The Parthenon Enigma (58 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

In his forty-four-year reign (241–197

B.C.

), Attalos I accomplished much, but he would be best remembered for two things. First, his

refusal to pay the onerous tribute demanded by marauding

Gauls from the north, a burden on the Pergamene people for years. In fact, within ten years of becoming king, he would soundly defeat the Gallic enemy.

45

Attalos’s second great accomplishment was to raise four sons, two of whom, as Eumenes II and Attalos II, would follow him in peaceful succession, each serving very ably on the Attalid throne. It was under the rule of these three immensely capable individuals across two long generations, spanning 241 to 138

B.C.

, that Pergamon made itself a “New World” Athens, an icon in fact of the old one. Lavishing money on the city’s building program in a measure to rival Perikles himself, they established a vibrant center for science, art, and culture, including a superb library of more than 200,000 scrolls, calculated to attract the most distinguished teachers and philosophers of the day.

IN 200 B.C.

, while harbored on the island of Aegina with his fleet, Attalos I found himself summoned to Athens. He was welcomed at the Dipylon Gate by an ecstatic throng of magistrates, priests and priestesses, and the citizen body as a whole. The people of Athens had a truly astounding honor to offer him: the assembly had voted that Attalos should henceforth be regarded as one of Athens’s founding heroes. A new tribe would be named the Attalis, and his image would be added to the bronze statue group of the

Eponymous Heroes that had stood in the Agora since the 430s

B.C.

46

This was the monument to the city’s ten founding heroes, who had given their names to the Athenian tribes established during the early days of the Kleisthenic democracy, in the last decade of the sixth century.

Thus was an eastern king, with family roots on the Black Sea, made not merely a citizen of Athens but a founding father. That such an honor could be awarded retroactively, as it were, demonstrates the flexibility and practicality of

genealogical

succession myths. It makes the

Parthenon Inscription honoring Nero in

A.D.

61/62 seem rather a small token. But in both cases, the Athenians, having seen better days, were bartering for survival with the most precious thing remaining to them: their singular identity (what we might call the most prestigious “brand” in the ancient world). For assimilating Attalos, they wanted something quite substantial in return: that he join with Rome in defending Athens

against Philip V in the

Second Macedonian War (200–197

B.C.

). Attalos duly complied, bringing soldiers to fight alongside the armies of Rhodes and Rome to defeat the Macedonian foe.

With his new Athenian identity in hand, Attalos I had only to make a few further changes to the Pergamene acropolis to establish an august mythic past for his relatively short-lived kingdom. This he (and his sons) would do via the legend of the hero

Telephos, son of

Herakles.

Meanwhile, before leaving town, the Pergamene king seems to have dedicated on the Athenian Acropolis a series of bronze sculptures celebrating his triumphs over the Gauls in 233 and 228

B.C.

47

Since the fragmentary inscription preserves only the name Attalos, there is a possibility that this offering was made by his son, Attalos II, but the agency of the father is perfectly conceivable. In any case, the installation followed the long-standing tradition discussed in

chapter 6

, by which conquests over eastern enemies were conspicuously commemorated with

shields, swords, and other booty dedicated on, in, or near the Parthenon. Attalos’s victory monuments were set atop the southern ramparts of the Acropolis practically in the shadow of the Parthenon.

Pausanias saw the dedications of Attalos when he visited the Athenian Acropolis in the second century

A.D.

48

He describes a series of bronze statues showing gods battling Giants, Theseus fighting the Amazons, Athenians clashing with Persians, and Pergamene warriors defeating Gauls. Thus, Attalos integrated his own victories over barbarian tribes into the hallowed succession of military boundary events celebrated on the Acropolis from the Archaic period on.

Manolis Korres has even identified the cuttings for the attachment of these statue groups atop the southern wall of the Acropolis.

49

We can envision, then, a series of bronze images set up just beneath the Parthenon and just above the

Theater of Dionysos.

