The ode less travelled: unlocking the poet within (42 page)

Parenthesis proud, bracket-bold, happiest with hyphens

The writers stagger intoxicated by terms, adjective-unsteadied–

Describing in graceless phrases fizzling like soda siphons

All things crisp, crunchy, malted, tangy, sugared and shredded.

Parodies are rife in popular culture, a staple of television comedy, but literary and verse parodies seem to have fallen from fashion, Wendy Cope being one of the few practising poets who plays happily and fruitfully with the style of other poets. Now it’s your turn.

Poetry Exercise 17

I am sure you have a favourite poet. Write a parody of their style and prosodic manner. Try and make it comically inappropriate: if you like Ted Hughes, try writing a fearsome, physically tough description of a Barbie doll or something else very un-Hughesy. I know this is a bit of a

Spectator

Competition sort of exercise, but it is a good way of noticing all the metrical, rhyming and formal mannerisms of a poet. If you are really feeling bold, try writing a cento. You will need the collected works of the poet you choose, otherwise a cento mixing different verses from an anthology might be worth trying. Surprise yourself.

IX

Exotic Forms

15

Haiku—senryu–tanka–ghazal–luc bat–tanaga

H

AIKU

Five seven and five:

Seventeen essential oils

For warm winter nights.

The

HAIKU

, as you may already know, is a three-line poem of Japanese origin whose lines are composed of five, seven and five syllables. There is much debate as to whether there is any purpose to be served in English-language versions of the form. Those who understand Japanese are strong in their insistence that haikus in our tongue are less than a pale shadow of the home-grown original. English, as a

stress

-timed language, cannot hope to reproduce the effects of

syllable

-timed Japanese. I define these terms (rather vaguely) in the section on Syllabic Verse in Chapter One.

Just so that you are aware, there is a great deal more to the haiku than mere syllable count. For one thing, it is considered

de rigueur

to include the season of the year, if not as crassly as mine does, then at least by some other reference to weather or atmosphere, what is known as a

kigo

word. A reverence for life and the natural world is another apparent sine qua non of the form, the aim being to provide a kind of aural, imagistic snapshot (a

shasei

or ‘sketch of nature’). The senses should be engaged and verbs be kept to a minimum, if not expunged entirely. The general tenor and thrust of the form (believe me, I am no expert) seems to be for the poet (

haijin

) to await a ‘haiku moment’, an epiphany or imaginative inspiration of some kind. The haiku is a distillation of such a moment. In their native land haikus are written in one line, which renders the idea of a 5–7–5 syllable count all the more questionable. They also contain many puns (

kakekotoba

), this not being considered a groan-worthy practice in Japanese. A caesura, or

kireji

, should be felt at the end of either the first or second ‘line’.

Haiku descends from

haikai no renga

, a (playful) linked verse development of a shorter form called

waka

. The haikai’s first stanza was called a

hokku

and when poets like Masaoka Shiki developed their new, stand-alone form in the nineteenth century, they yoked together the words

haikai

and

hokku

to make

haiku

. We now tend to backdate the term and call the short poems of seventeenth-century masters such as Matsuo Basho

haikus

, although they ought really to be called

hokkus

. Clear?

A haiku which does not include a

kigo

word and is more about

human

than

physical

nature is called a

SENRYU

which, confusingly, means ‘river willow’.

Those who have studied the form properly and write them in English are now very unlikely to stick to the 5–7–5 framework. The Japanese

on

(sound unit) is very different from our syllable and most original examples contain far fewer words than their English equivalents. For some the whole enterprise is a doomed and fatuous mismatch, as misguided as eating the Sunday roast with chopsticks and calling it sushi. Nonetheless non-Japanese speakers of some renown have tried them. They seemed to have been especially appealing to the American beat poets, Ginsberg, Ferlinghetti, Corso and Kerouac, as well as to Spanish-language poets like Octavio Paz and Jorge Luis Borges. Here are a couple of Borges examples (it is possible that haikus in Spanish, which like Japanese is syllabically timed, work better than in English)–my literal translations do not obey the syllabic imperatives.

La vasta noche

no es ahora otra cosa

que una fragancia.

(The enormous night

is now nothing more

than a fragrance.)

Callan las cuerdas.

La música sabía

lo que yo siento.

(The strings are silent.

The music knew

What I was feeling.)

