The Price of Glory (14 page)

Read The Price of Glory Online

Authors: Alistair Horne

At last, after about two hours that felt like the proverbial eternity, the bombardment crept towards Stephane’s little world at Company Headquarters. In quick succession, four heavy shells hit the nearby stretcher-bearers’ shelter, of which First-Aid Man Scholeck had been so proud — ‘four metres under the virgin earth, a metre for each man.’ To Stephane’s amazement, all four emerged by some miracle, clothes torn and covered with earth, but unharmed. Soon afterwards, another shell landed squarely on Stephane’s own dugout, reducing it to shambles. Barely reflecting on his own extraordinary good fortune, Stephane’s immediate thought was how aggravating to lose the balaclava helmet Madame Stephane had so patiently knitted for him.

All morning the devastating bombardment continued. Then, about midday there was a sudden pause. Suspecting that the attack was now imminent, the shaken survivors in the Bois des Caures emerged from their cover. It was just what the Germans had hoped for, all part of the plan (though neither Stephane nor his commander, Driant, could know this). Now the German artillery observers could see which strong-points, which sections of trench in the French first line appeared to have withstood the terrible 210s. It became the turn of the precise, short-range heavy mortars to administer the

coup-de-grâce

with their huge packets of explosive, while the 210s lifted to new targets further back.

At 6 o’clock

1

that morning, Driant had left his permanent HQ at Mormont in the second line for the Battle Command Post in the Bois des Caures. Before leaving he handed his wedding ring and various personal objects into the safe-keeping of his soldier servant. He had been at his Command Post several minutes already when the first shells howled down. Quietly and composedly he finished giving his orders, then went down into the shelter, where the chaplain, Pèrede Martimprey, Rector of Beirut University in pre-war days, gave him absolution. Meanwhile, from 72 Div. HQ a Captain Pujo and another staff officer from XXX Corps had just arrived in the Bois des Caures by car and were leisurely inspecting German lines through binoculars, before calling in on Driant. But no sooner had the bombardment started than the two staff officers rapidly changed their minds and took the quickest route back to Div. HQ without stopping to see Driant.

