The Passport in America: The History of a Document (17 page)

Read The Passport in America: The History of a Document Online

Authors: Craig Robertson

Tags: #Law, #Emigration & Immigration, #Legal History

Official attempts to standardize photographs constituted an effort to ensure that the image on the passport fulfilled the promise of accuracy through which officials understood the utility of photography. While this was done primarily through codifying the precise pose and format of the image, it was also done via other regulations that continued to frustrate some applicants—even more than the cost. This frustration came as people encountered requirements that overrode an expected trust in their character. By the early 1930s State Department practice resulted in the demand that no passport photograph should be more than two years old—any older and it was believed the image could not be guaranteed to offer a sufficiently

accurate likeness.

41

This demand for new photographs was considered an affront. In requiring recent photographs the state’s claim to know someone became read as a claim to know what they looked like over and above their own perception.

42

The comments of a consul assigned to inspect U.S. passports abroad offer another example of the official struggle to determine if a person looked like a passport photograph; in this case the problem different visual practices created at the moment of official recognition. In contrast to what a person may have worn for a passport photograph, he complained, “When the passport is presented to the inspecting officer the holder of it is always dressed for travel with complete headgear and with wraps. It is therefore often impossible for the inspecting officer to determine at a glance whether the person who presented the passport and the person who sat for the photograph are one and the same.”

43

In the technical specifications of the passport photograph, state officials sought to emphasize the “natural” features of a person’s face to highlight uniquenesses and differences. But amid the cultural accoutrements of travel, that individuality was harder to discern. The visual effects of travel fashion, closer to the visual coding of leisure in the conventions of portraiture, affected the utility of the passport photograph to provide an effective comparison at this early moment in its “modern” history. In this particular example the official effort to stabilize identity according to specific requirements, to freeze it in time, failed because the inspection process went by too quickly.

Thus, while a photograph was thought to provide a more objective representation than a written description, the “accuracy” of the photograph had to be read against an individual’s changing appearance. The purported strength of photographic representation was that it produced a stable and fixed object that provided an accurate point of comparison for state officials. This belief in a stable identity provides the fiction at the heart of the modern identification project—the broader version of the “legal fiction” that introduced the photograph into the courtroom. This formal identity (which coexisted with a reality that contradicted it) would be increasingly naturalized as the twentieth century progressed. However, in examples such as the “distortion of passport photography,” this identity was viewed as anything but natural. Similarly, the consul’s complaint about dress shows that the authority attributed to identification photography depended in part on a need to learn to recognize the precise likeness captured in a photograph. As Trachtenberg argues, a “portrait is a picture ‘of’ someone, the ‘of-ness’ consisting

of a likeness, a correspondence of features between what the image conveys and what the living figure looks like.”

44

The ability to see a correspondence between a person and the features highlighted in the photograph was just that, a skill that had to be acquired.

Another way to understand the standardization of the passport photograph is therefore as the production of a useful and easily seen “of-ness.” The regulation of the passport photograph is an attempt to improve the accuracy of the “likeness” in a photograph. Initial difficulties in using the photograph to verify the identity of the person who presented the passport and complaints from people that their passport photograph did not resemble them make explicit that the identity in the passport was an official standardization or bureaucratic expression of personal identity; it was an identity distinct from a person’s understanding of his or her personal identity. A photograph shorn of accoutrements represented the “simplification” at the core of modern identification: the official representation of only that part of a person’s identity relevant to the particular governing practice.

45

The “modern” practices the identification photograph made visible facilitated the production and verification of an identity that the state could use to both verify and remember individuals. The difference between this identity and a more romantic sense of individualism and self-knowledge is offered in a Passport Division anecdote recounted in a newspaper profile of the office. As part of her passport application, an Illinois woman sent two photographs as required along with her passport application to Washington, D.C. But these were purportedly different photographs: “along with the 1928 model she sent one with leg-o-mutton sleeves.”

46

The applicant seemingly sought to give historical depth to her claims to identity; she had always been the person she claimed to be. However, her attempt to establish her identity temporally was in contrast to the new intentions of identification. While she sought to connect the present to the past, modern identification practices were organized to link the present to the future. The standardization of the passport photograph across multiple copies was demanded in anticipation of the need for future verification through comparison with the photograph on the passport—to put a face on the information contained in the file according to the anticipatory archival logic of identification practices. As the following chapter makes clear, the claims to objectivity that determined the visual representation of identity in the passport photograph can be also seen to constitute the verification of citizenship through documents as an administrative fact useful to the changing governing practices of the long nineteenth century.

6

Application

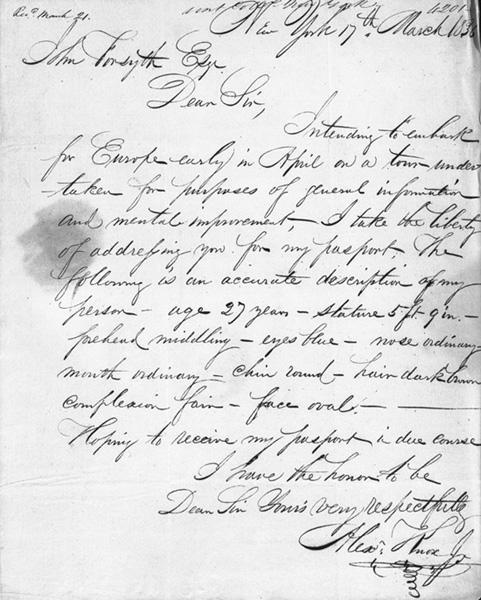

Until the 1840s most passport applications arrived in the State Department in the form of a personal letter addressed to the secretary of state (

figure 6.1

). The letter usually included some description of physical appearance, occasionally a declaration of citizenship, and more frequently a brief outline of the writer’s travel plans. While applications were returned because of insufficient evidence of citizenship, passports were also issued to people not entitled to them.

