The Raw Shark Texts (24 page)

He looked around himself and, seeing a cushion against the far wall, motioned for me to bring it over and sit. I did, putting the carrier bag down and crossing my legs next to him.

“We all have a lot of work to do tonight, but I think it’s important that before tomorrow, you understand what you were, what you are.”

I looked across at him, the candles reflected themselves in his glasses.

“When you – when Eric Sanderson One came to me he was damaged and heartbroken and obsessed. I should have turned him away but I was damaged and obsessed too and I thought, if I can just live long enough to pass on the lessons. I should never have given you such dangerous knowledge but I was running out of time, there was no one else to teach and no one else to do the teaching. I was the last of my school, Eric Sanderson Two.”

I thought about all the survival tactics and tricks the First Eric had sent to me in his letters. He told me he’d learned them all from Fidorous, but now I realised I’d never given any thought to where the doctor himself might have learned them. Of course, of course there was too much here to be the work of one old man.

“For a very long time,” Fidorous said, “there existed a very

discreet

society, a school of logologists, linguists and calligraphers. When I joined them, they were called Group27, but before that they were The Bureau of Language and Typography. The name has changed many times through the years but originally they were known by the Japanese name Shotai-Mu.” He stopped, thinking. “You should know you’re part of a very long story, Eric Sanderson the Second, the final part. What happened to you happened because I convinced myself I could pass on the knowledge you were looking for

and

turn you away from your obsession. Of course, I couldn’t.” The doctor sighed. “Endings and beginnings,” he said quietly. “The ending to the story of the Shotai-Mu is here in this room; the old man in his pile of words and the apprentice who lost his mind. But our beginning, the beginning of all this is a much bolder and brighter place.”

In the room with the flickering candles, Dr Trey Fidorous told me this story.

ONE

History tells us that it was the monk, Eisai who introduced Zen to Japan, but before that time there were a number of other enlightened Japanese who had travelled to China and studied Zen under the old Chinese masters. Tekisui did not travel to China to learn Zen. He was a keen student of art and history, and went to China for those reasons. It is said he spent many years studying the Chinese calligraphy of very ancient times before becoming a pupil of Hui-Yuan, who was one of the greatest Zen teachers of the era. Tekisui studied under Hui-Yuan for fourteen years before returning to Japan.

When he returned, Tekisui lived in a deep and wild valley where he would spend all his days meditating. When people sought him out and asked him to pass on the teachings he had received, Tekisui would say very little or nothing at all to them before moving to a deeper, even more inaccessible part of the valley where he would be found less easily.

This was in a time when the great temples had lost much of their influence and Japan was under the military rule of the Bushi, great warrior families who in later times would come to be known as the Samurai. Tekisui’s valley was part of the territory belonging to a powerful Bushi warrior named Isamu. Isamu’s family had fought against the Bushi of the temples and against Japan’s noble families to help establish country-wide military rule under Minamoto no Michichika. Isamu was known and respected across the whole of Japan. When Isamu heard about the monk who lived in his valley, he sent an invitation to Tekisui asking him to come to see Isamu. Isamu had three sons – there was Kenshin, who was the oldest, Nibori who was the second oldest and Susumu, who was the youngest. Each son was well known across Japan as a hero and great warrior in his own right. All three sons returned to their father’s house the night of Tekisui’s visit to hear what the monk might say.

When the time came, Tekisui arrived as invited and stood before Isamu and his family. He took a writing brush from his robe and drew a single straight line in the air. This was the beginning and end of Tekisui’s teaching. It is said by some that Isamu was instantly enlightened in that moment, but this story is not true. Isamu was not enlightened, but he was wise and did not give his opinion too quickly on any matter. Isamu’s sons were furious however because they believed Tekisui had made a joke at their father’s expense. Susumu said he would punish the monk for his lack of respect and drew his sword. Susumu was a well-known swordsman and had fought many duels but Tekisui remained in place, holding his paintbrush. Susumu attacked but Tekisui used his paintbrush and defeated him in three moves.

Nibori, the second oldest son, drew his sword and said, ‘My brother is a great warrior, but you should know I am even more proficient.’

When he heard this, Tekisui said, ‘Then I must prepare accordingly’ and he plucked a single hair from his paintbrush. He placed the brush on the ground and held the single hair up in front of himself. Nibori attacked and Tekisui defeated him with his single hair in two moves.

It was then that Kenshin, the oldest son, drew his sword. Kenshin said, ‘I must tell you that I have never lost a duel. Except for my father, I am the greatest swordsman in this region.’

Tekisui replied, ‘Very well. I will prepare as you have suggested’ and he placed the single hair on the ground next to the paintbrush and held up nothing in front of him.

Kenshin attacked and Tekisui defeated him with nothing in one move.

After this had happened, Isamu said that he was amazed by Tekisui’s skill.

