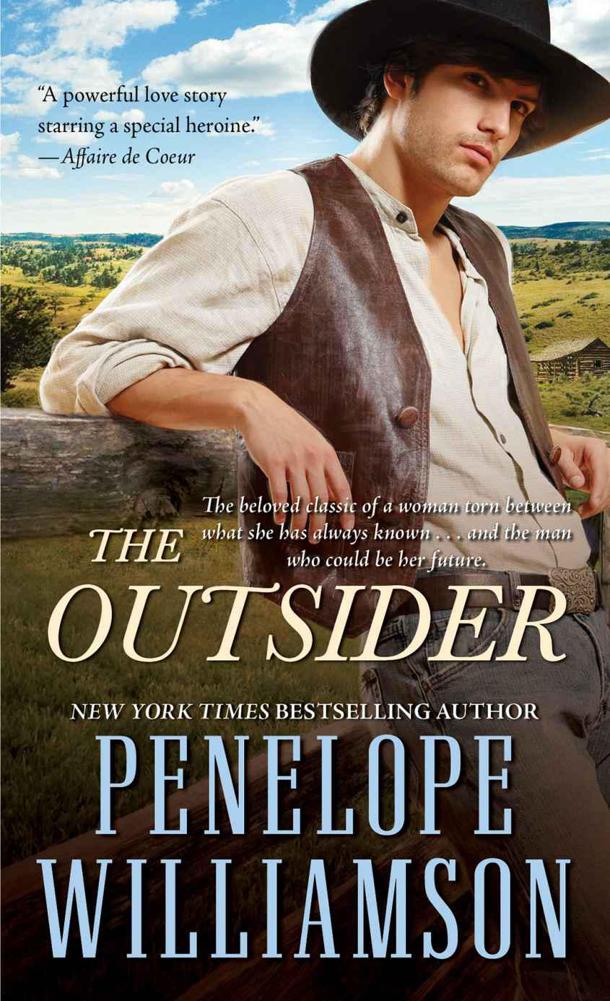

The Outsider

Authors: Penelope Williamson

Thank you for downloading this Pocket Books eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Pocket Books and Simon & Schuster.

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

For Derek.

Because, still, after twenty-five years . . .

H

E CAME INTO THEIR

lives during the last ragged days of a Montana winter.

It was the time of year when the country got to looking bleak and tired from the cold. The snow lay in yellowed clumps like old candle wax, the cottonwoods cracked and popped in the raw air, and spring was still more a memory than a promise.

That Sunday morning, the day he came, Rachel Yoder hadn’t wanted to get out of bed. She lay beneath the heavy quilt, her gaze on the window that framed a gray sky. She listened to the creak of the wind-battered walls and felt bruised with a weariness that had settled and gone bone deep.

She lay there and listened to Benjo stoking up the fire in the kitchen: the clatter of a stove lid, the rattle of kindling in the woodbox, the scrape of the ash shovel. Then the house fell quiet and she knew he was staring at her closed door, wondering why she wasn’t up yet, fretting about it.

She swung her legs onto the floor, shuddering at the cold blast of air that billowed up under her nightrail from the bare pine boards. She dressed without bothering to light the lamp. As she did every morning, she put on a plain dark brown bodice and skirts and a plain black apron. Over her shoulders she draped a black triangular shawl, whose two

long ends crossed over her breasts and pinned around her waist. Her fingers were clumsy with the cold, and she had a hard time pushing the thick blanket pins through the stiff wool. Yet it was the Plain and narrow way to use no hooks and eyes or buttons. The women of the Plain People had always fastened their clothes with pins and they always would.

She did her hair last. It was thick and long, curling down to her hips, and it had the color of polished mahogany. Or so the only man who’d ever seen it let down had once told her. A soft smile touched her lips at the memory. Polished mahogany, he had said. And this from the mouth of a man who’d been born into the Plain life and known no other, and surely never looked upon mahogany, polished or dull, in all of his days.

Oh, Ben.

He’d always loved her hair and so she had to be careful not to let it be her vanity. Pulling it back, she twisted it into a knot, then covered it completely with her

Kapp,

a starched white cambric prayer cap. She had to feel with her fingers for the cap’s stiff middle pleat to be sure it was centered on her head. They’d never had any mirrors, not in this house or the house she’d grown up in.

The warmth of the kitchen beckoned, yet she paused in the cold and murky light of the dawn to stare out the curtainless window. A stand of jack pines along the hill in back of the river had died during the winter and was now the color of old rust. Clouds draped over the shoulders of the buttes, leaden with the threat of more snow. “Come on, spring,” she whispered. “Please hurry.”

