The ode less travelled: unlocking the poet within (11 page)

Incidentally, Vladimir Nabokov in his

Notes on Prosody

is very unkind about calling these effects ‘substitutions’–he prefers to call a pyrhhic substitution a ‘scud’ or ‘false pyrrhic’ and a trochaic substitution a ‘tilted scud’ or ‘false trochee’. I am not sure this is any clearer, to be honest.

Anyway, you might have spotted that this trick, this trope, this ‘downgrading’ of one accent, has the effect of drawing extra attention to the following one. The next strong iambic beat, the

own

has

all the more emphasis

for having followed three unstressed syllables.

If the demotion were to take place in the

fourth

foot it would emphasise the

last

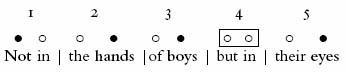

beat of the line, as in this pyrrhic substitution in Wilfred Owen’s ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’, which as it happens also begins with a

trochaic

switch. R

EAD IT OUT LOUD:

Both the excerpts above contain pyrrhic substitution, Shakespeare’s in the third foot, Owen’s in the fourth. Both end with the word ‘eyes’, but can you see how Shakespeare’s use of it in the

third

foot causes the stress to hammer harder down on the word

own

and how Owen’s use of it in the

fourth

really pushes home the emphasis on

eyes

? Which, after all, is the point the line is making,

not

in their hands, but in their

eyes

. (Incidentally, I think the trochaic substitution in the first foot also helps emphasise ‘hands’. Thus, when read out, the line contrasts hands and eyes with extra emphasis.)

Owen’s next line repeats the pyrrhic substitution in the same, fourth, foot.

Shall shine the holy glimmers of good-byes.

A stressed

of

would be a horrid example of what’s called a

wrenched accent

, an unnatural stress forced in order to make the metre work: scudding over the ‘of’ and making the foot pyrrhic does not sacrifice the metre.

Owen was a poet who, like Shakespeare,

really knew what he was doing

. These effects are not accidental, the substitutions do not come about by chance or through some carefree inability to adhere to the form and hoping for the best. Owen studied metre and form constantly and obsessively, as did Keats, his hero, as indeed did all the great poets. They would no more be

unaware

of what they were doing than Rubens could be unaware of what he was doing when he applied an impasto dot of white to give shine to an eye, or than Beethoven could be unaware of what happened when he diminished a seventh or syncopated a beat. The freedom and the ease with which a master can do these things belies immense skill derived from practice.

Incidentally, when Rubens was a young man he went round Rome feverishly drawing and sketching antique statues and Old Master paintings, lying on his back, standing on ladders, endlessly varying his viewpoint so as to give himself differing angles and perspectives. He wanted to be able to paint or draw any aspect of the human form from any angle, to master foreshortening and moulding and all the other techniques, spending months on rendering hands alone. All the great poets did the equivalent in their notebooks: busying themselves endlessly with different metres, substitutions, line lengths, poetic forms and techniques. They wanted to master their art as Rubens mastered his. They say that the poet Tennyson knew the

quantity

of every word in the English language except ‘scissors’. A word’s quantity is essentially the sum of the duration of its vowels. We shall come to that later. The point is this: poetry is all about

concentration

, the concentration of mind and the concentration of thought, feeling and language into words within a rhythmic structure. In normal speech and prose our thoughts and feelings are

diluted

(by stock phrases and roundabout approximations); in poetry those thoughts and feelings can be, must be,

concentrated

.

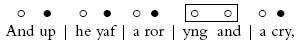

It may seem strange for us to focus in such detail on something as apparently piffling as a pyrrhic substitution, but I am convinced that a sense, an awareness, a familiarity and finally a mastery of this and all the other techniques we have seen and will see allow us a confidence and touch that the uninformed reading and writing of verse could never bestow. It is a little like changing gear in a car: it can seem cumbersome and tricky at first, but it soon becomes second nature. It is all about developing the poetic equivalent of ‘muscle memory’. With that in mind, here are some more lines featuring these stress demotions or pyrrhic substitutions. I have boxed the first two examples and explained my thinking. Here is one from the Merchant’s Tale:

You would not say ‘a roaring

AND

a cry’ unless the sense demanded it. Chaucer, like Owen, shows that a demotion of the

fourth

beat throws more weight on to the fifth:

CRY

. Owen demonstrates that it is possible with the second beat too.