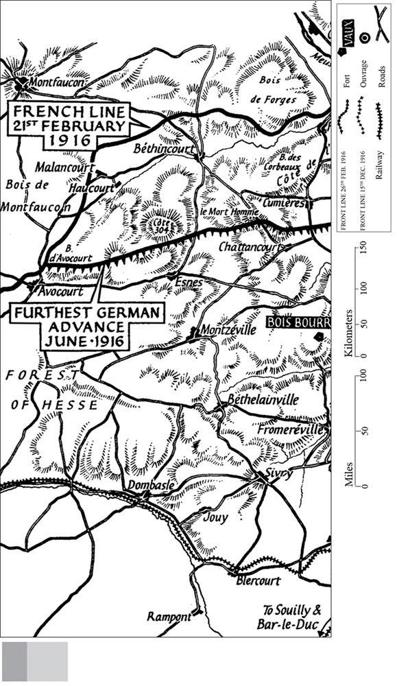

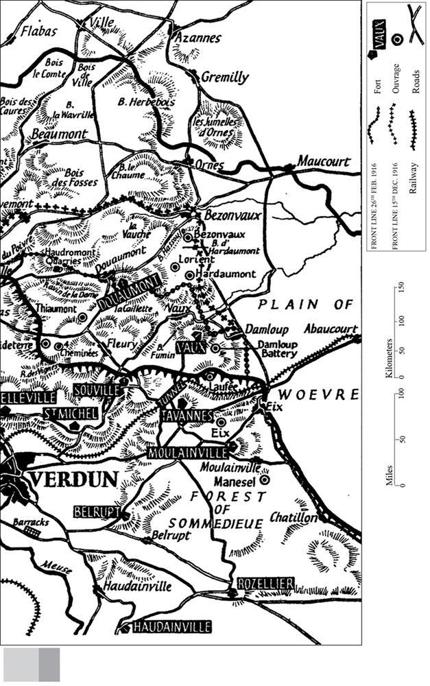

That morning, too, General Bapst himself had ridden forth on

horseback from Bras, with the intention of examining the front-line at Brabant. He had got to Samogneux, half-way, when the curtain of fire descended. He rattled out some verbal orders to Lt-Col. Bernard, commanding the 351st Regiment, with instructions to alert units at Brabant, and then returned at a full trot to Bras. Every point in the Verdun sector seemed to be receiving the same terrible pounding as the Bois de Caures, all the way from Malancourt on the Left Bank down to the Eparges well south of Verdun. In the Bois de Ville, on 51 Div.’s front, the heavy shells were falling at a frequency of forty a minute. On the Vosges front, nearly a hundred miles away a French general who was to play an important role in the finale at Verdun heard the steady rumbling and wondered what was happening. In Verdun itself the deadly work of the long-range naval guns had already seriously upset the unloading of munitions trains.

By 8 o’clock, after less than an hour’s bombardment, almost all telephone communications to the front were cut off, from brigade level downwards. One of the Brigade Commanders of 51 Div. organised an impromptu system of relay runners, each covering — if he lived that long — 300 yards. It was a form of martyrdom that was to become one of the hallmarks of the battle in later months, but under the initial deluge of steel the tenuous human linkage could hardly survive long. Nor could troop reinforcements penetrate the barrage; two companies sent by Bapst to bolster the line at Brabant only arrived, with cruel losses, when the bombardment had ended. It had taken them nearly eight hours to struggle forward some two miles. Effective command no longer existed. The German ‘boxing fire’ had succeeded even better than expected.

Behind the line, the French gunners — those that had not already been knocked out by the intense gas barrage on their positions — helplessly watched the blasting of the infantry positions. Little could be done in the way of counter-battery work, because observation was useless. The few French spotter planes to penetrate the German aerial barrage reported that so many batteries were firing it was impossible to identify them; the woods hiding the German guns were said to be belching forth in one uninterrupted sheet of flame. Nevertheless some of the long range French guns nearly did better than they knew. At Billy, well behind the lines, their first shots blew up the Paymaster of the 24th Brandenburg Regiment, with his cash-box. At Vittarville, still further off, General von Knobelsdorf was in the midst of reporting to the Crown Prince on the effectiveness of

the German bombardment, and on how feeble the French retaliation had been, when suddenly heavy shells began to fall around the Hohenzollern heir. In great haste, Fifth Army HQ withdrew to Stenay, where it remained for the rest of the battle. But apart from these two isolated minor coups, French artillery intervention was indeed practically negligible. By midday, General Beeg, the Crown Prince’s chief gunner, could report that only single guns were still functioning in most of the French batteries.

To the German storm troops in the front line, the spectacle of the whole French defensive position disappearing in the vaulting columns of smoke had an effect like champagne. In the long wait in the

Stollen

, the damp had begun to rust the men as it had rusted their rifles, but now the miseries, fatigue and anguish of the past weeks were replaced by an intoxicated elation and optimism. During the afternoon, a young Hessian of the 8th Fusilier Regiment scribbled off a last note to his mother, exclaiming, ‘There’s going to be a battle here, the likes of which the world has not yet seen.’ German aviators returning from reconnaissance over the French lines gave vivid accounts of the terrible destruction they had seen; one told his commanding officer, ‘It’s done, we can pass, there’s nothing living there any more.’

In the

Stollen

the infantry made their last preparations. The men unscrewed the spikes from their helmets, to avoid the risk of becoming entangled in the dense undergrowth of the French woods, and put on white brassards, so as to recognise each other. The officers turned their caps back to front, so they should

not

be recognised by French sharpshooters. No detail had been overlooked; every man had a large-scale sketch of the French defences opposite him, and squads of machine-gunners without their weapons were waiting to go in with the assault teams, to return to service at once any captured French weapon. At 3 p.m. the German bombardment rose to drumfire pitch; by 3.40 it had reached a crescendo, and company commanders eyed their watches. At 4 p.m. there was a cry of

‘Los!’

all along the line and the grey forms surged forward. On the left of the line a regiment of Brandenburgers went in singing

Preussens Gloria.

