The Oxford History of World Cinema (25 page)

Read The Oxford History of World Cinema Online

Authors: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith

produced Oklahoma! ( 1955) and a number of other topdrawer films. Yet, at the end, old

age finally slowed Schenck, and he died in Hollywood a bitter old man, living at the edge

of an industry he had helped to create.

More than the bribery conviction, this woeful ending to their magisterial careers has

robbed the brothers Schenck of their proper due in histories of film. Both deserve praise

for building Hollywood into the most powerful film business in the world during the

1920s and 1930s.

DOUGLAS GOMERY

SELECT FILMOGRAPHY

As producer

Salome ( 1918); The Navigator ( 1924); Camille ( 1927); The General ( 1927); Eternal

Love ( 1929); Abraham Lincoln ( 1930); DuBarry: Woman of Passion ( 1930)

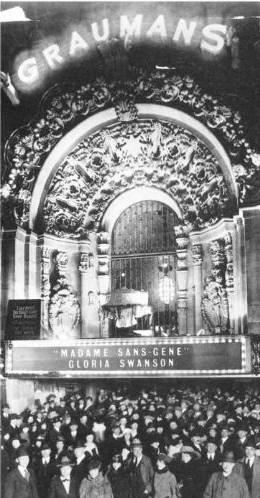

Sid Grauman (1879-1950)

During the 1920s there was no single movie exhibitor in the United States more famous

than Sid Grauman and no theatre more famous than Grauman's Chinese on Hollywood

Boulevard. Sidney Patrick Grauman revelled in his status as movie palace mogul,

flamboyant in every respect, right down to his courtyard of world famous impressions in

cement.According to legend, Norma Talmadge stepped into a block of wet cement while

visiting the Chinese Theatre during its construction, and thus was born the greatest of

theatrical publicity tools. In time Gene Autry brought his horse Champion to imprint four

hooves alongside cement impressions of Al Jolson's knee, John Barrymore's profile, Tom

Mix's ten-gallon hat, and Harold Lloyd's glasses. Grauman should also be remembered for

his innovation of the stage show prologue; live shows, preceding silent films, thematically

linked to the narrative of the feature. During the late 1920s Grauman was justifiably

world famous for these prologues. Before Cecil B. De Mille 's King of Kings ( 1927),

Grauman had a cast of more than 100 play out five separate biblical scenes to fascinate

and delight the audience. Sid Grauman first tasted show business working with his father

in tent shows during the 1898 Yokon Gold Rush. Temporarily rich, David Grauman

moved the family to San Francisco and entered the nascent film industry during the first

decade of the twentieth century. Father and son turned a plain San Francisco store-front

into the ornate and highly profitable Unique Theatre. The 1906 San Francisco earthquake

destroyed the competition and from a fresh start the Graumans soon became powers in the

local film exhibition business.Young Sid moved to Los Angeles to make his own mark on

the world, and a decade later, in February 1918, opened the magnificent Million Dollar

Theatre in downtown Los Angeles. The Million Dollar stood as the first great movie

palace west of Chicago, an effective amalgamation of Spanish colonial design elements

with Byzantine touches to effect an almost futurist design. In 2,400 seats citizens of Los

Angeles could witness the best screen efforts nearby Hollywood companies were

producing. Four years later Grauman followed up this success with his Egyptian Theatre

on Hollywood Boulevard.But the Chinese Theatre was Sid Grauman's crowning personal

statement. At the grand opening on 19 May 1927, D. W. Griffith and Mary Pickford were

present to praise Grauman's achievement. Outside a green bronze pagoda roof towered

some 90 feet above an entrance that mimicked an oriental temple. Inside a central

sunburst pendant chandelier hung 60 feet above 2,000 seats in a flame red auditorium

with accents of jade, gold, and classic antique Chinese art reproductions.Even Grauman's

considerable theatrical skills proved inadequate as the Hollywood film industry acquired

control of the exhibition arm of the movie business. During the Great Depression

Hollywood needed managers who followed orders from central office, not pioneering

entrepreneurs, and the coming of sound made Grauman's prologues passé. By 1930 the

powerful Fox studio, located only a few miles closer to the Pacific Ocean, owned the

Chinese Theatre, and Sid Grauman, showman extraordinary, friend of silent picture stars,

was just another employee.Through the 1930s and 1940s Grauman grew more and more

famous in the eyes of the movie-going public, but his heyday was over. Grauman was like

the stars uptown, under contract, taking orders from the studio moguls, helping promote

the latest studio project. The rise - and fall - of Sid Grauman parallels the history of the

motion picture industry in the United States, from its wild free-for-all beginnings to the

standardized contrl by the Hollywood corporate giants.

DOUGLAS GOMERY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gomery, Douglas ( 1992), Shared Pleasures.