Borges also experimented with another

waka

-descended Japanese form, the

TANKA

(also known as

yamato uta

). I shall refrain from entering into the nuances of the form, which appear to be complex and unsettled–certainly as far as their use in English goes. The general view appears to be that they are five-line poems with a syllable count of 5,7,5,7,7. In Spanish, in the hands of Borges, they look like this:

La ajena copa,

La espada que fue espada

En otra mano,

La luna de la calle,

Dime, ¿acaso no bastan?

(Another’s cup,

The sword which was a sword

In another’s hand,

The moon in the street,

Say to me, ‘Perhaps they are not enough.’)

The form has recently grown in popularity, thanks in large part to the publication

American Tanka

and a proliferation of tanka sites on the Internet.

G

HAZAL

The lines in

GHAZAL

always need to

run,

IN PAIRS

.

They come, like mother-daughter, father-

son,

IN PAIRS

I’ll change the subject, as this ancient form requires

It offers hours of simple, harmless

fun,

IN PAIRS

.

Apparently a Persian form, from far-off days

It needs composing just as I have

done,

IN PAIRS

And when I think the poem’s finished and complete

I S

TEPHEN

F

RY

, pronounce my work is

un-

IMPAIRED

.

My version is rather a bastardly abortion I fear, but the key principles are mostly adhered to. The lines of a

GHAZAL

(pronounced a bit like

guzzle

, but the ‘g’ should hiccup slightly, Arab-stylie) come in metrical couplets. The rhymes are unusual in that the

last phrase

of the opening two lines (and second lines of each subsequent couplet) is a refrain (

rhadif

), it is the word

before

the refrain that is rhymed, in the manner shown above. I have cheated with the last rhyme-refrain pairing as you can see. Each couplet should be a discrete (but not necessarily discreet) entity unto itself, no enjambment being permitted or overall theme being necessary. It is usual, but not obligatory, for the poet to ‘sign his name’ in the last line as I have done.

The growth in the form’s popularity in English is largely due to its rediscovery by a generation of Pakistani and Indian poets keen to reclaim an ancient form with which they feel a natural kinship. As with the haiku, it may seem to some impertinent and inappropriate to try to wrench the form out of its natural context: like taking a Lancashire hotpot out of a tandoori oven and serving it as Asian food. I see nothing intrinsically wrong with such attempts at cultural cross-breeding, but I am no authority.

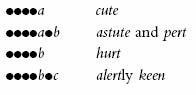

L

UC

B

AT

L

UC

B

AT

is rather

cute

It keeps the mind ast

ute

and

pert

It doesn’t really

hurt

To keep the mind al

ert

ly

keen

You’ll know just what I

mean

When you have gone and

been

and

done

Your own completed

one

It’s really rather

fun

to

do

Full of subtlety

too

,

I hope that yours earn

you

re

pute

.

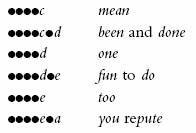

This is a Vietnamese form much easier to do than to describe. L

UC

B

AT

is based on a syllable count that alternates 6, 8, 6, 8, 6, 8 and so on until the poet comes to his final pair of 6, 8 lines (the overall length is not fixed). The sixth syllables rhyme in couplets like my

cute/astute

but the eight-syllable lines have a second rhyme (

pert

in my example), which rhymes with the sixth syllable of the next line,

hurt

. When you come to the final eight-syllable line, its eighth syllable rhymes with the first line of the poem (re

pute

back to

cute

). I don’t expect you to understand it from that garbled explanation. Here is a scheme: maybe that will be easier to follow.

Luc bat is the Vietnamese for ‘six eight’. The form is commonly found as a medium for two-line riddles, rhyming as above.

Completely round and

white

After baths they’re

tight

together.

Milk inside, not a

yak

Hairy too, this

snack

is fleshy

Plates and coconuts, in case you hadn’t cracked them.

16

Proper poems in Vietnamese use a stress system divided into the two pleasingly named elements

bang

and

trac

, which I cannot begin to explain, since I cannot begin to understand them. Once more the Internet seems to have been responsible for raising this form, obscure outside its country of origin, to something like cult status. It has variations. S

ONG

T

HAT

L

UC

B

AT

(which literally means

two sevens, six-eight

, although it begs in English to have the word ‘sang’ after it, as in ‘The Song That Luc Bat Sang’) consists of a seven-syllable rhyming couplet, followed by sixes and eights that rhyme according to another scheme that I won’t bother you with. I am sure you can search Vietnamese literature (or

van chuong bac hoc

) resources if you wish to know more.