In sharp contrast to the British infantrymen who in less than five months’ time would be advancing in straight, suicidally dense lines on the Somme, the German patrols moved in small packets, making skilful use of the ground. For under the Fifth Army’s final orders — influenced by the cautious Falkenhayn in his desire that the battle

should not proceed too rapidly — infantry action on the first day was to be limited to powerful fighting patrols. Acting like a dentist’s probe, these patrols would feel out the areas of maximum decay in the French defences that the bombardment had caused. Only on the 22nd would the main weight of the attack go in to enlarge the holes. Two out of the three German corps adhered rigidly to this order; but rugged General von Zwehl, conqueror of Maubeuge, taking full advantage of that latitude peculiar to the German Army (and which had brought disaster to it on the Marne), decided to send in the first wave of storm-troops hard on the heels of his patrols.

* * *

Opposite the Westphalians of von Zwehl’s VII Reserve Corps lay the Bois d’Haumont, an irregular-shaped wood to the left of and slightly forward from the Bois des Caures, of which it guarded a vital flank. It had taken a dreadful pounding; by the late afternoon many of its defenders had fallen asleep in sheer exhaustion, and the remainder were in a partly stunned and shell-shocked condition. Suddenly, a soldier in a trench to the west of the wood lifted his head and noticed a line of

Feldgrau

troops less than a hundred yards away. The alarm was given, and rapidly organised French fire stopped the Germans in their tracks. At the other end of the wood, however, closest the Bois des Caures, the French 165th Regiment were instantly faced with a grave situation. Many of their trenches had been completely levelled by the shelling; their rifle barrels filled with dirt and useless, boxes of hand grenades and cartridges buried under the debris. A sector of front nearly half a mile wide was held by two platoons exhausted from digging out their comrades. When these spotted the first German patrols, they were but ten yards away, already infiltrating through untenanted parts of the line. Two posts were occupied almost without resistance, and the whole of the first line of trenches in the Bois d’Haumont fell rapidly thereafter. Up rushed the attending German machine-gun teams to man the captured weapons, and the crews with oxyacetylene torches to cut through the remaining French barbed wire. As dusk fell, the Germans had gained a first and vital footing in the French defences. Captain Delaplace, the C.O. of the battalion defending the Bois d’Haumont sent a frantic message to his Brigade Commander, Colonel Vaulet, asking, ‘What am I to do?’

At the moment when the Westphalians occupied the first trenches

in the Bois d’Haumont, the defenders in the Bois des Caures were taking stock of the situation. As the survivors came out of their holes during the second lull in the bombardment that day, they peered through the settling dust with astonishment and horror. The wood presented an appalling sight. Nothing about it was any longer recognisable. It looked as if a huge sledge-hammer had pounded every inch of the ground over and over again.

1

Most of the fine oaks and beeches had been reduced to jagged stumps a few feet high. To one soldier, they resembled a Brobdingnagian asparagus bed. From the few branches that remained hung the usual horrible testimony of a heavy bombardment in the woods; the shredded uniforms, dangling gravid with some unnameable human remnant still within; sometimes just the entrails of a man, product of a direct hit. It seemed impossible that any human being could have survived in the methodically worked-over, thrashed and ploughed-up wood. Yet some had. Like a colony of ants in sandy soil, stamped on repeatedly by an enraged child, they had been buried and reburied, yet always some — like Stephane and Scholeck — had miraculously struggled to the surface again. Undoubtedly many owed their lives to Driant’s brilliant lay-out of the wood’s defences, which, broken up into redoubts and small strongholds, had avoided anything resembling the continuous line of trenches familiar to the rest of the Western Front.