man is his strong sense of right and wrong: Ned is guided at all times by a fierce loyalty and a set of principles that happen not to coincide with those of the law. When his ma needs gold, he brings her gold; when both his ma and his sister are deserted by their faithless men, he’ll “break the 6th Commandment” for their sakes. And even though Harry and his own uncles use him “poorly,” he never betrays them. How can we not love this murdering bushranger with his big heart? It is the world that’s corrupt, not him, and we cheer and whoop from the sidelines as pistols flash and his Enfield answers. And so the novel makes outlaws of its readers.

Ned Kelly is a valuable reminder that just because someone has fallen foul of society’s laws, he’s not necessarily bad. It’s up to each one of us to decide for ourselves what is right and wrong in life. Draw up your personal constitution, then live by it. If you step out of line, be the first to give yourself a reprimand. Then see: Guilt.

See:

Alcoholism

See:

Coffee, can’t find a decent cup of

See:

Drugs, doing too many

See:

Gambling

See:

Sex, too much

See:

Shopaholism

See:

Internet addiction

See:

Smoking, giving up

The Catcher in the Rye

J. D. SALINGER

• • •

Who Will Run the Frog Hospital?

LORRIE MOORE

• • •

In Youth Is Pleasure

DENTON WELCH

H

ormones rage. Hair sprouts where previously all was smooth. Adam’s apples bulge and voices crack. Acne erupts. Bosoms bloom. And hearts—and loins—catch fire with the slightest provocation.

First, stop thinking you’re the only one it’s happened to. Whatever you’re going through, Holden Caulfield got there first. If you think everything is “lousy,” if you can’t be bothered to talk about it, if your parents would have “two hemorrhages apiece” if they knew what you were doing right now, if you’ve ever been expelled from school, if you think all adults are phonies, if you drink/smoke/try to pick up people much older than you, if your so-called friends are always walking out on you, if your teachers tell you you’re letting yourself down, if the only person who understands you is your ten-year-old sister, if you protect yourself from the world with your swagger, your bad language, your seeming indifference to whatever happens to you next—if any of these is true for you,

The Catcher in the

Rye

will carry you through.

Adolescence can’t be cured, but there are ways to make the most of it. Lorrie Moore’s

Who Will Run the Frog Hospital?

is full of the usual horrors. The narrator, Berie, is a late developer who hides her embarrassment by mocking her “fried eggs” and “tin cans run over by a car,” and she and her best friend, Sils, roll about laughing when they remember how Sils once tried to shave off her pimples with a razor. In fact, laughing is something they do a lot of together—and they do it “violently, convulsively,” with no sound coming out. They also sing songs together—anything from Christmas carols to TV theme tunes

and Dionne Warwick. And we applaud that they do. Because if you don’t sing loudly and badly with your friends when you’re

fourteen and fifteen, letting the music prepare your heart for “something drenching and big” to come, when do you get to do it?

A teenage boy who makes no friends at all yet lives with incredible intensity is Orvil Pym in Denton Welch’s

In Youth Is Pleasure

. This beautifully observed novel, published in 1945, takes place over the course of one languid summer against the backdrop of an English country hotel, where Orvil, caught in a state of pubescent confusion, holidays with his father and brothers. Aloof and apart, he observes the flaws in those around him with a pitiless lens. He explores the countryside, guiltily tasting the communion wine in a deserted church, then falling off his bike and crying in despair for “all the tortures and atrocities in the world.” He borrows a boat and rows down a river, glimpsing two boys whose bodies “glinted like silk” in the evening light. New worlds beckon, just beyond his reach, as he hovers on the edge of revelation. And for a while, he considers pretending to be mad, to avoid the horrors awaiting him back at school. Gradually he realizes that he cannot leap the next ten years—that he just has to survive this bewildering stage and behave in “the ordinary way,” smiling and protecting his brothers’ pecking order by hiding his wilder impulses.