The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm (72 page)

Read The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm Online

Authors: Andrea Dezs Wilhelm Grimm Jacob Grimm Jack Zipes

69

A TALE WITH A RIDDLE

Three women were turned into flowers that stood in a field. However, one of them was permitted to spend the night in her own home. Once, as dawn drew near and she had to return to her companions in the field to become a flower again, she said to her husband, “If you come and pick me this morning, I'll be set free, and I'll be able to stay with you forever.”

And this is exactly what happened.

Now the question is how her husband was able to recognize her, for the three flowers were all the same without any distinguishing mark. Answer: Since she had spent the night in her house and not in the field, the dew had not fallen on her as it had on the other two. This is how her husband was able to recognize her.

70

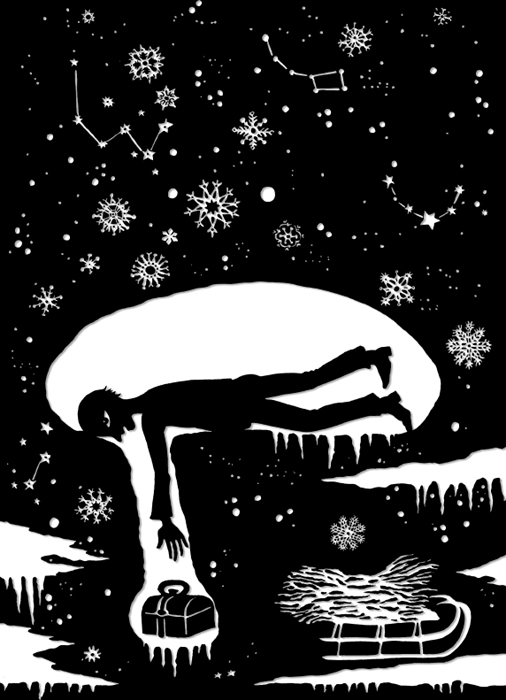

THE GOLDEN KEY

During winter, when the snow was once very deep, a poor boy had to go outside and gather wood on a sled. After he had finally collected enough wood and had piled it on his sled, he decided not to go home right away because he was freezing so much. Instead, he thought he would make a fire to warm himself up a bit. So he began scraping the snow away, and as he cleared the ground, he discovered a golden key. “Where there's a key,” he thought, “there must also be a lock.” So he dug farther into the ground and found a little iron casket. “If only the key will fit!” he thought, for

there were bound to be wonderful and precious things in the casket. He searched but couldn't find a keyhole. Finally, he found a very tiny one and tried the key, which fit perfectly. So he turned the key around once, and now we must wait until he unlocks the casket completely. That's when we'll see what's lying inside.

LIST OF CONTRIBUTORS AND INFORMANTS

Wherever possible the dates and professions of the contributors have been indicated.

Achim von Arnim (1781â1831), important romantic novelist and short-story writer and close friend of the Grimms, who provided a contact to the Berlin publisher of the first edition of

Kinder- und Hausmärchen

.

Clemens Brentano (1778â1842), romantic poet and writer of fairy tales, who encouraged the Grimms to collect numerous folk tales published in the first edition. The Grimms sent him a manuscript of approximately fifty-four tales in 1810 that they used and edited in the first edition of 1812/15. Brentano left the manuscript in the Ãlenberg Monastery in Alsace, and it was first discovered in 1920.

Maria Anna (“Jenny”) von Droste-Hülshoff (1795â1859), member of the Bökendorfer Circle. She and her younger sister, Annette von Droste-Hülshoff, one of the finest poets of the nineteenth century, were close friends of the von Haxthausen family. They were very familiar with all kinds of folk tales, and Jenny, who was very attached to Wilhelm, sent him numerous tales.

Johanna Christiane Fulda (1785â?), one of the sisters in the Wild family, who contributed a couple of tales to the collection.

Georg August Friedrich Goldmann (1785â1855), a personal friend and minister in Hannover, who sent the Grimms several different versions of tales from Hannover.

Anne Grant, author of

Essays on the Superstitions of the Highlanders of Scotland

(1811).

Albert Ludwig Grimm (1786â1872), writer of fairy tales, teacher, and author of

Kindermährchen

(1808). No relation to the Brothers Grimm.

Ferdinand Grimm (1788â1845), the fourth of the five Grimm brothers, who often assisted the Grimms in their research and contributed one tale to the first edition.

He was considered the black sheep of the family, held various positions, and published some books of popular literature.

Georg Philipp Harsdörffer (1607â58), Baroque writer and poet, who published

Der grosse Schau-Platz jämmerlicher Mord-Geschichten

in 1649.

