The Prime Ministers: An Intimate Narrative of Israeli Leadership (65 page)

Read The Prime Ministers: An Intimate Narrative of Israeli Leadership Online

Authors: Yehuda Avner

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction, #Biography, #Politics

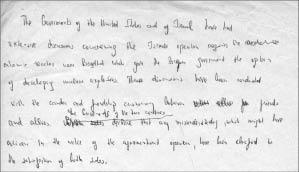

Prime Minister Begin's draft of proposed joint U.S.-Israel statement designed to end the dispute with Washington following Israel's destruction of Iraq's nuclear reactor, 13 July 1981

Photograph credit: Ya’acov Sa’ar & Israel Government Press Office

Prime Minister Begin and President Reagan in the White House Oval Office, 9 September 1981

Asset or Ally?

It was common knowledge that President Reagan had a craving for jelly beans. He started chewing them in the early 1960s when he gave up smoking, and on entering the White House he had crystal jars of jelly beans placed on his desk in the Oval Office, on the table in the Cabinet Room, in the suites of his guest house, and on Air Force One, where a special container was fashioned to prevent spillage during take-off, landing, and turbulence. The tabloids reported that guests at Ronald Reagan’s inaugural balls consumed forty million jelly beans, almost equaling the number of votes he received in the election.

“I can hardly start a meeting or make a decision without first passing around a jar of jelly beans,” quipped Reagan to Begin when they met for the first time in early September 1981. “You can tell a lot about a fella’s character by whether he picks out all of one color, or just grabs a fistful. Here, take a few.”

Begin grinned and obliged, scooping up a small handful. “In my early Knesset days, during a particularly boring debate,” the prime minister told Reagan jovially, “I would sometimes slip out to a local movie house, where I was far more entertained by you than by my parliamentary colleagues. I owe you a debt for having once chosen an acting career.” Reagan laughed. “You know,” he said, “someone asked me how an actor could become a president, and I answered, how can a president

not

be an actor?”

The jest had them both laughing. Without a doubt, his host’s genial tone and infectious bonhomie were giving Menachem Begin a sense of ease, and when the president beseeched, “Please, call me Ron. And may I call you Menachem?”

–

he pronounced it Menakem

–

Begin responded with the widest of smiles. With false modesty, he protested, “Oh, no, Mr. President,” he said, “I’m a mere prime minister and you are the president of the mightiest power on earth. So by all means call me by my first name, but I cannot call you by yours.”

“You sure can, Menakem. I insist,” said the president.

“In that case, Ron, I shall,” said the prime minister, elated.

They were sitting across from one another on floral-patterned settees in the Oval Office, two note-taking aides in attendance

–

I being one of them. The sunny rose garden was in view through the tall windows, the presidential colors were draped next to a prominent portrait of Thomas Jefferson, and dotted around the room were mementos, plaques and signed photographs

–

all the bric-a-brac of a public man who had been a middling film star and a popular state governor. Begin had arrived in Washington after a summer of political success at home

–

beating Shimon Peres to win his second general election

–

yet internationally, in this, Israel’s most important relationship, the situation had been more tense. Reagan and Begin had first clashed over the bombing of the Iraqi nuclear reactor, and then, not long after, over a U.S. sale of sophisticated military equipment to Saudi Arabia. Begin could not be certain how much of Reagan’s affability was Hollywood, and how much was sincere, but having learned that the man had a genuine admiration for Israel, and already highly buoyed by his electoral triumph, he allowed himself to relax into Reagan’s bighearted fellowship.

The first-class reception had begun an hour earlier, when the president pulled out all the stops in a ceremony of spectacular pomp and circumstance on the White House lawn: red carpet, honor guards, flags waving and bands playing. Immaculately groomed, dashingly handsome, and looking a decade younger than his seventy years, President Reagan addressed an invited crowd of hundreds, declaring, “I welcome this chance to further strengthen the unbreakable ties between the United States and Israel, and to assure you, Mr. Prime Minister, of our commitment to Israel’s security and well-being. Your strong leadership, great imagination, and skilled statesmanship have been indispensable in reaching the milestone of the past few years on the road toward a just and durable peace in the Middle East.”

