The novels, romances, and memoirs of Alphonse Daudet (13 page)

Read The novels, romances, and memoirs of Alphonse Daudet Online

Authors: 1840-1897 Alphonse Daudet

The most pressing thing was to see Roger; with one bound I reached his room, but nobody was there. "Very well," I said to myself; "he must have gone over to the Cafe Barbette," and in such dramatic circumstances this caused me no surprise.

At the Caf6 Barbette, too, I found nobody. " Roger," they told me, " had gone off to the Meadow with the non-commissioned officers." What the devil could they be doing there in such weather? I began to be extremely uneasy, so, refusing an invitation to play billiards, I turned up my trousers at the bottom, and rushed out into the snow, in the direction of the Meadow, to look for my good friend the fencing-master.

CHAPTER XII.

THE IRON RING.

It is a good mile and a quarter from the gates of Sarlande to the Meadow; but, at the rate at which I was going, on that day, I covered the ground in less than a quarter of an hour. I trembled for Roger. I feared lest the poor fellow, in spite of his promise, might have told everything to the principal during the study-hour; it seemed to me that I still saw the butt of his pistol shine. This lugubrious thought lent me wings.

However, as I went along, I could see in the snow the trace of numerous footsteps going toward the Meadow, and it reassured me somewhat to think that the fencing-master was not alone.

Then, slackening my pace, I thought of Paris, Jacques, and my departure. But, after a minute, my terrors began again.

" Roger is evidently going to kill himself. Why otherwise should he come to this deserted place, far from the town ? If he has taken his friends from the Cafe Barbette with him, it must be to say good-by to them, to drink the stirrup-cup, as they say. Oh, those soldiers! " And I set off again at breathless speed.

Luckily, I was approaching the Meadow, and could already see the tall trees laden with snow. " My poor friend," said I to myself, " if I only arrive in time ! "

The footsteps led me thus as far as a public-house known as the Esperon.

This public-house was a suspicious place of bad reputation, where the rakes of Sarlande had their pleasure-parties. I had been there more than once in the company of the noble fellows, but I had never thought its appearance so sinister as on that day. Yellow and dirty, in the midst of the immaculate whiteness of the plain, with its low door, ruinous walls and ill-washed window-panes, it was skulking behind a grove of small elms. The little house looked ashamed of its ugly trade.

As I approached, I heard a merry noise of voices, laughter, and the clash of glasses.

" Good God," thought I, with a shudder, " it is the stirrup-cup." And I stopped to take breath.

I had reached the back of the public-house; I pushed open the latticed door, and entered the garden. What a garden! A big bare hedge, clumps of leafless lilac bushes, heaps of refuse lying on the snow, and white arbors that looked like Esquimaux' huts. It was dreary enough to make one cry.

The racket came from a room on the ground-floor, and the men must have grown hot from drinking, for, in spite of the cold, they had opened both windows wide.

I had already put my foot on the first step,

when I heard something that stopped me short and made my blood run cold; it was my own name pronounced amid great bursts of laughter. Roger was speaking of me, and, strange to say, every time the name Daniel Eyssette recurred, the others laughed to split their sides.

Impelled by a painful curiosity, and feeling sure that I was about to learn something extraordinary, I drew back, and without being heard by anybody, thanks to the snow, which, like a carpet, deadened the sound of my steps, I slipped into one of the arbors, that was conveniently situated, right underneath the windows.

I shall see that arbor all my life long; I shall see all my life the green mould that lined it, its untidy, muddy floor, its little green-painted table, and its wooden benches dripping with water. The light hardly penetrated through the snow that was piled upon the roof and, slowly melting, fell drop by drop on my head.

It was there, there in that arbor, dark and cold as a tomb, that I learned how wicked and base men can be ; it was there I learned to doubt, scorn and hate. You that read, God forbid that you should ever enter that arbor! I stood upright, holding my breath, and, red with anger and shame, listened to what they were saying at the Esperon.

My good friend the fencing-master, was addressing the others. He related the adventure of Cecilia, the story of the love-letters, the visit of the sub-prefect to the school, with embellishments

In the Arbor

Capyriyhe, iBg^. i^Zitdt>. Pyr<,7

and gestures, to judge from the transports of his audience.

