The Passport in America: The History of a Document (18 page)

Read The Passport in America: The History of a Document Online

Authors: Craig Robertson

Tags: #Law, #Emigration & Immigration, #Legal History

The initial attempt to verify citizenship claims through specific documents authorized by designated officials occurred in the second half of the nineteenth century, when most individuals still considered personal statements and relationships the primary ways to confirm individual identity.

8

Voting, another forum in which citizenship had to be verified, underscores the limited importance of record keeping and identification documents to interactions between individuals and government. The community surveillance organized on election day occurred in the absence of voter registration and with the assumption that voters could not prove their right to vote with documents.

9

While the verification of race and ethnicity were important to voter eligibility, concerns also existed over the age, residence, and mental competence of potential voters. At the polling booth the party appointed challengers and the “election judge” used three main sources of evidence to resolve these concerns: physical appearance, the collective memory of the community, and the word of the would-be voter. Community practices and norms determined the viability of any evidence, with the result that the decisions made at the polls often had a limited foundation in formal electoral law. Age was frequently decided through collective memory, sometimes by connecting a birth to an extraordinary event, or whether it was known the voter was able to grow a beard. Where a man’s washing was done was commonly considered sufficient evidence of residence and his right to cast his vote in the precinct.

10

In urban areas voting often could not depend on such communal knowledge, but with few if any documents available, the body and personal appearance also played an important role particularly when race and ethnicity became contentious issues at polls. Voter registration laws first appeared in urban centers to counter concerns about residence. However, these laws offered only limited assistance in the verification of voters. Before the regular adoption of typewriters, the lists were handwritten and could not necessarily be read with accuracy. Many voters were unable to spell their names, with the result that election judges and clerks attempted to make phonetic matches. This task was made all the more difficult as early

lists were not alphabetized. Voter registration also did not immediately solve the problem of verifying residence, as most cities lacked systematic criteria to identify individual houses.

11

The attempt to standardize the application process through preprinted forms, official documentary evidence, and designated officials encountered the practices and etiquette of this relatively undocumented world. Even when documents were used in local interactions, there was still the assumption that they could be supported by (or even trumped by) local extratextual evidence, as in the attempt of John S__’s attorney to connect his passport application and naturalization certificate through personal knowledge despite a difference in the spelling of his name. The use of documents was intended to marginalize the predominately face-to-face interaction and the (seemingly) unmediated culture in which they occurred. The dramatic increase in geographical size and population of the United States also challenged the on-going viability of localized forms of verification. In both instances, this lead to more geographical mobility that challenged the social relations that had underwritten identification practices in local communities. This points to the often-recited argument that the documentation of individual identity originated to provide proof of identity in the absence of a communal group as part of the displacement of the modern world. Cultural historian Matt Matsuda describes this as the belief that centrally-issued identification documents developed to replace “the assurance and authority of the ‘small circle’ of familiars who could attest to the good name of an individual… [with] the distant authority of an ‘official’ document, the assurance of an encompassing administration distilled down into a card.”

12

However, in the United States until well into the twentieth century, the assurance of the state could not be

purely

recorded. The small size of the federal government relative to the geographic size of the United States meant the federal government was limited in its administrative reach and frequently struggled to function successfully without relying on local practices and what was perceived as their potential for bias.

13

In 1845 Secretary of State James Buchanan issued the first departmental circular regarding the passport application process, but only in a subsequent circular in 1846 did the department describe the specific documentary evidence required before a passport could be issued.

14

In the absence of critical twentieth-century seed documents such as the birth certificate and driver’s license, the circular introduced

a combination of documents and designated local officials and individuals to provide the basis for claims to citizenship and personal identity. All applicants had to provide an affidavit witnessed by a notary public and signed by another citizen to verify their personal identity and claim to citizenship. To facilitate this, by the 1860s the application form was printed as an affidavit. The top half of the form contained text that stated the applicant was a citizen, and the applicant inserted his name, place of birth, and the country or countries he intended to visit in the appropriate blanks. Below this was a space for the applicant to sign, and then underneath that a space for a notary public to record the date of the application and affix his signature and seal. The lower half of the form was a statement in which a witness declared his personal knowledge of the applicant and the truth of the applicant’s statement. There was a space underneath for the witness’s signature and for the notary public to sign and date this declaration. At the bottom of the form was a space to fill in the physical description of the applicant.

