The Pope's Daughter: The Extraordinary Life of Felice Della Rovere (27 page)

Read The Pope's Daughter: The Extraordinary Life of Felice Della Rovere Online

Authors: Caroline P. Murphy

Tags: #Social Sciences, #Women's Studies, #History, #Renaissance, #Catholicism, #16th Century, #Italy

Felice’s official transaction with Galeotto took place ‘in Rome, in the palace made by the late Gian Giordano, situated next to the church of Trinità dei Monti on the Pincian Hill’, the very palace that Felice was making her own. Usually, the notarization of important legal acts, such as the handing over of Felice’s dowry to Gian Giordano, or her own purchase of Palo, took place in the

Camera Magna

at Monte Giordano. But, on this occasion, Felice chose to remove herself from the Orsini seat of governance. This decision seems surprising. As ‘Guardian and Caretaker’ it would seem only appropriate for her to choose to do business from the Orsini Roman hub. But Felice was already adopting a habit of avoiding contact with her Orsini relations. It was just after Christmas; many of them were still in residence at Monte Giordano and many of those were resentful of Felice and the power that she now wielded.

Moreover, some Orsini were suspicious about the circumstances of Gian Giordano’s death. In Venice, Marino Sanuto recorded that Gian Giordano had died in Vicovaro, without confession nor communion because the doctors had not considered him ill.

5

For those inclined towards such suspicions, Sanuto’s words imply Gian Giordano’s demise was not a natural one. Although no one publicly raised an accusation against Felice, there were undoubtedly several of the Orsini willing to entertain the idea that she had had a hand in Gian Giordano’s departure from this world. Certainly the timing was convenient, with her boys aged only four and five, the thirty-four-year-old Felice’s period in office could be a long one. Yet nothing could be proved and, in any event, Felice had her indulgence of absolution of all crime from Leo X. Yet it strengthened support and sympathy from the Orsini for her seventeen-year-old stepson Napoleone, who his relatives felt should now be the rightful leader of the Bracciano Orsini. So, for Felice, negotiating the transference of power to her from the Trinità Palace, a residence built on Orsini land, but which Felice had chosen to make her own, was a calculated statement. She had never particularly wanted to make friends with the Orsini, and she had no intention of starting now. And she could not have failed to be irritated by such pompous-sounding letters as the one written to her by Gian Giordano’s cousin, Cardinal Franciotto Orsini, on

9

January of

1518

: ‘I advise your ladyship that you should wish to give a good example to others, and be attentive to not letting bad deeds go unpunished, so that our vassals are not tempted down paths where they might sin.’

6

The Cardinal implies that as a woman Felice might be overly lenient and weak with the estate workers, and was inclined to be critical of her. However, Felice and Franciotto did eventually reach an accord; bound by ecclesiastical rather than Orsini connections, Franciotto realized that alienating the new govenor would not serve him well at the Vatican court. Felice, however, continued to keep her distance from the rest of the family.

chapter 11

Felice della Rovere Orsini knew that a new role had been created for her, and with it she had become another kind of person. Over the past decade, she had acquired respect, admiration and influence, not to mention a sizeable personal fortune. However, she had always been something of an anomaly in society, her identity as a pope’s outspoken daughter was always with her, for better or worse. Now she had attained a position that Renaissance Italy could more easily understand, that of widowed regent. Many noblewomen when they became widows chose a visual commemoration of the occasion, a portrait of themselves in widow’s weeds or an altarpiece in which they could be depicted as donors. Widowhood was also the time when wealthy women bought or commissioned the building of a new home. Others performed acts of charity, founding convents or giving money to holy orders. Felice della Rovere did none of these things. She already had a collection of treasured possessions, not to mention a frescoed chapel, castle and palace of her own. She felt she had no need for further visual commemoration. Moreover, she was about to become extremely busy. Most widows who became philanthropists did so because they had two things: financial wealth and time on their hands. Although Felice controlled a good deal of money, the expense of maintaining the Orsini estate was so high that there was rarely any left over. As for spare time, until her sons, who were still only four and five, reached adulthood, her life was to be dedicated to running the Orsini estate. It did not leave Felice with a great deal of time for personal expression.