Reagan then turned to address Begin directly, and the rich timbre of his voice almost cracked when he said, “I know your entire life has been dedicated to the security and the well-being of your people. It wasn’t always easy. From your earliest days you were acquainted with hunger and sorrow, but as you have written, you rarely wept. On one occasion you did

–

the night your beloved State of Israel was proclaimed. You cried that night, you said, because ‘truly, there are tears of salvation as well as tears of grief.’ Well, with the help of God, and us working together, perhaps one day for all the people of the Middle East there will be no more tears of grief, only tears of salvation. Shalom, shalom, to him that is far off and to him that is near.”80

Stirred to the core by these sentiments, so publicly expressed, the prime minister responded in kind: “Our generation, Mr. President, lived through two world wars, with all the sacrifices, the casualties, and the miseries involved. Ultimately, mankind crushed the darkest tyranny that ever arose to enslave the human soul.” This reference to Nazism was a precursor to an assault on totalitarianism, phrased in language calculated to appeal to this anticommunist crusader. Begin wanted to reassure Reagan that America could rely wholeheartedly on Israel as a faithful ally in the incessant battle against the Soviet evil: “After World War Two, people believed we had reached the end of tyranny of man over man. It was not to be. Country after country is being taken over by totalitarianism. So liberty is still endangered and all free women and men must stand together to defend it and to ensure its future for all generations to come.” And then, softly, with deep gratitude: “Mr. President, thank you for your heartwarming remarks about my people and my country, and for your touching words about my life. I am only one of the uncountable thousands and millions who suffered and fought and persisted, until after a long night, we saw the rising of the sun.”

81

All stood to attention as the national anthems were played. Had Begin used the moment to wonder how such a lavish and splendid welcoming ceremony had come about, he would probably have guessed

–

correctly

–

that Ambassador Samuel Lewis, in whom he placed much trust, had persuaded those around the president to receive Begin with full ceremonial honors, treating him as the head of an allied government, not an obdurate dependant

–

which some of the president’s men considered him to be.

The subsequent one-on-one in the intimacy of the Oval Office was in and of itself a singular gesture. It seemed to Begin that the president was deliberately seeking to break the ice in a public display of camaraderie, in order to give him the rare opportunity to open his heart and say what was on his mind in an intimate tête-à-tête. Imagine, then, his astonishment, even bewilderment, when hardly had he opened his mouth to talk about the Israel-U.S. relationship, his hopes for peace,

PLO

terrorism, the Lebanon escalation, and the stalled Palestinian autonomy negotiations, when Reagan interrupted him to say: “You must forgive me, Menakem, but we have only a quarter of an hour before we have to join the others in the Cabinet Room. So I would just like to make” – he slipped his hand into his pocket and extracted a pack of three-by-five-inch cards – “a few points. The first is….”

The prime minister stared in disbelief as the American president began reciting in a mechanical tone a series of “talking points” consisting largely of standard reaffirmations of America’s known positions on Israel and the Middle East.

This was the fifth president I had met, after Johnson, Nixon, Ford, and Carter, but Reagan was the only one who resorted to this bizarre practice of using cue cards. When he paused, which he did twice, Begin assumed it was to allow him to engage, but it was not. It was simply Reagan making sure of his lines.

Could it be that he was so uninformed that he needed to read elementary issues from cards, like a third-rate actor? All the other presidents had been in total command of their material; they needed no coaching, no cue cards. Evidently, Reagan’s advisers did not want their man plunging extemporaneously into exchanges on complex issues, for fear he would get lost in their intricacies. So Begin sat and listened. It was not an easy thing for him to do. Coming from a centuries-old culture of polemicists, analysts, conversationalists, and nonconformists, he was, by nature, a passionate debater. Ronald Reagan was destined to enter history as a brilliant public communicator, the man who reinvigorated the American people after the lackluster years of Jimmy Carter, who restored his country’s self-confidence, and who initiated policies which ultimately brought the communist empire to its knees. But little of this was evident at that first meeting, which ended with the president re-pocketing his cards and saying, “And that, Menakem, is how America sees things.” Begin responded with a gracious, “I thank you, Ron, for that comprehensive overview.”

“And now let’s join the people in the Cabinet Room,” said the president, and he led the way into the adjacent chamber. The room had colonial-style, off-white paneled walls, a brass chandelier, golden drapes, and a grand oak conference table with high-backed leather chairs, behind which senior aides were standing in respectful attendance. Mr. Begin made a beeline for the secretary of defense, Caspar Weinberger, shaking him by the hand with an affected, “Ah, Mr. Weinberger, at last! How delighted I am to make your acquaintance.”