15

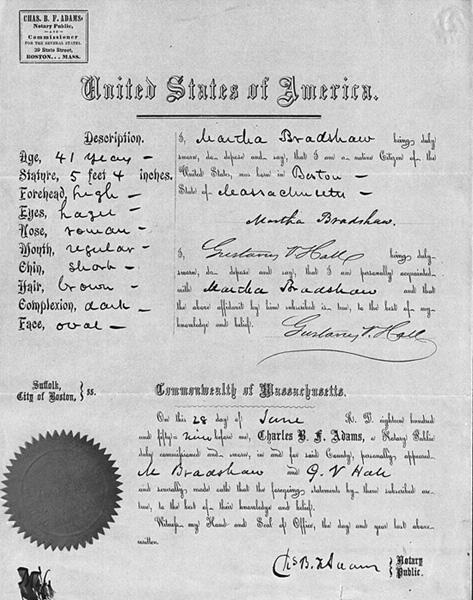

Notaries public frequently had their own version of the application form printed (

figure 6.3

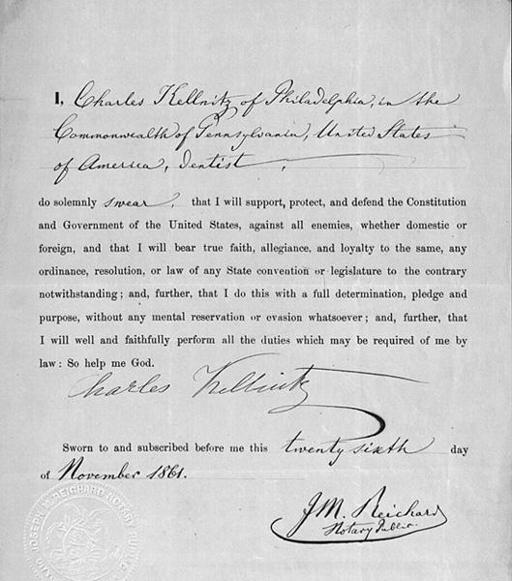

). Naturalized citizens also had to send in their naturalization certificate. From 1861 applicants were required to submit additional proof of citizenship in the form of an oath of allegiance—the start of the Civil War motivated the demand for verification of more than the mere fact of citizenship (

figure 6.4

).

16

In contrast to the affidavits and certificates used to establish citizenship, the department considered an oath to offer evidence that a citizen retained ongoing loyalty to the nation-state. While oaths are a relict of medieval statecraft, in the modern state they tend to appear in response to general climates of fear and particular crises such as war and rebellion.

17

In the United States the need for a citizen to affirm supreme loyalty to the nation and the federal government was significant in establishing the nation-state as a tangible site for loyalty and identity over local ties and affiliations.

18

The oath of allegiance, along with other documents demanded as evidence of citizenship, existed not only within the project of reifying the nation, but also as part of an attempt to establish a centralized administrative state through standardized practices that eliminated local modes of information collection. The attempt to assert control over the production of knowledge was hindered by the ad hoc use of bureaucratic procedures in the second half of the nineteenth century. This derived from the less than rigorous application of procedures and the limited range of the federal government’s administrative structure. In the case of the passport this was further accentuated by the lack of federal interest in the document, particularly outside of the diplomatic and consular service. The acceptance, albeit inconsistently, of

Figure 6.3. Passport application form printed by a notary public, 1859 (National Archives, College Park, MD).

alternative oaths until the end of the nineteenth century was but one example of the way in which secretaries of state and department officials undercut attempts to create a uniform passport application process.

19

A more significant consequence of the partial reach of the state in the passport application was the need to the use affidavits witnessed by notaries

Figure 6.4. Oath of Allegiance from passport applicant, 1861 (National Archives, College Park, MD).

public. With insufficient direct knowledge of specific local interactions, the federal government had to rely on preexisting structures such as notaries public to verify evidence of identity. Though usually a stranger to both the applicant and the State Department, these people were “known” to department officials through the recognition of the official position of the “notary public.” As both an official stranger and official witness, the notary public recorded the applicant’s statements about personal identity and citizenship on behalf of the federal government in the absence of locally deployed

federal officials. Affidavits sworn in front of notaries were an attempt to establish an acceptable degree of reliability in personal identification that adhered to the new standards of bureaucratic objectivity, not trust in self-verification of identity. However, in the absence of birth certificates, the fact of citizenship still originated in someone’s personal claims, not in official record-keeping practices; most states did not pass laws requiring the registration of births until the first decades of the twentieth century. Further, the precise nature and authority that made a notary’s official witnessing useful to the federal government often appeared to be unclear to both applicants and notaries. Applications arrived in the department without the signature or seal of the notary and with the applicant’s place of birth omitted. Aside from sloppiness, these incomplete applications also point to a failure to fully grasp that in the developing articulation of reliability through documents, the successful translation of a personal statement into a legal and administrative fact required that a document contain evidence of the presence and authority of the appropriate official. To simply record an oral statement on a piece of paper did not turn the statement into what was coming to be seen as an official and usable fact. An affidavit could only give legal authority to a claim to citizenship and identity if it recorded the notary’s presence at the swearing of the statement, which was understood to authenticate the document and therefore the statements that appeared on it. It was not to be assumed through implicit association, but rather verified through a seal, signature, and date that located the source of authority in the actions of a designated official. The number of applications received without verification of the notary public’s authority was one reason the department printed forms to be returned with incomplete applications. These forms were in regular use by the 1880s and represent the move toward a more consistent enforcement of application requirements and, therefore, a more assertive attempt to claim control of the issuance of the passport. Beyond an attempt to further standardize the application process, their use indicates that the department received incomplete applications in sufficient numbers to warrant the printing of specific forms—illiteracy in documentation was not unique to notaries public.