None the less, Felice did give some thought to her new position. With her husband recently deceased and her father dead for only five years, she considered how she too would be remembered when she died. In the midst of adapting to her new role as Orsini governor, she set aside some time to write her own will, a relatively unusual act for a woman of only thirty-five. Part of her decision for doing so was undoubtedly practical. If she were to die intestate, her own estate would become subsumed into that of the Orsini. Although her sons would benefit and, indeed, they were to receive the bulk of her inheritance, her daughters would be left with nothing from her. So Felice’s will, notarized on

30

March

1518

, made provisions for ‘Julia and Clarice, the natural and legitimate daughters of the testator each to receive

8000

ducats’.

1

This legacy would be in addition to whatever their dowries would be from the Orsini estate.

Much of Felice’s will, however, was concerned with the destination of her mortal remains, and the care of her immortal soul. She set aside

1000

ducats for the ‘making of her tomb and the purchase of an altar cloth’ for her chapel in the church of Trinità dei Monti. She left an additional

30

ducats to the church for the saying of perpetual Mass to her. The same sum went to Santa Maria del Popolo and Santa Maria Transpontina, for the same purpose. Santa Maria del Popolo was the della Rovere church in Rome, founded by Sixtus IV, where many of her relatives were interred. Santa Maria Transpontina on the road to the Vatican by Castel Sant’ Angelo on the papal route, was fashionable and had a large congregation. Ten ducats for obit perpetual Masses went to the churches of San Agostino and Santa Maria sopra Minerva – both in the neighbourhood of Piazza Navona where Felice had lived as a child. She also left

10

ducats to San Pietro in Montorio, the other legendary site of St Peter’s burial, and to San Onofrio, which her stepfather, Bernardino de Cupis, helped decorate. Felice’s decision to spread her money among numerous churches across Rome ensured that her name would resonate throughout her city. It was a way of ensuring her own enduring legacy and gave shape and form to the observance of her memory.

If Felice thought a great deal about her place in the divine world, she was equally concerned with the practicalities of the earthly one. One of her first tasks as Orsini Guardian and Caretaker, as laid down by the Roman Senate, was to supervise an inventory of Gian Giordano’s property. A precise record of the contents of the estate was important for ensuring that everything was intact by the time his heirs took over. Compiling a property inventory was a common duty for widows left as estate managers; a fifteenth-century Florentine fresco shows a widow standing in the middle of a room, watching as a notary records its contents. But rarely was a widow responsible, as Felice was, for making the inventory of an estate that covered several hundred square miles. This intense effort resulted in the compilation of a forty-page document detailing ‘every single movable and immovable good’ in Orsini possession. It was completed on

25

April

1518

.

2

No single document provides a better picture of what Felice had taken on when she became Orsini regent. The inventory opens with the contents of the castle of Bracciano, and with the items needed for its defence. These number over a thousand pieces of artillery, including cannons, cannonballs, gunpowder, mortar, sledgehammers, arqubusiers, lances, picks, ballasts, falconets (light guns) and ‘five huge shields, painted with a rose’, the Orsini insignia. In a striking juxtaposition, the next group of Bracciano contents listed are the furnishings of the chapel. These are very similar to those of Felice’s own portable chapel, with altar cloths, priests’ vestments, candelabra, a crucifix and two wooden angels. The altarpiece depicted

Christ before Pontius Pilate

, an unusual subject for an altar, and there was also ‘a tiny box containing relics of the

10

,

000

Virgins, the Blessed Francesco di Paola and St Christina’. Given that Francesco di Paola was only recently dead, and Gian Giordano had spent much time at the French court, this relic was perhaps actually authentic, a rare instance among the oceans of the Virgin’s milk and forests of splinters of the True Cross.

