The Pope's Daughter: The Extraordinary Life of Felice Della Rovere (30 page)

Read The Pope's Daughter: The Extraordinary Life of Felice Della Rovere Online

Authors: Caroline P. Murphy

Tags: #Social Sciences, #Women's Studies, #History, #Renaissance, #Catholicism, #16th Century, #Italy

Perhaps because of the length of his service with her, Statio had achieved a comfortable relationship with Felice. This is evident from his style of writing to her, which is unusual between a servant and a member of the nobility. His letters can show something of a flair for the dramatic. On one occasion he wrote to her, ‘I am sending you ten

palmi

of velvet. The merchant told me that it was the best, and that one should not dress in anything else. I have faith in him at the moment, but if it does not satisfy you, I will quarrel with him so terribly that I will almost wring his neck.’

2

When Felice did not immediately send him the money from Vicovaro and Statio needed to pay for the serge for Girolamo’s shirt and Julia’s shoes, he first wrote to her household manager there, Hippolito della Tolfa, asking him to ‘solicit our lady to send me the money’. The household expenses were mounting up, and so when that approach did not appear effective, Statio, in the body of a much longer letter to Felice, informed her, ‘Your ladyship knows that I have been in Rome nine weeks now and I am counting out every expense from the purse. Your ladyship knows what it is to live and spend money in Rome, in such a way that I am now finding myself in a real calamity, and I could never have believed that I would see my ruin. I do not say this to contradict your will in any way. My obligation and debt to you are such that I would spill my own blood for you for your goodness towards me.’

3

Felice clearly allowed Statio to write to her in this way without fear of reprisal. She appears never to have sent him the kind of sharp rebuke that Hippolito della Tolfa, his counterpart at Vicovaro, sometimes received. Statio did much more than just shop for Felice. He served as her linchpin when she was absent from Rome. He sent her all the latest gossip, which ranged from who had come to Monte Giordano to what was going on at the Vatican and the latest international scandals. ‘Let me tell some news,’ Statio reported gleefully to Felice in

1517

, ‘which came in a letter from Venice. The Great Turk [Selim I] has a very beautiful Christian slave with whom he is in love. One morning he gave a fine meal for all the court, and she was present, elegantly dressed with magnificent clothes and jewels. At the end of the meal he asked all if she was most beautiful. They were all stupefied and agreed.’ Statio had a novel solution to the problem of the dangerous and powerful infidel, whose empire was expanding rapidly: ‘All we have to do’, he concluded, ‘is to wait for a man like her who can conquer the kingdom.’

4

When Statio was not speculating on international events, fighting with merchants, or declaring he would shed his own blood for Felice, he distributed licences for the acquisition of another valuable commodity that Felice controlled: wood. Wood was used for the making of furniture, the heating of the home, and even as currency in its own right, bartered for other commodities. The

1518

inventory of the Orsini estate indicated which fiefs had forests attached to them, including Trevignano, Galera and Isola. The woods were mainly of oak trees, for this was the ancient land of the Sabines, which even in

64 bc

, as the Greek writer Strabo described, ‘produces acorns in great quantities’.

5

In other words, for over fifteen hundred years, the land Felice now ruled had always been the land of oaks, the land of the Rovere. Care had to be taken that the woods were not over-felled each year. Not only would they take a long time to restock, opportunities for hunting would also be reduced. So the woods were patrolled by Orsini servants, and anybody who wanted to chop wood had to have permission in the form of a licence stamped with Felice’s seal. A sample blank licence gives an indication of the form this permission would take: ‘Felice della Rovere Orsini allows the bearer to chop wood in the holding of Isola, reserved for the bearer and two pack horses for the duration of one month. We order and command our bailiff and the guards not to harm the bearer because the bearer has paid to chop down trees. Validated in Rome,

1531

.’

6

Not surprisingly, such licences were in great demand. Even Felice’s half-sister, Francesca De Cupis, wrote to her, grateful for having received ‘the licence for wood’. In January of

1521

, perhaps because it was particularly cold, the

ministra

of the Sisters of the Pietà wrote to Felice with the following request:

Our lady benefactor: The faith which we have in you, and our own great necessity gives us the strength to avail you of our needs and to beg you, for the love of God, that you might wish to concede gracefully in allowing us to go to your forest at Galera or Isola for some logs of wood, to be carried away by the one animal we possess. This would be doing us a great charity, for which we would be eternally obliged, if you would deign to send the licence of authorization for your bailiff. As always, we recommend ourselves to you.

7

In addition to these impoverished nuns, there were many high-ranking clergy who sought licences from Felice, among them Cardinal Bernardo da Bibbiena. In the reign of Felice’s father, Bibbiena had been secretary at the Vatican to the Medici cardinals. Felice and he had always had some peripheral contact and she sometimes appeared in his reports back to Florence. But during the reign of Pope Leo X, Bibbiena had become a figure of much greater importance and influence. He had been the boyhood tutor of Giovanni de’ Medici, who was now Leo X. He had become Leo’s most trusted adviser. Leo had made him cardinal deacon, had given him his own former titular church of Santa Maria in Domnica in Rome, and a suite of rooms in the Vatican Palace, because Bibbiena could not afford a palace of his own. Raphael, before his death, was to have married Bibbiena’s niece, who is now buried next to him in the Pantheon. Bibbiena now wanted to acquire wood from Felice, and Felice’s servant Giovanni Battista della Colle reported to her on

16

January

1520

, that, ‘Monsignor Reverend of Santa Maria in Portico recommends himself to you. He begs that you would send him a bull to let him chop wood in the forest at Galera.’

