The Raw Shark Texts (13 page)

“It boils down to this: if you want to study one of these creatures, territoriality is your only real hope. If you can find someone who shows all the tell-tale signs of repeated Ludovician injuries, you can find yourself a shark.”

“And that’s how you found me.”

“My employer keeps his ear very close to the ground. Your doctor is thinking about writing a paper on your ‘condition’. She showed some draft notes to a colleague.”

Randle

.

I didn’t say anything.

Nobody pushed his sunglasses up the bridge of his nose.

“There’s another problem with studying Ludovicians. Even if you can track down a decent-sized adult it’s almost impossible to keep one alive in captivity. An infant, yes, but not a mature animal. My employer is the only

person who has ever had any success with this; he once kept a fully grown Ludovician alive in a specially made containment facility for almost forty days. Since then, he’s been moving heaven and earth to find another specimen. Which, yes, is why he sent me to find you.”

I couldn’t quite believe any of this.

“You’re saying you can trap it?”

“Yes, we can trap it.”

“And take it away?”

“Yes. With your help we can capture it, take it away safely and keep it alive indefinitely.”

“Once it’s trapped, I don’t care if it’s alive or dead. Though to be honest, I’d feel safer if it was dead.”

“Yes,” said Mr Nobody. “I can understand that.”

“But. How do you know? How can you be sure it can be done?”

“I’m sure.”

“How?”

For a moment I didn’t think he’d answer.

“Because I’ve seen it,” he said slowly. “The first one, the Ludovician my employer captured, it was mine. It had been feeding on me.”

“Is it time for me to take those pills yet?”

I pulled the mobile out of my coat pocket.

“About ten minutes.”

“About?”

“Nine minutes just,” I said.

He nodded, thinking. The change in him was small but it was there. Some of the breezy confidence, the high-gloss polish had rubbed away. He seemed to sit a little lower in his chair, hunched down with his shoulders poking up either side of his neck. In this position, the blue shirt which had looked well-fitted and expensive now seemed a little baggy, hanging loose

across his chest. There were sweat marks where the material had pulled up under his armpits.

“Are you okay?”

“Fine, fine.” He straightened up but it was unconvincing, somehow he didn’t fill out his own body like he had before. “Bad memories,” he said. “It’s, well, I don’t need to tell you how it is.”

“How did it happen? I mean, if you don’t mind me asking.”

Nobody didn’t answer straightaway.

“I was a research scientist,” he said finally. “A physicist. Young, dynamic, making a name for myself, all that.”

I looked at him.

“It isn’t all lab coats and dandruff you know.”

“No,” I said. “Sorry.”

“I got myself a position with the University of London. It was a really big deal. Do you know what Superstring Theory is?”

I tried to think. “Something complicated to do with life, the universe and everything?”

“Actually, yes, more or less. It’s very exciting, very

where it’s at

. Anyway, I went to stay with an aunt and uncle down in the city. I wasn’t really at a point in my career where I could ask for the same salary as the more established academics, but my aunt and uncle had an empty attic room and they turned it over to me as a study. That’s where I did my work.” Nobody looked out across the chequerboard floor and then down at his hands. “When we first heard the noises coming from up there in the middle of the night my aunt was convinced we had a rat. You see, the work I was doing, the subject, it’s pure thought, pure concept.”

“The work you were doing?” I scrubbed my knuckles against my scalp, trying to clear my head. “You mean it attracted the shark?”

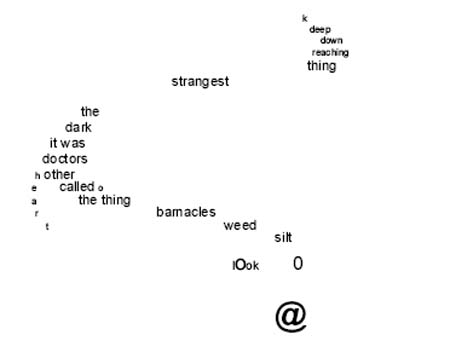

“I think it happened because there’s no physical anchor. At that level a subject like mine is essentially thought and abstracted maths. Every day, when I sat at my desk working with the figures and models, I was actually paddling that small attic room further and further out into a sea of ideas,

further away from the bricks and stone of the house. There aren’t that many people who can take a boat out as far as I could, who could get out over such depths.”

His sweating was getting worse. The wet patches under his arms had spread and new ones were forming around his neck.

“Geniuses don’t go mad,” he said. “That’s what people don’t understand. They get out so far out that the water is like glass and they can see for miles and see so much, and in ways people have never seen before. They go out over such depths, down down down and down, and some of them get taken. Something rushes up out of their thoughts, from the insides of their own heads and through the act of looking and the thinking itself – because the deep blue is in there too, do you understand? And it takes them.”