‘Come gargling

from

the froth-corrupted lungs’ seems a bit wrenched. The demotion allows the push here on ‘garg’ and ‘froth’ to assume greater power: ‘Come

garg

ling from the

froth

-cor

rupt

ed

lungs

’.

Look at these lines from a poem that every American schoolchild knows: ‘Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening’, by Robert Frost. It is the literary equivalent of ‘The Night Before Christmas’, quoted and misquoted every holiday season in the States:

The

woods

are

love

ly,

dark

, and

deep

,

But

I

have

pro

mises to

keep

,

And

miles

to

go

be

fore

I

sleep

,

To read the phrase ‘

pro

mi

sés

to

keep

’ would be an absurd wrench, wouldn’t it? Clearly that’s a pyrrhic substitution too.

The opening line of Shakespeare’s

Richard III

has a demoted third beat: note that the first line begins with a trochaic substitution:

Now

is the

win

ter of our

dis

con

tent

So here is a summary of the six new techniques we’ve learned to enrich the iambic pentameter.

- 1. End-stopping: how the sense, the thought, can end with the line.

- 2. Enjambment: how it can run

through

the end of a line. - 3. Caesura: how a line can have a break, a breath, a pause, a gear change.

- 4. Weak endings: how you can end the line with an extra, weak syllable.

- 5. Trochaic substitution: how you can

invert

the iamb to make a trochee. - 6. Pyrrhic substitution: how you can

downgrade

the beat of an interior (second, third or fourth) foot to turn it into a doubly weak or

pyrrhic

foot.

Poetry Exercise 4

You can probably guess what I’m going to ask for here. Sixteen unrhymed lines of iambic pentameter. The idea is to use pyrrhic and trochaic substitutions (five points for each), weak endings–that extra syllable at the end (two points for each) but all without going overboard and losing the primary iambic rhythm. You can also award yourself two points for every successful enjambment.

Before you embark upon your own, we are going take a look at and mark my attempt at the exercise. I have sought inspiration, if that is the word, from the headlines on today’s BBC news website and would recommend this as preferable to staring out of the window chewing the end of a pencil awaiting the Muse’s kiss. Four news stories in all.

Policemen, in a shocking poll revealed

They have no time for apprehending felons

Criminals now at last are free to work.

Why can’t the English play the game of cricket?

Inside a tiny wooden urn are buried

The Ashes of a great and sporting nation.

19

Babies are now available in female

Or male. Hard to decide which sex I’ll pick.

Maybe I’ll wait till gender is redundant.

Towards the middle of a mighty ocean

Squats a forgotten island and its people;

The sea that laps the margins of the atoll

Broadcasts no mindless babble on its waves;

No e-mail pesters the unsullied palm groves

Newspaper stories pass it quietly by.

How long before we go there and destroy it?

I know. Pathetic, isn’t it? I hope you are filled with confidence. Once again, I must emphasise, these are no more poems than practise scales are sonatas. They are purely exercises, as yours should be. Work on solving the problems of prosody, but don’t get hung up about images, poetic sensibility and word choices. The lines and thoughts should make sense, but beyond that doggerel is acceptable.

G

ET YOUR PENCIL OUT

and mark the metre in each line of my verses. It should be fairly clear when the line starts with a trochee, but pyrrhics can be more subjective. I shall do my marking below: see if you agree with me.

P

for a pyrrhic substitution,

T

for a trochaic.

H

for hendecasyllable (or for hypermetric, I suppose).

E

is for enjambment.