" You understand, my little loves," said he in his jeering tone, " it was not for nothing that I acted comedy for three years at the Zouave theatre. As true as I tell you, I believed for one moment that the game was lost, and I thought I should never come again to drink old Esperon's good wine with you. Little Eyssette had told nothing, it is true ; but there was still time for him to speak ; and, between ourselves, I believe he wanted only to leave me the honor of denouncing myself. So I said : * Look sharp, Roger, and bring on the grand scene.'"

Thereupon my good friend the fencing-master, began to act what he called the grand scene, that is to say what had passed between him and me in my room in the morning. Ah, the wretch ! He forgot nothing. He cried : " My mother, my poor mother! " with a theatrical intonation, and then imitated my voice: " No, Roger, no, you shall not go! " The grand scene was really comic in the highest degree, and all the audience rolled in their chairs with laughing. As to me, I felt the big tears running down my cheeks; I shivered and my ears rang. I divined all the odious comedy of the morning, and vaguely understood that Roger had purposely scjit my letters so as to protect himself against any mishap; that his mother, his poor mother, had been dead for twenty years; and that I had taken his pipe-case for the butt-end of a pistol.

9

"And how about the lovely Cecilia?" asked one of the noble fellows.

" Cecilia told no tales; she packed her trunks, for she is a good girl."

" And little Daniel ? What will become of him?"

" Bah ! " answered Roger.

Here there was a gesture that made everybody laugh.

This burst of laughter put me beside myself. I wanted to come out of the arbor and appear suddenly in the midst of them like a spectre. But I contained myself: I had already been ridiculous enough.

The roast was brought in, and they clinked glasses.

" Here 's to Roger! To Roger! " they cried.

I could stand it no longer, I was too miserable. Without troubling myself lest I should be seen, I rushed through the garden, cleared the latticed gate at a bound, and began to run straight ahead like a madman.

Night was silently falling, and in the dusk of the twilight, the immense field of snow took on an indescribable aspect of profound melancholy.

I ran thus for some time like a wounded deer; and if hearts that break and bleed were anything except expressions used by poets, I swear that a long trail of blood might have been found behind me on the white plain.

I knew I was ruined. How should I get money? How should I go away? How should I

reach my brother Jacques? It would not help me to denounce Roger; he could deny everything, now that Cecilia was gone.

At last, exhausted and overpowered by fatigue and grief, I let myself fall down in the snow at the foot of a chestnut tree. I might have stayed there till next day, perhaps, crying, and without power to think, when all at once, very, very far away, in Sarlande, I heard a bell ring. It was the school bell. I had forgotten everything, but this bell called me back to life: I had to return and superintend the boy's play-hour in the hall. In thinking of the hall, a sudden idea struck me. My tears stopped immediately, and I felt stronger and calmer. I rose, and, with the deliberate step of a man who has just made an irrevocable decision, continued my way to Sarlande.

If you care to know the irrevocable decision Little What 's-His-Name had made, follow him to Sarlande across the great white plain; follow him through the sombre, muddy streets of the town ; follow him into the vestibule of the school; follow him into the hall during the play-hour, and remark with what singular persistence he stares at the big iron ring suspended in the middle of the room; and when the play-hour is over, follow him to the school-room, go up the steps to his seat with him, and read over his shoulder this painful letter that he is engaged in writing, in the midst of the hubbub raised by the noisy children:

Monsieur Jacques Eyssette,

Rue Bonaparte, Paris;

Forgive me, my beloved Jacques, the sorrow I cause you. You, who no longer weep, I am about to make weep again; but it will be the last time, I promise you. When you receive this letter your poor Daniel will be dead.

Here the uproar in the school-room is redoubled ; Little What's-His-Name stops to distribute a few penalties right and left, gravely and without anger. Then he continues:

Do you see, Jacques, I was too miserable. I could not do otherwise than kill myself. My future is ruined; I am driven away from the school, — it is a story about a woman, too long to tell you ; then I am in debt; I no longer know how to work; I am ashamed, I am weary, disgusted, and life terrifies me. I should rather go.