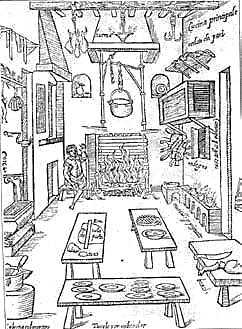

The kitchen contained copper cauldrons, and a large stove, winding spits, iron saucepans, spoons and knives, a gridiron, a large stone pestle and mortar, and a smaller marble one. Its first adjoining pantry housed a big salt cellar, numerous glass jars, some full, some half empty, with oil and vinegar, and a ‘wooden grinding mill containing yeast’. Then there were four rooms where wine was stored, catalogued in ascending order of quality. The first contained both wine and vinegar, the second fourteen ‘big bottles of Roman wine’ and ‘seven caskets’. The last

cantina

was where the muscatel, the best wine in the house, was stored.

Next was the

guardaroba

, a veritable treasure house of fabulous textiles. Here there were bed canopies made of crimson velvet, embroidered with the Orsini coat of arms, or of turquoise taffeta with a gold fringe. The older Orsini tapestries were stored here, along with the centaur series Felice had commissioned a few years earlier, and a large number of carpets. The first bedroom to be described in the inventory belonged to Gian Giordano. In it, laid out like a relic, was the set of armour he had received from the King of France, with body suit, arm bands, shoulder pads embossed with silver, silver gauntlets and silver collar piece.

Felice had no intention of her possessions appearing in the inventory of Gian Giordano’s estate, to be misidentified as Orsini property, so there is not a trace of her here at the castle. But she did make careful note of the contents of the stables, including the ‘two little bay horses belonging to Don Francesco and Don Girolamo, the sons of Gian Giordano’. In addition to the children’s ponies were six riding horses, two carthorses, three baby mules and three adult animals. There were also two carts, and a ‘four-wheeled cart, covered in black cow hide’. ‘Thirty-two large cows and two more bulls’ also lived here. Felice also listed a large pile of scrap metal, old cauldrons, spits and pans. Melted down, such goods still had intrinsic value.

From Gian Giordano’s movable goods, the inventory went on to the immovable, and to the lands and palaces the Orsini owned. This section included the compound of Bracciano itself, the castle and the land. It also listed the fief of Scrophano with its fields and vineyards and the woods of Trevignano. Galera had fruit trees, Cesano meadows and Isola cow pastures. There was a large palace at Formello, and in Rome at Monte Giordano and Campo dei Fiori. The palace at Blois built by Gian Giordano himself was mentioned, and another in Naples. The castle of Vicovaro was like a small version of Bracciano. It contents were listed, but there were not so many furnishings, and they were evidently of a plainer nature. There were no luxurious wall hangings here.

A box of documents important to the Orsini family also had its place in the inventory. Here were to be found wills, concessions from Gian Giordano’s maternal grandfather, Alfonso of Aragon, and privileges conceded to Gian Giordano by the King of France. Also included ‘in this same box are instruments, privileges and bulls, sealed by the Illustrious Lady Felice and her notary, written in various places’. The next line stated that ‘Felice, the aforesaid Guardian, has all the ingoing and outgoing expenses written down in two books compiled by her servants Carolus Galeotti and Statio del Fara’.

Documents had taken on a new importance in Felice’s life. Power was conferred on her in the form of her husband’s will and bulls from the papacy and the Senate. She in turn exercised her authority in the form of letters and mandates signed in her name and embossed with her seal. Where Felice differed from the Orsini men who had run their family estate before her was in her commitment to paperwork. Her roots betrayed her. She was not a noble, but the child of the curia and bureaucratic administrators, with all their instincts. Without such an attitude and an inherent ability, she could all too easily have lost control of her position almost as soon as she assumed it.