He trailed off, hands shaking and clutched around his knees.

“How long now until I need to take my pills?”

“Listen,” I said, “I’m sorry for asking. If it’s too much going over all this –”

“How long until I need to take my

fucking pills

?”

Shocked, my hand reached automatically for the mobile phone.

“Seven minutes,” I said. “I didn’t mean to upset you. I’m sorry.”

He said nothing back, just sat there looking down at his hands on his knees, his sweaty shirt clinging up under his surprisingly skinny ribs. His hair had lost some of its shape too and it stuck lank in places to his scalp and forehead. A ball of sweat striped the left lens of his sunglasses and fell away.

We sat in silence.

“I’m sorry,” he said finally, still looking at his hands.

“It’s okay. You really don’t have to talk about it. I’m just sorry I asked.”

Nobody looked up. His sweaty face seemed even more sunken, sallow, drawn than it had a minute before. He stared at me, then he just opened his mouth and – as if he were reciting something rather than having a conversation – launched into his story again.

“My uncle was a taxi-driver. If you want to be a taxi-driver in London you have to take an exam to prove you know the entire city. My uncle never

forgot a single street, never a single road. He could find every building in London but he couldn’t remember where he lived. They said it was shortterm memory damage, but it wasn’t.”

“Wait, you’re saying the shark attacked him too?”

Nobody nodded a vague nod as if the question had come from somewhere inside his own head.

“All of us. My aunt didn’t know who people were at the end. She had nightmares. A shadow in her brain, teeth and eyes. She would wake up in the night, see my uncle in bed next to her and sneak downstairs to phone the police. She’d tell them there was an intruder in the house. Sometimes she’d call them three, four times a night. Sometimes she’d get violent because she was scared.”

“Jesus,” I said. Nobody’s story, the way it was affecting him as he told it, this

deterioration

, it was hard to for me to pin it down exactly, but something was going wrong. Something here was going very wrong. My stomach felt like a loose bag of warm water.

“It happened and it kept happening, one or other of us, night after night. They came again and they checked the house for gas leaks, they checked our food and they checked the walls and they checked the ceilings for anything that could cause it, a poison. But there wasn’t anything. I had the nightmares. I saw it in my dreams. My theories were what drew it in. Numbers and maths. It wouldn’t stop coming in the night.

Who’s it going to be?

Trying to stay awake.

Who’s next what’s next what will be taken now?

By the end, being in that house. It was –”

My insides locked up and I heaved. A long slither of spit choked out of me, but no vomit. I swallowed, gagged, swallowed again. Nobody stopped talking and watched, his wet face all hollow cheeks and sharp bones behind his glasses. I wiped away the tears.

“Christ,” I said, rubbing my mouth with my shirtsleeve. “Christ, I’m sorry.”

“Yes,” said Nobody. “I’ve got to take some pills soon. Do you think you could remind me when it’s time to take them?”

“I will,” I said, trying to pull my head back together, “but I think it’s only a minute or two since –”

“I can’t take them before two o’clock,” Nobody interrupted gently. “I know you think it doesn’t matter because it’s only a few minutes. But it does. The amounts are perfectly balanced. Like seconds. Sixty seconds perfectly balanced against a minute. And dividing it up. You can’t carry a second over.”

I realised I’d put my hand in the wrong coat pocket and reached around to the other.

“You are going to come with me, aren’t you?”

“Yes,” I said, pulling out the phone.

Something here was going very wrong.

Even if the specifics kept slipping away in the mud, instinct made sure I held onto that one basic fact. I needed to get away, rest, clear my head and think. “I’ll have to go back to my hotel and pack a few things, and then –”

“

How many minutes?”

Nobody whispered, chewing on a knuckle.

He looked awful now. His shirt was a soaking, sticky mess plastered to his ribs and painfully hollow stomach. His hair was loose, lank and shapeless. Even his big aviator sunglasses looked old and dirty. And he was so wet. The sweat literally dripped off him, drops hanging and falling from his nose, his chin, the bottoms of his jeans even. Drip drip drip drip.

“Four,” I said. My hands were shaking. I couldn’t think what to do.

“You know I’m dead, don’t you?” Nobody said. “Look.” He held out a flat palm. Liquid dripped from the ends of his fingers with a steady tapping. Drip drip drip drip. “See?”