Attalos’s sons, Eumenes II and Attalos II, were quick to understand the value of cultivating this painlessly acquired heritage, and they carried on strengthening ties with Athens and bestowing sumptuous benefactions upon the city. When we look to the

south slope of the Acropolis today, we see the Theater of Dionysos, which, by the Hellenistic period, seated around seventeen thousand spectators (

this page

). But where did these crowds take shelter from the intense sun and occasional rain? Enter Eumenes II, bearing an efficient solution that had already worked at Pergamon. At his home citadel, Eumenes had erected two tremendous

stoas just beneath the theater, one of the colonnades an astonishing 246.5 meters (809 feet) long (

this page

). So the king donated funds for the construction of a smaller version at Athens, just 163 meters (535 feet) long, to the west of the Theater of Dionysos. The “Stoa of Eumenes,” as it came to be called, shows the same system of arcaded buttresses that support the theater at Pergamon, a neat answer for the problem of building up against a steep cliff. Eumenes may have also provided Pergamene engineers to work on the

south slope of the Acropolis.

50

The interior colonnade of the upper story was adorned with palm-leafed capitals, a signature of Pergamene style and of Attalid benefaction.

Eumenes’s younger brother Attalos II (220–138

B.C.

) studied in Athens as a young man, possibly under the philosopher Karneades, head of the Athenian Academy. This would explain the inscription of Attalos’s name on the base of a bronze statue of Karneades found in the Agora.

51

A second dedicator is also named,

Ariarathes, king of Cappadocia, who just happened to be Attalos’s brother-in-law. This joint offering suggests that the two princes might have spent their salad days together in Athens, studying under Karneades. Son of an

Eponymous Hero of Athens, Attalos II was awarded the great honor of Athenian

citizenship in recognition of his benefactions to the city. He famously financed the construction of a great two-storied stoa, its colonnade built entirely of Pentelic marble.

52

Measuring 115 meters (377 feet) long, the so-called stoa of Attalos featured the same telltale Pergamene capitals used in the stoa of Eumenes. In 1952–1956, the

American School of Classical Studies at Athens fully reconstructed the stoa of Attalos on its original foundations, making it one of the only ancient Greek buildings ever to be completely restored and used; to this day it houses the Agora Museum and the Agora Excavations offices and storerooms.

53

The special relationship between Athens and Pergamon is further attested in a series of impressive commemorative monuments on the Acropolis. All four sons of Attalos I competed in the equestrian events at the Great

Panathenaia of 178

B.C.

, each winning his respective competition. The princes continued to contend for prizes in subsequent Panathenaic festivals.

54

To celebrate their victories, they set up two very conspicuous monuments. Eumenes II built a pillar monument, surmounted by a four-horse chariot group cast in bronze,

55

on the terrace just below the northwest wing of the entrance to the Acropolis, in a spot roughly parallel to the placement of the Athena Nike temple at the

south. It should be remembered that the princes’ ancestor

Philetairos had introduced the worship of Athena Polias Nikephoros at Pergamon back in the second quarter of the third century

B.C.

The pairing of the Attalid victory monument with the Athenians’ own temple to Victory emphatically manifested the special link between the two cities. The chariot group would come and go, but the pillar base proved durable: it later held bronze statues of Antony and

Cleopatra, and following their defeat at

Actium in 31

B.C.

it was rededicated to the great hero of the battle, the Roman consul

Marcus Agrippa. The monument can be seen to this day just to the left, in front of the northwest wing of the Propylaia as one enters the Sacred Rock.

A second monument was erected, probably to commemorate Attalos II’s victory in equestrian competitions that he seems to have won at

three separate

Panathenaias: 178/7, 170/69, and 154/3

B.C

.