Cap Weinberger, a diminutive man with sleek black hair, reciprocated with frigid civility, his expression a blank. Secretary of State Alexander Haig, by contrast, was an admirer of Begin, and he welcomed him with the robust muscle of the soldier that he was. The principals worked their ways around the table, Reagan extending a particular welcome to the recently appointed Defense Minister Ariel Sharon, as well as to Foreign Minister Yitzhak Shamir and Interior Minister Yosef Burg, who was now in charge of the negotiating team dealing with the long-stalled Palestinian autonomy talks.

Seating himself at the table’s center, facing Begin, Reagan extracted another pack of cards, and in the practiced style of a late-night talk-show host, suavely welcomed Begin and his entourage with the briefest but most cordial of introductions, describing Israel as “a strategic asset,” and inviting the prime minister to make any comments he wished.

Begin obliged, presenting a comprehensive review of all the relevant issues, and making reference to Israel’s role as “America’s most reliable and stable ally of freedom against Soviet expansionism in the Middle East.” Then, choosing his words most cautiously, he added, “You, Mr. President, kindly referred to my country just now as a strategic asset. While that certainly has a positive ring to it, I find it, nevertheless, a little patronizing. Given the bipolar world in which we live

–

democracy versus communism

–

the cherished values we share, and our confluence of interests on so many fundamental issues, might I suggest the time has come to publicly acknowledge that Israel is not just a strategic asset, but a fully fledged strategic ally.”

Had Begin floated this thought in Jimmy Carter’s Cabinet Room, he would have been met with a steely gaze and an icy rejection. Carter had issued explicit instructions to all his aides never to use the terms “ally” or “alliance” when characterizing the U.S.-Israel relationship. And, indeed, there were some around President Reagan’s table now who were looking faintly disconcerted. Weinberger was actually frowning. But the president continued to give Begin his fullest

attention

, and he chuckled when his guest continued with, “You know, Mr. President, I sometimes get the impression that our relationship is a little like Heinrich Heine’s famous couplet about the bourgeois gentleman from Berlin who implores his mistress not to acknowledge him while walking in that city’s most fashionable boulevard, begging her, ‘Greet me not Unter den Linden.’ I fear there are some who would say much the same to Israel today.”

On all sides, the American faces seemed either bemused or irritated, but not the president’s. He looked at the prime minister with respect, and he affirmed, “I’d be proud to acknowledge you in public anywhere, any time.”

The way he said it gave Begin the distinct feeling that this was a decent man who was both a good listener and open to persuasion. If only he would be permitted to talk with Reagan alone whenever policy differences arose – as arise they must – surely they would find a common language with which to iron things out. But scanning the faces on the other side of the table he knew that some of those flanking the president would never allow that to happen.

Encouraged, Begin continued. “Certainly, in this alliance, Israel is very much the junior partner, but a partner we are. And I dare say”

–

a faint smile curled his lips and his voice sank into understatement

–

“over the decades Israel has done a thing or two which might have contributed to the American strategic interest in our region. And much as we deeply appreciate the military and economic aid we have received over the years, I venture to suggest it has not been an entirely one-way street

–

not a charity, so to speak.”

There, he had said it: He had spelt it out. No other Israeli prime minister had quite put it that way before

–

that Israel was not merely a receiver, but also a giver. As Begin spoke he noted that Reagan was nodding in agreement. The president looked around to invite discussion, but since everyone seemed rather taciturn, Begin seized the moment to continue: “Might I suggest, Mr. President, that consideration be given to an agreed document on this matter

–

on the strategic relationship between our two countries. And in employing that expression ‘strategic relationship’ I do not mean for our own defense. We’ve defended ourselves in five wars, and we’ve never asked any nation to endanger their soldiers’ lives for our sake. We shall continue to defend ourselves if war is again thrust upon us, God forbid. What I do speak about is strategic cooperation in defense of our common interests, in a region which is the target of Soviet expansionism, more aggressive than at any time since the end of the Second World War.”

Caspar Weinberger’s gray eyes were cold as they glared at Begin. He grunted some sort of a reservation. Alexander Haig, in contrast, seemed far more amenable.

President Reagan said, “What the prime minister proposes sounds like a good idea to me. Let’s look into it.”

This caused Menachem Begin to sit up abruptly, energy coursing through him. He had been waiting for this moment for a long time, the moment when the United States of America would grant the State of Israel the status of a fully fledged strategic ally. So he said, “With your permission, Mr. President, may I call on Defense Minister Sharon to share with you and your colleagues a number of ideas which might give expression to this concept?”