“I don’t –”

“You

do

know. All of it. It’s obvious.” Then, as if something dawned on him, he quickly swivelled around in his chair, turning his bony back to me. “Shhh, what are you doing? You’re giving away too much, giving it all away, don’t let

him

talk. It doesn’t matter. Yes, of course it matters. But I can’t keep the keel level without the pills. You’ll damn well have to keep it level won’t you because we never know what

he’s

going to say. But it’s

too long, the weave has all come apart – loose threads and holes,

he’s

showing through, you know how it gets just before the pills. I don’t care about that, I don’t care about your holes and threads, the job’s almost done you’ll just have to. Shhh, shut up, he’s going to hear.” Nobody spun back around towards me. His glasses edged up his cheeks as his face split with a huge grin of brown teeth and purpley-black gums.

“Sorry about that,” he said. “Conference call. The office. Conference conference calls. The curse of the twenty-first century.”

Liquid

streamed

off him into small brown pools around the legs of his chair.

Get out. Get out. Get out.

I shifted my weight onto the balls of my feet, slowly slowly, taking the strain in thighs and calves, ready to spring my sick body into some attempt at a run.

Nobody stared from behind his glasses.

No. He wasn’t staring. It took a few seconds for me to realise he wasn’t moving at all. Apart from the trickling water, he’d come to a complete stop. As I watched, a change began to creep across Nobody’s features; the tension slipped out of his body along with the water. His wet white face became serene and angelic, the way a face in a coffin is serene and angelic, calm and wise. His head tilted a little, mechanically.

“The important thing now is to give up,” he said, quietly. His voice was different, there was something far away behind the word sounds. “You know the truth. You know you’re already dead. Deep down you know it. Eric Sanderson’s gone, a long time gone. And Clio Aames. All of it, everything he was is over now. You should let his body go too. You should stop kicking and let it float, bob and slip all away. Let it sink down to the bottom with the quiet and the stones and the crabs. It will be alright, storms on the surface can’t hurt us anymore.”

Constant brown water flowed off the ends of his fingers and elbows as he pushed himself up in the chair. It ran from his trouser bottoms and leaked from his shoes, making dirty growing puddles that smelled of seaweed rotting in the sun.

“You don’t know who I am, do you?” his new voice said. Standing now, he gave a big bony stretch, splattering water droplets. “I’m you, of course. We’re the same dead not-person.”

I looked down and was horrified to see my own blue T-shirt wet and sticky. I battled away the un-logic of it –

it’s just sweat, you’re ill, it’s just sweat and you’re not thinking straight.

He shuffled forward a few steps, trailing brown water. I couldn’t make myself stand up. My stomach lurched and I dry-heaved again.

“I’m going to show you something now. It will be difficult for you to see at first, but what it represents is peace.”

He reached up and took hold of the arm of his sunglasses.

“Don’t,” I said. “I don’t want it. I don’t want this.”

Nobody pulled the glasses off his face.

Both his eyes were missing.

The structure was there: membrane, lens, iris, but the sense, the communication, the understanding, the fundamental eyes-are-the-windows-of-the-soul-ness of them, was all gone. Two black conceptual sockets, crawling with tiny thought-prawns and urge-worms, stared out of his face at me.

I heaved again and this time I really was sick; bile and matter and juices and oils, jellies and snots of thick green slime reeked and splattered out of me all over the black and white tiled floor.

Luxophage

The stink of sick found my mind and woke it up.

I’d passed out.

As soon as I opened my eyes, my stomach wrung itself tight again and I retched, chest pressed against my knees, folded double on the chair. I spat tangy acidy mucus down onto a pile of vomit splayed and splattered out in front of me. I grabbed at a breath before another heave forced its way out. This one was dry, a face-purpling empty retch. Another came, and another. Finally, I pulled myself upright, shaking and wiping more tears from my face.

“My employer is a scientist, I told you that didn’t I?” Mr Nobody was standing by his chair, glasses back on. He had his leather bag open and turned away to swallow tablets from a small plastic tub. “Chemicals,” he said, popping the cap back on and dropping the tub into the bag. “He can remake a person out of chemical stuffing and wire, keep them walking and talking…the miracles of modern science.” He sat down, lifting the laptop back onto his knee. Already some of the colour had come back into his face, the rivulets of water from his cuffs and trouser legs had slowed to an irregular dripping. “There are certain procedures, experiments and so on which are vital for my employer to fully study the Ludovician. As a result of these, you’ll come to rely, as I have, on certain chemical prosthetics. It’s not perfect but it

is

better than the alternative.”