Sid Grauman and Gloria Swanson (in foreground) attending the Hollywood premiere of Léonce Perret's

Madame Sans-

Gêne

at Grauman's Chinese Theatre in 1925

Erich von Stroheim (1885-1957)

The actor and director known as 'Von' to his friends was born Erich Oswald Stroheim on

22 September 1885 in Vienna, to a middle-class Jewish family. In 1909 he emigranted to

the United States, giving his name on arrival as Erich Oswald Hans Carl Maria von

Stroheim. By the time he directed his first film Blind Husbands in 1919 he had converted

to Catholicism and woven various legends about himself, eagerly seized on and

elaborated by the Hollywood publicity machine. In these legends he was always an

aristocrat, generally Austrian, with a distinguished record in the imperial army, but he also

passed himself off as German, and an expert on German student life. His actual military

record in Austria seems to have been undistinguished, and it is not known if he had evern

been to university, let alone in Germany.

The 'German' version seems to have been merely, though bravely, opportunist, helping

him to an acting career as an evil Prussian officer in films made during the anti-German

fever of 1916-18, and contributing to his screen image as 'the man you love to hate'. But

the Austrian identity struck deeper. He became immersed in his own legend, and

increasingly assumed the values of the world he had left behind in Europe, a world of

decadence but also (in both senses of the word) nobility.

Erich von Stroheim (as 'Eric von Steuben') turns his amorous attentions to Francellia Billington ('the wife') in Blind

Husbands ( 1919)

As an actor he had tremendous presence. He was small (5' 5") but looked larger. His gaze

was lastful and his movements were angular and ungainly, with a repressed energy which

could break out into acts of chilling brutality. Both his charm and his villainy had an air of

calculation-unlike, say, Conrad Veidt, in whom both qualities seemed unaffectedly

natural.

His career as a director was marked by excess. Almost all his films came in over-long and

over budget, and had to be salvaged (and in the course of it often ruined) by the studio.

He had fierce battles with Irving Thalberg, first at Universal and then at MGM, which

ended in the studio asserting control over the editing. To get the effects he wanted he put

crew and cast through nightmares, shooting the climactic scenes in Greed on location in

Death Valley in midsummer 1923, in temperatures of over 120° F. Some of this excess

has been justified (first of all by Stroheim himself) in the name of realism, but it is better

seen as an attempt to give a extra layer of conviction to the spectacle, which was also

marked by strongly unrealistic elements. Stroheim's style is above all effective, but the

effect is one of a powerful fantasy, drawing the spectator irresistibly into a fictional world

in which the natural is indistinguishable from the grotesque. The true excess is in the

passions of the characters - overdrawn creations acting out a mysterious and often tragic

destiny.

On the other hand, as Richard Koszarski ( 1983) has emphasized, Stroheim was much

influenced by the naturalism of Zola and his contemporaries and followers. But this too is

expressed less in the representational technique than in the underlying sense of character

and destiny. Str oheim's characters, like Zola's, are what they are through heredity and

circumstance, and the drama merely enacts what their consequent destiny has to be.

Belief in such a theory is, of course, deeply ironic in Stroheim's case, since his own life

was lived in defiance of it. Unlike his characters, he was what he had become, not what

fate had supposedly carved him out to be.What he had become, by 1925 if not earlier, was

the unhappy exile, for ever banished from the turn-of-thecentury Vienna which was his

imaginary home. A contrast between Europe and America is a constant theme in his work,

generally to the disadvantage of the latter. Even those of his films set in America, such as

Greed ( 1924) or Walking down Broadway ( 1933) can be construed as barely veiled

attacks on America's myth of its own innocence. Most of his other films are set in Europe

(an exception is the monumental Queen Kelly, set mostly in Africa). Europe, and

particularly Vienna, is a site of corruption, but also of self-knowledge. Goodness rarely

triumphs in Stroheim's films, and love triumphs only with the greatest difficulty.

Nostalgia in Stroheim is never sweet and he was as savage with Viennese myths of

innocence as with American. His screen adaptation of The Merry Widow ( 1925) turned

Lehar's operetta into a spectacle in which decadence, cruelty, and more than a hint of

sexual perversion could the fantasy Ruritanian air. The Merry Widow was a commercial

success. Most of his other films were not. Stroheim's directing career did not survive the

coming of the synchronized dialogue films, and he had increasing difficulty finding roles

as an actor in the changed Hollywood climate. In his later years he moved uneasily

between Europe and America in search of work and home. In the last, unhappy decades of

his life he created two great acting roles, as the camp commandant Rauffenstein in

Renoir's La Grande Illusion

('The great illusion', 1937), and as Gloria Swanson's butler in

Wilder's Sunset Boulevard ( 1950). It is for his acting that he is now best remembered. Of

the films he directed, some have been lost entirely, while others have survived only in

mangled versions. This tragedy (which was partly of his own making) means that his

greatness as a filmmaker remains the stuff of legend - not unlike the man himself.

GEOFFREY NOWELL-SMITH

SELECT FILMOGRAPHY

As director Blind

Husbands ( 1919); The Devil's Pass Key ( 1920); Foolish Wives ( 1922); Merry-Go-

Round ( 1923); Greed ( 1924); The Merry Widow ( 1925); Wedding March ( 1928);

Queen Kelly ( 1929); Walking down Broadway ( 1933)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Curtiss, Thomas Quinn ( 1971), Von Stroheim.

Finler, Joel ( 1968), Stroheim.

Koszarski, Richard ( 1983), The Man You Loved to Hate; Erich von Stroheim and

Hollywood.