Hassenpflug family, a magistrate's family in Kassel with a Huguenot background, very close friends of the Grimms. Dorothea Grimm married Ludwig Hassenpflug, and the Hassenpflugs as a group provided numerous tales for the Grimms, many of which stemmed from the French literary and oral tradition.

Marie Hassenpflug (1788â1856).

Jeanette Hassenpflug (1791â1860).

Amalie Hassenpflug (1800â1871).

Von Haxthausen family, whose estate in Westphalia became the meeting place for the Bökendorfer Circle. Contact was first made with the von Haxthausen family when Jacob made the acquaintance of Werner von Haxthausen in 1808. A warm friendship developed between the Brothers Grimm and most of the Haxthausens in the ensuing years. Most of the members of the family had a vast knowledge of folk literature. Ludowine and Anna von Haxthausen sent many dialect tales to the Grimms that were never published in any of the editions. These tales were found in the posthumous papers of the Grimms. The von Haxthausen sisters were intent on fulfilling the Grimms' principle of fidelity to the spoken word.

Marianne von Haxthausen (1755â1829).

August von Haxthausen (1792â1866).

Ludowine von Haxthausen (1795â1872).

Anna von Haxthausen (1800â1877).

Ludovica Jordis-Brentano (1787â1854), a sister of the German romantic writer Clemens Brentano. She lived in Frankfurt am Main and provided the Grimms with two tales.

Johann Heinrich Jung-Stilling (1740â1817), whose significant autobiography

Heinrich Stillingsjugend

(1777) and

Heinrich Stillings Junglingsjahre

(1778) contained tales that the Grimms used in their collection.

Friedrich Kind (1768â1843), German poet and librettist, who wrote the libretto for Carl Maria Weber's opera,

Der Freischütz

.

Fräulein de Kinsky, a young woman from Holland, who contributed one tale to the first edition.

Heinrich von Kleist (1777â1811), writer, poet, dramatist, and journalist, who published a version of “Wie Kinder Schlachtens mit einander gespielt haben,” in the

Abendblatt

(October 13, 1810).

Johann Friedrich Krause (1747â1828), a retired soldier who lived near Kassel and exchanged his tales with the Grimms for leggings.

Friederike Mannel (1783â1833), daughter of a minister in Allendorf, who sent several fine tales through letters to Wilhelm Grimm.

Martin Montanus (1537â66), writer and dramatist, who published

Wegkürzer

, a collection of comic anecdotes in 1557.

Johann Karl Augustus Musäus (1735â87), writer and author of one of the first significant collections containing adapted legends and folk tales,

Volksmährchen der Deutschen

(1782â87).

Johannes Pauli (1455âca. 1530), a Franciscan writer and author of

Schimpf und Ernst

(1522).

Johannes Praetorius (1630â80), author of

Wünschelruthe

(1667) and

Der abentheurliche Glückstopf

(1669).

Charlotte R. Ramus (1793â1858) and Julia K. Ramus (1792â1862), daughters of Charles François Ramus, head of the French reform evangelical church in Kassel and friends of the Grimms in Kassel. They belonged to the circle of friends that provided the Grimms with numerous tales; they also put the Grimms in contact with Dorothea Viehmann.

Philipp Otto Runge (1777â1810), famous romantic painter, who lived in Hamburg. He provided two dialect tales.

Friedrich Schulz (1762â98), author of

Kleine Romane

(1788â90). A popular writer whose full name was Joachim Christoph Friedich Schulz, and his story, “Rapunzel,” was published in volume 5 of

Kleine Romane

in 1790.

Hans Sachs (1494â1576), leader of the Nürnberg Meistersinger and prolific author of folk dramas, tales, and anecdotes.

Johann Balthasar Schupp (1610â61), satirical writer and author of

Fabul-HanÃ

(1660).

Ferdinand Siebert (1791â1847), teacher and pastor in the nearby city of Treysa. He studied with the Grimms at the University of Marburg and later contributed several tales to the Grimms' collection.

Andreas Strobl (1641â1706), author of

Ovum paschale oder neugefärbte Oster-Ayr

(1700).

Dorothea Viehmann (1755â1815), wife of a village tailor in Zwehren near Kassel. The Grimms considered her to be the exemplary “peasant” storyteller.

Anton Viethen and Johann Albert Fabricius (1668â1736), authors of

Beschreibung und Geschichte des Landes Dithmarschen

(1733).

Paul Wigand (1786â1866), close friend of the Brothers Grimm, who studied with them in Kassel. Aside from “The Three Spinners,” Wigand contributed nineteen legends to the Grimms'

Deutsche Sagen

(1816â18).