The sickness tide was ebbing from my cheeks and my throat. My stomach settled a little and my mind began to clear. Everything from when I’d woken up sick in bed at the Willows Hotel to finding my

way through the hospital, to Nobody and his horrible physical and mental collapse – it all seemed fractured and out of focus. Why the fuck was I still here? It was razorblade obvious that if there’d been any sense in me at all over the past few hours, I would have made a break for it a long time ago.

“Thank you,” I said it as calmly as I could, “but I’m going to leave now.”

Nobody looked up. His eyebrows knotted behind his sunglasses and he folded down the laptop screen. I tensed myself to run, expecting something sudden and horrible; for him to hurl himself off his chair and come screaming all inhuman at me across the floor. He didn’t. He tilted his head down, moving his attention from me to the thick pile of sick at my feet.

“Oh dear,” he said, “it’s difficult when this happens.”

I leaned forward and risked a glance down to where he was looking.

Something was moving

inside the vomit.

I shock-jumped backwards up onto my feet, sending the chair skidding out behind me.

The

something

unwound itself carefully from the mucus and bile and slither-swam up into the air, coiling in loops around the vaporous remains of my thoughts and feelings of nausea. It was small – maybe nine inches, maybe the length of a worry that doesn’t quite wake you in your sleep – a primitive conceptual fish. I backed away slowly. The creature had a round sucker-like mouth lined with dozens of sharp little doubts and inadequacies. I could feel it just downstream from me in the events and happenings of the world, winding at head height, holding itself in place with muscled steady swimming against the movement of time.

I backed away further, towards the edge of the circle of light.

“The conceptual crabs, the jellies, some of the simple fish.” Nobody had put the laptop down and was moulding his hair back into something like its previous flawless style. “My employer can direct them, encourage certain behaviours. As I said, he’s an expert in the field.”

The blood thudded under my jaw, in my ears, in my eyes.

“Call it off.”

“This is a Luxophage,” Nobody said pleasantly, as if he hadn’t heard me, as if he were giving an informative talk. “It’s one of a family of what you might call idea lampreys. This particular species feeds by finding its way inside human beings and sucking on their ability to think quickly, to react. They tend to make their hosts quiet, well behaved and firmly entrenched in whatever rut they happen to be in. It’s a useful little parasite,” Nobody smiled, “although it does occasionally cause nausea.”

“That

was inside me?” I wasn’t taking my eyes off the slow-winding idea fish hanging just a few feet of separation away.

“It was,” Nobody agreed. He stood and casually closed in on the fish from behind. “We were worried you might change your mind about helping us capture your Ludovician when you saw –” He paused. “I was going to say ‘the extent of your involvement’ but what I really mean is, ‘what we’re going to do to you’.”

“Not really selling it to me, I’m afraid.” I said, still watching the fish, taking another slow step backwards.

Nobody shrugged. “That doesn’t matter. In a second my assistant here will be back inside you and you’ll do whatever you’re told.”

“I don’t –” I started, but the fish, the Luxophage, sprung suddenly to life, darting blink-quick forwards at my face. I stepped jumped stumbled tripped fell backwards, landing with a crack of shooting pain in my elbow. The little lamprey shot over my head, hitting a something, a churning thundering invisible something which pound-hammered and tumbled it away in a gigantic current. I took a careful breath and turned my head to the side. Barely six inches away, one of my Dictaphones stood like a miniature obelisk, its tiny tape winding between its spools with a low hum, the recording playing out as a sharp little clatter. The non-divergent conceptual loop. The Luxophage had swum into its flow and been washed away.

I pressed my boot heels against the smooth tiles and pushed myself across the floor, sliding on my back until I was outside the circle of light and square of Dictaphones. I sat up, cradling my throbbing elbow against my chest.

The jumbled Luxophage tumbled around the inside of the loop, once, twice, like water down a plughole, before regaining control of itself. It swam back to Mr Nobody and began circling him in a slow waist-high orbit.

“Hmmm.” Nobody’s clothes were dry again now, his blue shirt tailor-made and pressed, his hair perfect, his jeans well fitted and expensive. “That was lucky,” he said.

I forced myself painfully up onto my feet. It was lucky. The Dictaphones had saved me but for them to keep me safe, to keep Nobody’s Luxophage trapped, I’d have to leave them behind.

“I’m going now,” I said.

“No, you’re not.”

One, two, three, four more Luxophages pulled, wriggled and squirmed their primitive conceptual bodies out from behind Nobody’s big dark sunglasses. More came; five, six, seven, eight, coiling and dropping from his face. I started backing towards the archway but Nobody moved suddenly and quickly, striding to the edge of the circle of light and – stamping on one of the Dictaphones.

“No!” the word, the air came out of me like a wound.