She lowered her head, laying it against the cold glass pane. Here she was wishing for spring, but with spring came the lambing time and more than a month’s worth of worry and toil.

And this spring she’d have to live it on her own.

“Oh, Ben,” she said again, this time aloud.

She pressed her lips together against her weakness. Her husband knew a better life now, the eternal life, warm and safe in God’s bosom and the glory of heaven. It was selfish of her to miss him. If only for the sake of their son, she had to find the courage to surrender to God’s will.

She pushed away from the window and made herself smile as she pulled open her bedroom door and stepped into the warmth and yellow light of the kitchen.

Benjo stood at the table, pouring coffee beans into the mill. At the click of the latch his hand jerked, and beans scattered across the brown oilcloth. His eyes, too bright, fastened hard on her face.

“Mem? Why are you up suh—suh—so late? Are you fuh—fuh—fuh . . .” He clenched his teeth together as his throat worked to expel the word that was stuck somewhere between his head and his tongue.

Doc Henry said that if her boy was ever going to get over his stuttering, she had to quit finishing his sentences for him and let him do his own battling with the words. But she did ache to watch him struggle like this, so much that sometimes she couldn’t bear it.

She shook her head as she came up to him, saying, “I’m only feeling a little lazy is all.” Gently she brushed the hair out of his eyes. She hardly had to reach down to do so anymore, he was getting that big. He would be ten years old come summer. Before long he would be growing past her.

The days, how they could flow one into the other without your noticing. Somehow winter, no matter what, turned into spring, and the lambs came and the hay was cut and the wool was sheared and the ewes were mated and then the lambs came again. You got up in the morning and

put on the clothes of your grandmother, you went to the preaching and sang the hymns your grandfather once sang, and your faith was their faith and would be the faith of your children’s children. It was this—the way the days flowed like a river into the ocean of years—that she’d always loved about the Plain life. Time’s passing became a comfort. The sweet sameness of it, the slow and steady sureness of time passing.

“I expect we got ourselves a bunch of hungry woollies out there,” she said, her throat tight with a wistful sadness. “Why, folk can likely hear their bleating clear over in the next country. You’d best get started with hitching up the hay sled, while I see to our own empty bellies. We’re going to be late for the preaching as ’tis.” She ruffled his hair again. “And I’m feeling fine, our Benjo. Truly, I am.”

Her heart ached in a sweet way this time as she watched the relief ease his face. His step was light as he went to the door, snatching up his gum boots from in front of the stove and his coat and hat from off the wall spike. His father had been a big, strapping man with black eyes and hair and a thick, chest-slapping beard. Benjo took after her: small-boned and slender even for his years, gray eyes. Mahogany hair.

He had left the door open behind him, and winter came into the kitchen on a gust of stale wind. “Mem?” he called out from the porch stoop, where he’d sat down to pull on his boots. He craned his head around to look at her, his eyes happy. “Why is it shuh—shuh—sheep’re always eating?”

This time she had no trouble smiling. Benjo and his impossible questions. “I couldn’t say for sure, but I suppose it takes a powerful lot of grass and hay to make all that wool.”

“And all that shuh—sheep p-poop.” He hooted a laugh as he jumped up, stomping his heels down into the boots.

He pumped his arms and leaped off the step into the yard, splattering icy mud all over her porch.

His shrill whistle cut through the air. MacDuff, their brown and white herding collie, burst out of the willow brakes that lined the creek. The dog made a beeline for Benjo, jumping onto his chest and nearly knocking him down. Rachel shut the door on the sound of the boy’s shrieking laughter and MacDuff’s barking. She smiled as she leaned against the door a moment, her head back and her shoulders flat against the rough-hewn pine.

The burp of the coffeepot sent her flying to the stove. Judas, she’d have to hurry with breakfast if they were going to make it to the preaching without being unforgivably late. They met for worship every other Sunday, all the Plain People who homesteaded this high mountain valley. Short of mortal sickness no one ever missed a preaching.

The hot lard sputtered and popped as she laid a thick slab of cornmeal mush into the fry pan. She cracked the window open a bit to fan out the smoke. The mush sizzled, the wind moaned along the sill, and from out in the pasture she heard the sheepherder’s traditional call: “O-vee! O-vee!”

She glanced out the window. Benjo was having trouble coaxing the band of pregnant ewes out from beneath the shelter of the cottonwoods and into the feeding paddock. The silly animals milled in a stubborn bunch. With their long bony noses and wide eyes staring out of ruffs of gray wool, they looked from this distance like a bevy of spooked owls.