Little What's-His-Name is obliged to stop again. " Five hundred lines for Soubeyrol! Fouque and Loupi will be kept in on Sunday." After this, he finishes his letter:

Good-bye, Jacques. There is much more that I want to say to you, but I feel that I shall cry, and the boys are watching me. Tell Mamma that I slipped from the top of a cliff, on a walk, or that I was drowned skating. Invent any story you choose, but never let the poor woman know the truth. Kiss my dear mother many times for me; kiss my father, too, and try soon to rebuild a beautiful hearth for them. Good-bye ; I love you. Remember Daniel.

The letter ended, Little What 's-His-Name begins another conceived thus:

Monsieur l'Abb^, — I beg you to see that the letter I leave for my brother Jacques be sent to him. At the same time please cut off my hair and make a little package of it for my mother.

I beg your pardon for the pain I give you. I killed myself because I was too unhappy here. You alone, Monsieur I'Abbe, have always shown kindness to me. I thank you for it.

Daniel.

After this, Little What 's-His-Name puts this letter and the one for Jacques into one large envelope, with this superscription: "The person who first finds my body is requested to give this letter into the Abbe Germane's hands." Then, having attended to all his afTairs, he waits quietly for the end of the study-hour.

The study-hour is over. First, they have supper, then prayers, and all go up to the dormitory.

The boys go to bed ; Little What 's-His-Name walks up and down, waiting for them to fall asleep. Here is M. Viot, making his rounds; the mysterious clank of his keys is to be heard, and the mufifled sound of his slippers on the floor. " Goodnight, M. Viot," murmurs Little What 's-His-Name. " Good-night, sir," answers the inspector, in a low voice; then he goes away, and his steps are lost in the corridor.

Little What's-His-Name is alone. He opens the door softly, and stops a moment on the land-

ing to see if the boys are not going to wake up; but all is quiet in the dormitory.

Then he goes downstairs, and slips along on tiptoe in the shadow of the walls. The north wind blows drearily through the cracks underneath the doors. At the foot of the staircase, passing in front of the peristyle, he sees the court-yard white with snow, lying within the four big dark school-buildings.

Up there, near the roof, a lamp is burning; it is the Abbe Germane at work upon his great book. From the bottom of his heart, Little What's-His-Name sends a last and most sincere farewell to the good Abbe; then he enters the hall.

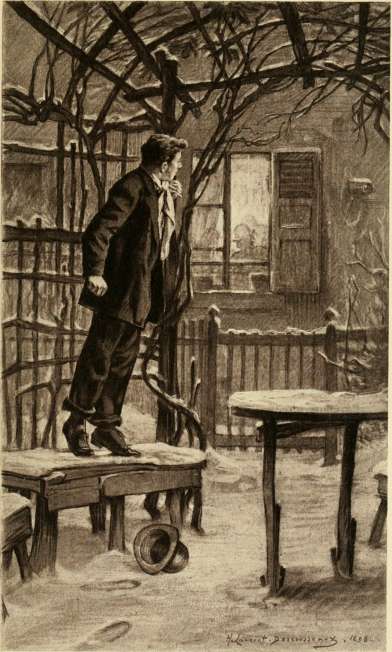

The old gymnasium of the naval academy is filled with cold and sinister shadow. A little moonlight falls through the grated window, and strikes full upon the big iron ring, — oh, that ring! Little What 's-His-Name has done nothing but think of it for hours, — upon the big iron ring that shines like silver. In a corner of the hall, an old stool had long been lying about unnoticed. Little What's-His-Name goes and gets it, carries it under the ring, and mounts upon it; he was not mistaken, it is just the proper height. Then he undoes his cravat, a long cravat of violet silk that he wears tied round his neck like a ribbon. He attaches the cravat to the ring, and makes a slip-noose. One o'clock strikes. Come, it is time to die. With trembling hands Little What 's-His-Name pulls open the slip-noose; a sort of delirium carries

him away. Good-bye, Jacques; good-bye, Mme. Eyssette.

Suddenly an iron hand grasps him. He feels himself seized round the middle, lifted from the stool, and set down on his feet upon the ground. At the same time a harsh, satirical voice that he knows well, says:

" This is an idea, to try the trapeze at such time of night! "

Little What's-His-Name turns in amazement.