1

The returned applications were usually from naturalized citizens, as is apparent from the printing of an application form for naturalized citizens, which took the form of an affidavit from a notary, though it seems to have been rarely used after it was introduced in 1830.

2

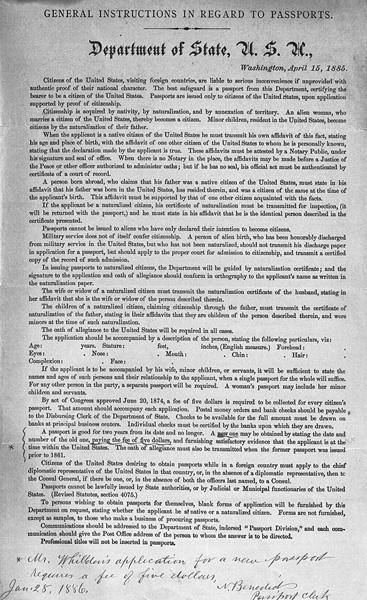

In the mid-1840s the State Department issued formal guidelines for applicants, including a description of the documents that now had to be submitted to prove personal identity and citizenship. However, it seems that only in the last decades of the nineteenth century did officials start to consistently enforce these requirements; in 1896 the State Department changed the name of its guidelines for applicants from “General Instructions in Regard to Passports” to “Rules Governing Applications for Passports,” indicating this new attitude to the passport application (

figure 6.2

).

With the ad hoc enforcement of application requirements, it is perhaps not surprising that at the end of the century an applicant could express “considerable annoyance and exasperation” when officials deemed his word insufficient evidence of citizenship.

3

In 1897 this particular applicant, Donald McKenzie, applied for a passport on behalf of his elderly mother. Although not born in the

Figure 6.1. Application for a passport, 1836 (National Archives, College Park, MD).

United States, she claimed citizenship through the naturalization of her father while she was a minor and her later marriage to a naturalized citizen.

4

Both men had died by the time of her passport application and neither of their naturalization certificates could be found; a courthouse fire was assumed to have destroyed one record, and the other could not be found nor the location of

Figure 6.2. General Instruction in Regard to Passports, 1885 (National Archives, College Park, MD).

the naturalization remembered. In lieu of these documents McKenzie offered the statement that her “two living children are both native born and voters and that fact together with mother’s 47 years of continued residence, should give her citizenship even disregarding ‘naturalization papers.’ “But in the absence of verification through the proper documents, McKenzie’s

statements

were simply that; they were not the “

facts

” the clerk wanted and that McKenzie assumed them to be. The demand for impersonal documentary evidence over personal vouching defied McKenzie’s sense of logic; “The absurdity of your asking for naturalization papers which were taken out probably 45 years ago (in the case of her father) and a quarter of a century ago (or more) in the case of her husband, is too evident to be gainsaid.”

5

The frustration passport applicants like Donald McKenzie felt in response to demands for documents originated in a failure to comprehend that increasingly in official interactions, proof of identity no longer depended on the authenticity of personal claims; identification was not contingent on an individual’s personal reputation or character, or simply his word. In contrast to these expectations, official identity was in the process of becoming a bureaucratic expression, an identity distinct from other ways in which individuals represented themselves publicly. As the number of interactions between individuals and the federal government increased, officials began to rely exclusively on the information contained in documents; they wanted facts that could be understood from afar, without need of any local knowledge as they sought to establish the passport’s credentials as a certificate of citizenship. This required the

intentional

collection of specific documentary evidence within the purview of the state. But the attempt to standardize official identification in this manner developed in an ad hoc manner as the problems associated with the name, physical description, and photograph illustrate. The State Department’s inconsistent but increasingly rigorous adherence to documentary evidence of citizenship contributed greatly to both the aggravation applicants felt when they could not comply and also to their confusion about why state officials could not trust their word as to who they were. The localism that had dominated governing practices in the United States throughout much of the nineteenth century undoubtedly accentuated the perception of this new mode of identification as a relatively impersonal form of governing; somewhat surprisingly the earlier introduction of a fee for passports had apparently not signaled to applicants this more impersonal relationship between state and citizen. In 1862 a passport fee of $3 was introduced, which was subsequently increased to $5 before

being reduced to $1 in 1888; from 1871 to 1874 there was no passport fee.

6

Officials viewed the fee as an important source of revenue, especially as the number of passport applications dramatically increased in the second half of the century, as did the number of clerks required to issue them. Although many applicants considered a passport to be something like a letter of introduction or protection, the fee appears not to have been viewed as an affront, barely even registering as an annoyance.

7