The Other Side of Midnight (13 page)

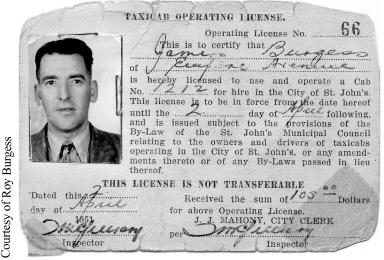

The city was playing catch-up to a swiftly urbanizing society when it passed the“Taxi Bylaw,” in November 1950, adapting existing regulations to meet technological advancements and an increased demand for service. The bylaw made annual taxi driver licences manditory and set minimum employment standards for drivers.

During WWII, with the influx of thousand of Allied troops, taxi stands began to pop up seemingly overnight. Some, like Snow's Taxi on Pearce Avenue and Star Taxi, were operated from dispatch offices in backyard sheds.

In 1946, Frank O'Keefe opened O.K. Taxi on George Street. Many men who had experience taxiing prior to the war returned to the one job where they knew they could make a dollar: taxiing.

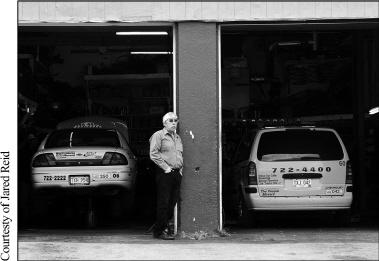

Many taxicab operators had what was referred to in the 1950 “Taxi Bylaw” as a “taxi man's shelter,” a place where they could “escape the elements.”

Pressured by high insurance premiums and other exorbitant start-up costs, few taxicab drivers buy new cars and many are stretched beyond 300,000 kilometres. Regular maintenance is sometimes curtailed because of slim profit margins.

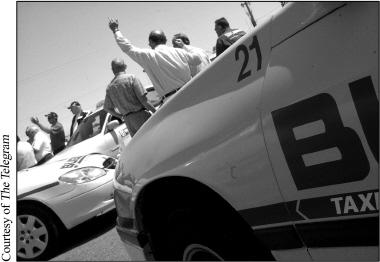

In the highly competitive taxi industry, taxicab drivers rarely show unity. But disunity isn't an insurmountable obstacle. In the summer of 2005, fifty taxicab drivers parked their cars to protest what the drivers thought was an “unfair” increase in stand rent.

During the George Street Festival, a six-day event in late July, an estimated 120,000 people pass through the gates. By three o'clock in the morning, the bars have emptied and the patrons spill out in search of taxicabs.

“No driver shall knowingly drive persons known to him to be engaged

in an unlawful act.”

â St. John's Municipal Act, 1921

“I don't feel safe downtown. Time was, people would stand on

the wharves and come up and say, âHow are you, boy?' and be after

inviting you home and all this. Proper thing! But my dear: it's some

different these past ten or twelve years. I'd not go near the place now!

All those bars, and no shops, and all these people wandering round

on drugs, or something. And no one saying hello. I'm scared to go

there now.”

â Bridie O'Brien, at the Brady House Detoxification Centre,

as recounted in Neigel Rapport,

Talking Violence: An

Anthropological Interpretation of Conversation in the City

“Well, it's like the name says,

down

town.”

â Anonymous Royal Newfoundland Constabulary officer,

from Peter McGahan,

Police Images of a City

For some taxicab drivers, offshore oil has become the symbol of all that is wrong in our urban culture: the drugs, the violent crime and the prostitution. Black gold is ruining Newfoundland's traditional way of life. In fact, this logic has become so popular that it is largely accepted by the public and reinforced by the media, the police and social action groups. The line of reasoning goes something like this: crime follows money. Even as early as 1984, in a report prepared by the RCMP, “Impact of Offshore Oil,” the author predicted that “increased affluence will create problems.”

But is crime really on the rise? Because taxicab drivers who work the night shift reiterate seemingly endless stories of drug addicts and prostitutes, one might begin to think that, in fact, a drug-fuelled crime wave was sweeping through St. John's and quickly spreading out beyond the overpass. It's essential not to take these taxicab stories out of context. Taxicab drivers are regularly exposed to a side of life most people don't know exists and will probably never see. In fact, taxicab drivers are often active links and ready guides between their clients and the underground economy, earning extra cash by connecting customers with prostitutes, drugs and bootleg liquor. They first gained access to these outside earnings when nightclubs, hotels and massage parlours began to spring up in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Statistics Canada has reported that barely 1 per cent of Canadians have used hard drugs like cocaine. In fact, the number has dropped since 2004 from 1.9 per cent to 1.2 per cent. But, in an article entitled “Fighting a Growing Problem,”

The Telegram

said, “Drug use in St. John's has gotten so widespread that buying them on the street is almost as easy as buying a cup of coffee.” Then-RNC Chief Joe Brown went on to state, “Every neighbourhood has someone selling drugs.”

Anecdotal evidence, like the stories from taxicab drivers included in this section, appears to confirm that cocaine use, for instance, has become widespread. Because Social Services pays taxicab companies to shuttle their clients to and from methadone treatments, some taxicab drivers see a proverbial conveyor belt of misery pass through their backseat. According to one taxicab driver, “This is big business for the company.” Substance abuse is nothing new, though, and rates have only increased marginally since 1997.

Statistics can be easily misread and manipulated, and social scientists have long since questioned their use as indicators of crime rates. Consider that crime reporting has increased and so has police enforcement. Since the announcement of the Hibernia discovery in 1979, the RNC, which once did the vast majority of its patrolling on foot, has grown exponentially and has become far more professional. Its area of operation has also greatly expanded. Since 1981, it has patrolled Mount Pearl and now operates in both Corner Brook and Labrador West. Thirty years ago, the Morals and Drug Sectionâa now extinct department of the RNC which also investigated prostitutionâconsisted of only five officers. The number of officers focused on such crimes is now much larger.

Drugs didn't just wash up on our shores when the offshore oil came online, and neither did prostitution. Street prostitutes worked from the harbour and the east end of Water Street servicing foreign fishing vessels long before the advent of oil. Male prostitutes once walked the strip between Hill O' Chips and the Lower Battery in the west end of downtown. The East End Club and the Esquire were known to be regularly frequented by prostitutes. Nor was prostitution the only illicit activity police once had to contend with. Bootlegging was once rampant. In Peter McGahan's study of the Royal Newfoundland Constabulary, one former constable stated, “We had anywhere from ten to twelve bootleggers in the Princess Street area alone.”