Nobody smashed his heel down hard again and the little plastic casing split, cracked and broke apart. The sickly ball of lampreys around him buffeted and bobbed as the conceptual loop collapsed in on itself and was gone. The ball unribboned and Luxophages launched themselves at me in a wet black hail of guilts and phobias. But with half the distance covered, the swarm went haywire. They looped and jumbled in a mad dance of eights and zeros before disappearing through the ceiling and walls and floor and up under the window blinds. One shot back to Nobody, circled him in two quick loops and vanished with a splatter of panic into a broken strip light overhead. In an instant every one of them had gone.

I thought

they’re going to come back at me from all directions

, but even as I thought it I knew it wasn’t true. This wasn’t hunting. It was more like the way a shoal breaks up when a diver or a –

I looked over at Nobody. The confused look on his face turned into panic.

When a diver or a –

With a deep deep horror I realised what was happening.

“You idiot!” I screamed, before I could help it, all my fear of Nobody swallowed up by something greater, more terrible, more familiar. “It’s here.

It’s been waiting. That loop was the only thing keeping us safe and you’ve destroyed it. You fucking fucking idiot.”

Nobody opened his mouth to speak but changed his mind.

Clarity and silence came.

I stood statue still, listening, feeling for any sign of it and trying not to make myself obvious. I wanted to run, more than anything I wanted to run, but that would mean splashing, churning the flows and spreading the scent of my panic and fear out through the waterways. All I could do was stay still and try not be seen.

A distant thud inside my mind and inside the hospital at the same time.

‘

Ludovician

,’ Nobody mouthed.

“You said you could capture it,” I whispered, painfully loud in the quiet.

“Not,” he said, “not without – I need a team, and equipment. It isn’t possible without –”

The circle of lamplight

rippled

the way tea ripples in a teacup. Nobody stopped mid-sentence and took a careful step back from the edge. “Territoriality,” he said. “It’s you it’s come for. You, not me.”

It’s come for me

. I started to focus on my Mark Richardson personality, felt the tensions and weight of expression changing on my face. This close-up it might not be enough to hide me, but it was something. I had to try.

“What about the things you said about us being the same person?” I said, pushing the Mark Richardson attitude out in front of me like a shield.

“What?” Nobody backed further away from the edge of the light. “I didn’t say that. Why would I say we were the same person?”

I felt my eyebrows come down. “You said –”

There was another bang, louder this time. The bow wave of something large and just out of sight washed through the light circle, distorting the geometry of the black and white tiles with rolling dips and waves.

“Oh, Christ.” Nobody held onto the neck of the standing lamp with one hand and circled slowly around it, looking out into the dark.

Mark Richardson

, I focused with everything I had.

Mark Richardson Mark Richardson Mark Richardson

.

“So far out,” Nobody was saying quietly to himself and I could hear his feet stepping around and around the lamp. “So far out. The beauty of it, the simplicity. So big and so deep. Over such depths. The things I. The things I –”

He screamed a high-pitched and horrible scream.

I thought he’d dropped onto his knees but he hadn’t – his left leg had been pulled

through

the black and white tiled floor up to the thigh. The ground stayed solid and real under the rest of his body – his hands and elbows pushing and scrambling against it and the foot on the end of his stretched-out right leg kicking and squealing against the varnish – but his left leg had passed down into the tile and concrete as if the ground were completely insubstantial.

His thrashing body made a single powerful downwards jerk.

He became silent and still. He gulped, spat, gulped again. His head lolled.

“Oh, God,” he said.

For a few seconds he just hung there, then – another jerk. His mouth opened to scream and his entire body vanished under the floor.

The standing lamp rocked from side to side on its wide round base, stretching the circle of light into a swinging yellow oval – back and forth and back and forth. The white tiles flushed red for a moment in an under-the-ice plume. The colour dispersed in swirls and was gone. The lamp slowed its rocking – back and forth and back and forth. The circle of light steadied, stopped.

Everything was still.

I was alone.

I screwed down my eyes again –

Mark Richardson Mark Richardson Mark Richardson

. But the fear had me shaking and my lips juddered out sound as I thought the name over and over in my head. “Mmm,

mm–mmm.” Trying not the think about the floor, trying not to think about the solid flat surface abandoning me and my being dragged down into deep waters. “Mmm, mmm–mmmm.”

A hand landed on my shoulder.

“Shhh,” a girl’s voice said, close behind my ear.

I froze.

“Do you still smoke those horrible menthol cigarettes?”

“No. No, I –” Babbling not thinking. “No, I don’t –”

“Well, you do now.”

Another hand reached around me and pushed a lit cigarette into my mouth.