8

Unfortunately, when they went out to Galera, Bibbiena’s men ran into difficulties. The Cardinal wrote personally to Felice, ‘You would give me much grace if you could let me send three of my mules to Isola. I do not know why, but my men fought with those at Galera, and they do not want to go back there again.’

9

According to Statio, whom Bibbiena visited in person, the men of Galera had ‘torn the licence into shreds’.

This was not the only time that problems occurred between curial servants and the woodsmen. The Romans, dressed in the livery of their cardinal employer, fancied themselves a cut above these peasants and undoubtedly put on airs not appreciated by the countrymen, even if they did come with authorization from Felice. Felice herself was absolutely furious at the way in which the head woodsman had treated the servants of Alessandro da Nerone, who was the

maestro di casa

of the Pope himself. They had refused to let Nerone’s men take away the wood they had chopped down. When she heard what had occurred, Felice wrote to Statio to tell him to let the head woodsman know exactly what he had to do: ‘Tell him to send out again all the wood they took from the mule-drivers of His Holiness, under the command of Alessandro Neroni, His Holiness’s

maestro di casa

, at the expense of the head woodsman, and with this, show him how he has displeased me with his insolence.’ To confirm that the curia would continue to be allowed to take wood, she added, ‘And now send a licence to Pietro Oromabelli [a papal secretary], so that he can send mules for the wood from my forest.’

10

For Felice, providing papal servants with goods they needed was a means of ensuring her continued position and influence at the Vatican. Support from the papacy was her best protection against any attempts by the Orsini to challenge her leadership. She also came increasingly to rely heavily on her half-brother, Cardinal Gian Domenico, who had grown from an ‘ignorant young boy’ into his sister’s most loyal and trusted servant.

chapter 14

Felice della Rovere had risen far above the ranks of the bureaucrat’s family in which she had spent her earliest years, but she never left them behind. The de Cupis had provided her with stability and affection when those elements were lacking in her life. Such a bond was unusual. Few illegitimate daughters of the elite were allowed to bond with their mothers. They were frequently removed at an early age from this maternal orbit, brought up with their father’s family, or placed in a convent. Yet Felice had always returned to her mother’s home. Despite the fact that Felice was now Rome’s most powerful woman, her mother Lucrezia still fretted over her as if she was still a young girl. Learning that her thirty-four-year-old daughter was afflicted with toothache, she wrote to her, ‘I learned that you have a pain in your teeth, which upset me. I beg that you warm up a bit of vinegar in a well-heated pitcher, and a pinch of salt, and three or four laurel leaves, and hold it as long as you can in your mouth, and then it will not hurt.’

1

Despite her motherly concern, Lucrezia understood the protocol of writing to the daughter who was now the Orsini Signora. She addressed her as ‘most illustrious lady’ and signed herself, ‘your most obedient Lucrezia’. Securing a cardinalship for Gian Domenico was the best way Felice could raise her maternal family’s status to one commensurate with her own.

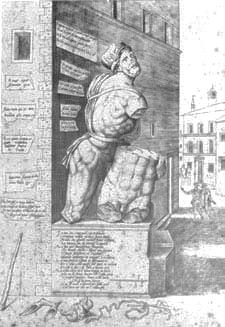

Gian Domenico understood very well how and why he had become a cardinal, and where his loyalties and duties lay. He appears in very few ecclesiastical records for almost a decade after his appointment as cardinal and was not an active member of the curia. The reason for his low clerical profile is that his regular position was as his sister’s

aide de camp

, a fact widely recognized in Rome. In satirical verses pinned to the Pasquino statue, Giuliano Leno had been mocked for his greed but Rome’s cardinals were easy targets as well. Gian Domenico was derided for being ‘dear to his mother’ or for ‘the love he bears his relatives’, references to Lucrezia, with whom he lived, and Felice, who had made him a cardinal.

2

The individuals in question had little regard for public opinion. After she became Orsini

gubernatrix

, Felice quickly marshalled Gian Domenico and his sister Francesca as her aides. They knew Rome well and spoke the same language as the city’s bureaucrats and merchants. Consequently they and their mother had an easy rapport with Felice’s high-ranking servants and with Statio del Fara in particular. Statio mentioned Francesca and Lucretia frequently in his letters, suggesting an easy informality existed between them: ‘Madonna Lucrezia dropped in on her way home. She asked me how Signor Girolamo [her grandson] was, and it gave her great pleasure to learn from me that he was well.’

3

Statio often worked in conjunction with Francesca, who frequently served as Felice’s agent in the acquisition of textiles and other objects. Just a few years younger than Felice, she was married to Angelo del Bufalo, a high-level Roman bureaucrat who would eventually receive the appointment of

maestro di strada

, commissioner of public works. Angelo gave Francesca connections that were useful to Felice. He was also a notorious philanderer. The churchman Matteo Bandello’s

Novelle

of

1554

tells the story of ‘Imperia, Roman courtesan...loved by an endless number of great and rich men. But among those who loved her was Signor Angelo del Bufalo, a man who was valiant, humane, genteel and extremely rich...he kept her in a very honourably furnished house, with many male and female servants continually in attendance upon her.’

4

Consequently Francesca was frequently to be found in the company of her mother and brother, undertaking commissions for her sister, rather than at her ‘humane and genteel’ husband’s side. She had a good eye, and was remorseless in seeking out hard-to-find luxury items. ‘I am dutifully letting you know that I have done what you commissioned me to do regarding those items made of gold, as well as the little cross. And if your ladyship has need of lawn, let me know as I have found some that would serve your ladyship well that is beautiful, and well priced.’

5

On another occasion: ‘I am sending you the ribbon about which you wrote to me. I have searched all of Rome, and this is the most beautiful I could find, as it is the end of the summer, and every merchant has sold the best that he has...If your ladyship does not like it, I can take it back and I shall see what I can do.’

6