56

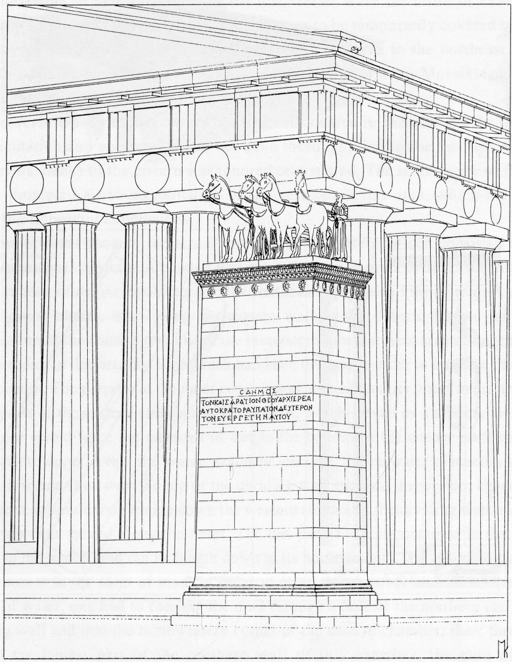

Its towering marble podium supported a bronze four-horse chariot group (facing page).

57

Erected at the northeast corner of the Parthenon, the monument reached the height of the temple’s architrave, bringing it face-to-face with the

shields dedicated by Alexander after his victory at Granikos. It also directly faced the northernmost metope of the Parthenon’s east façade (no. 14), which shows

Helios driving his chariot up from the watery, and fishy, depths (

this page

). One can only wonder how close the Pergamene dedication stood to the famous statue group of

Erechtheus battling Eumolpos, a leading work by the master sculptor Myron in the mid-fifth century

B.C.

Pausanias describes these sculptures as set up “right by the temple of Athena.”

58

Thus, by the Hellenistic period, the Parthenon precinct was filled with victory monuments from across the ages, juxtaposing images of venerable local heroes with those of newly minted Attalid kings.

Reconstruction drawing of victory monument of Attalos II, with bronze quadriga on tall pillar at northeast corner of Parthenon, by M. Korres. (illustration credit

ill.110

)

BACK AT PERGAMON

, the Attalids imported cults that had long existed at Athens.

59

They combined the worship of Athena Polias with that of Athena Nike to produce the cult name Athena Polias Nikephoros. Beneath the Pergamene theater stood a small temple of

Dionysos, mirroring exactly the plan at Athens, where the temple of Dionysos sits just below his theater on the Acropolis’s south slope.

60

High above the theater at Pergamon, we find the sanctuary of Athena Polias, again a direct quotation of the plan at Athens, where the sanctuary of Athena sits atop the theater, crowning the Acropolis citadel (

this page

and

this page

). So important was visual correspondence with the Athenian model that Pergamene builders turned their Athena temple off the standard east-west axis so that it faced north, its long flank appearing above the theater just as the Parthenon does above the

Theater of Dionysos on the Acropolis’s south slope.

The precinct of Athena Polias Nikephoros, established at Pergamon by Philetairos, was enhanced with double-storied stoas added by Eumenes II.

61

The upper balustrades of these stoas were ornamented with sculptured reliefs depicting trophies of Pergamene victories: great panoplies of weapons, shields, armor, standards, and

aphlasta

(apulstres, tall ornaments that decorate the sterns of ships and symbolize maritime power). In this, the Pergamene shrine of Athena Polias Nikephoros

borrows from the temple of Athena Nike at Athens. We will remember the ninety-nine

shields seized by

Kleon from the

Spartans at

Sphakteria and hung as trophies around the podium of the Nike temple. The symmetry between the booty displayed at Athens and the seized weapons depicted on the Pergamene balustrade makes the association of the two sanctuaries all the more emphatic.

The so-called

Altar of Zeus, set high on a terrace near the summit of the Pergamon acropolis, was a monument like no other (below).

62

It measured roughly 35 square meters, or 100 Ionian feet, making it a true

hekatompedon

, or “hundred-footer.” The date of its construction and its identification as an altar are much debated.

63

While it has traditionally been placed during the reign of Eumenes II, new study of context pottery has pushed the date down to the very end of his reign and extending into that of Attalos II and, even possibly, that of Attalos III.

64

Work appears to have begun after 165

B.C.

, or even later, in commemoration of Eumenes II’s victories over the

Gauls in 167–166

B.C.

In any case, the monument was never completed.