Wild family, a pharmacist's family in Kassel, who were all very close to the Grimm family. Wilhelm eventually married Henriette Dorothea (Dortchen) Wild, who supplied the brothers with numerous tales.

Dorothea Catharina Wild, mother (1752â1813).

Lisette Wild (1782â1858).

Johanna Christiane (Fulda) Wild (1785â?).

Margarete Marianne (Gretchen) Wild (1787â1819).

Marie Elisabeth (Mie, or Mimi) Wild (1794â1867).

Henriette Dorothea (Dortchen) Wild (1795â1867).

Martin Zeiler (1589â1661), Baroque writer, who published a version of “Wie Kinder Schlachtens mit einander gespielt haben” in

Miscellen

(1661).

NOTES TO VOLUMES I AND II

Since there is a fair amount of extraneous material in the Grimms' scholarly notes, I have summarized what I consider to be the most substantial information and translated the variants to the tales. In addition, I have provided the names of the sources for each tale wherever possible. For readers interested in learning more about the Grimms' informants and sources, I recommend the following books.

Rölleke, Heinz.

“Wo das Wünschen noch geholfen hat.” Gesammelte Aufsätze zu den “Kinder- und Hausmärchen” der Brüder Grimm.

Bonn: Bouvier, 1985.

âââ.

Die Märchen der Brüder Grimm: Quellen und Studien

. Trier: Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier, 2000.

âââ, ed.

Es war einmal . . . Die wahren Märchen der Brüder Grimm und wer sie ihnen erzählte

. Illustr. Albert Schindehütte. Frankfurt am Main: Eichorn, 2011.

Uther, Hans-Jörg.

Handbuch zu den “Kinder- und Hausmärchen der Brüder Grimm: EntstehungâWirkungâInterpretation

. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2008.

âââ. “Die Brüder Grimm als Sammler von Märchen und Sagen.” In

Die GrimmsâKultur und Politik

. Ed. Bernd Heidenreich and Ewald Grothe. 2nd rev. ed. Frankfurt am Main: Societäts-Verlag, 2008. 81â137.

Volume I

1.   The Frog King, or Iron Henry (Der Froschkönig oder der eiserne Heinrich). Source: Wild family.

There is a handwritten moralistic version that predates the 1812 story and can be found in the Ãlenberg Manuscript of 1810. It was changed and edited by Wilhelm Grimm for the first edition of 1812. The Grimms considered this tale to be one of the oldest and most beautiful in German-speaking regions, and it was often given the title

“Iron Henry,” named after the faithful servant. The Grimms refer to various versions from the Middle Ages and Renaissance in which a loyal servant binds his heart with iron straps so that it will not break when he learns his master has been cast under a spell. More important for the Grimms, however, was a Scottish version by John Bellenden in the book

Complayant of Scotland

(1548), published in 1801 by John Leyden. The Grimms included Leyden's comment to “The Well at the World's End” in their note because Leyden claimed to have heard fragments in various songs and folk tales. It reads as follows:

According to the popular tale a lady is sent by her stepmother to draw water from the well of the worlds end. She arrives at the well, after encountering many dangers; but soon perceives that her adventures have not reached a conclusion. A frog emerges from the well, and before it suffers her to draw water, obliges her to betroth herself to the monster, under the penalty of being torn to pieces. The lady returns safe; but at midnight the frog-lover appears at the door, and demands entrance, according to promise to the great consternation of the lady and her nurse.

“open the door, my hinny, my hart,

open the door, mine ain wee thing;

and mind the words that you and I spak

down in the meadow, at the well-spring!”

the frog is admitted, and addresses her:

“take me up on your knee, my dearie,

take me up on your knee, my dearie,

and mind the words that you and I spak

at the cauld well sae weary.”

the frog is finally disenchanted and appears as a prince in his original form.

In general, the Grimms were already very familiar with the Scottish and Celtic oral tradition of folk tales in 1812 and continued to give examples of these tales in their notes up through 1857.

2.   The Companionship of the Cat and Mouse (Katz und Maus in Gesellschaft). Source: Margarete Marianne Wild.

The Grimms cite another tale in their notes about the Little Rooster and the Little Hen, who find a jewel in a dung heap. They sell it to a jeweler, who gives them a pot of fat in exchange, and the pot is placed in a cupboard. Gradually, the Little Hen eats the fat until the pot has been emptied. When the Little Rooster discovers this, he becomes so furious that he pecks the Little Hen to death. Afterward, the Little Rooster regrets killing the Little Hen, and so he buries her in a mound of dirt. But his grief is so unbearable that he eventually dies from it.