Tekisui said, ‘What you have seen is the idea of skill, or un-skill. It is everything and nothing, a picture, a lantern, a grain of sand from a distant seashore.’

Kenshin, Nibori and Susumu apologised for their ignorance, and Kenshin asked if all three brothers could return with Tekisui to his valley

as his students. Tekisui agreed and in this way, the school of Shotai-Mu was begun.

Many years passed and Isamu became an old man. In all this time he did not receive a visit from his sons. Isamu was saddened by this, but was not angry because he had seen Tekisui’s learning and was pleased that his sons were able to study with him. Isamu also knew that the Shotai-Mu valued silence and isolation highly, and that it was for this reason that Tekisui had not built a temple or library, but had instead sunk his new school deep into the earth at the bottom of his valley. Isamu decided it would be for the best to leave his sons to their studies.

One night a merchant caught in a thunderstorm came to Isamu’s door. Isamu instructed that the man receive shelter for the night and to show his gratitude the merchant gave Isamu a rare calligraphy scroll as a gift. What neither the merchant nor Isamu realised was that one of the characters written on the scroll was bad. Not only this, but the scroll had become wet in the downpour and the water had woken the bad character up.

Over the many months that followed, the bad character sickened Isamu’s mind, causing him to become confused and forgetful, and to behave in a way that made him a stranger even to his own household. Eventually, troubled Isamu passed completely into unconsciousness.

At this time a messenger was dispatched to Tekisui’s valley to inform Isamu’s sons of what had happened and to ask Tekisui and Shotai-Mu for help.

Three men arrived at Isamu’s house at dawn on the next morning. These men were dressed as Bushi warriors but they were unlike any Bushi ever seen before. Their bronze armour was made from tens of thousands of intricately moulded symbols and characters, and appeared so thin and delicate that even a glancing hit would slice through it easily. It was also seen that instead of the two swords usually worn into battle, each warrior

carried only one, a sword with a hilt but no blade. These warriors were Isamu’s sons: Kenshin, Nibori and Susumu; but they went unrecognised because their long absence and many years of study had changed them greatly.

The three men entered Isamu’s scrollroom and fought against the bad character. They eventually defeated it but Susumu was mortally wounded in the duel. Kenshin and Nibori were urgently recalled to Shotai-Mu later that day but Susumu did not have long to live and said he would spend his last hours in his father’s house.

Isamu woke in the evening and his mind was restored. Instantly he recognised the dying warrior as his son. When Susumu opened his eyes and saw his father he asked that from then onwards all the written characters used in the region be sent to Shotai-Mu to ensure that they were not bad. Isamu quickly agreed to this and made the further promise that he would do all in his power to see that every written character in the whole of Japan would be seen by the Shotai-Mu. On hearing this, Susumu smiled and passed away.

The promise was one the old man would live to keep.

The Cube of Light

“There’s something I want you to see.” Fidorous did his headmaster walk down the corridor and I followed along behind. “When the First Eric Sanderson found me,” he said, “I was wounded, running and in fear for my life. I’d been trying to blur my conceptual tracks with a smokescreen of codes and texts, running from city to city.”

“The path Eric followed to find you?”

“Yes, but it wasn’t working and I couldn’t move fast enough. Eric helped me gather materials to build a trap.” We came to a door in the book wall. “He saved my life. That’s why he took it so badly when I wouldn’t help him find a Ludovician.”

“A trap to trap what? What were you running from?”

“I’m just about to show you.” Fidorous swung the door open.

The space behind was cavernous, dark and indistinct, like an aeroplane hangar at night-time. I stared. Out across the floor stood a house-sized cube drawn entirely in flickering light.

“God,” I said, staring. “It’s beautiful.”

Fidorous didn’t answer.

As my eyes adjusted I saw the effect was made possible by a collection of tall wooden frames. Each of these supported one or more film projectors and each projector shone onto the side of a neighbouring projector. Together they described the cube.

“That’s the trap?”

“Yes. Signifier filtration at the top,” Fidorous said, gesturing towards the upper part of the cube, “and containment down here at the bottom. It’s a cage. A fish tank.”

Looking back, I began to find the impression of a great dark ball swarming at the tank’s heart. Long fat coils of guilt, fear and defeat would bulge and loll from the churning mass then suck or slip back inside. Worst of all, the dark ball felt familiar, an unbearable sickness of weight and dread.

“What’s inside there?”

“A Gloom.”

I turned to look at the doctor.

“Luxophages, Vigophages and Aptiphages,” he said. “Thousands of them. And the big ones at the heart are Panophageus, the shoal queens. A colony like this is called a Gloom.”

A revulsion shudder. I thought about the Luxophage that had been inside me at the abandoned hospital, the sickness, the lack of direction and will. I thought about Mr Nobody and his employer.

“Where did it come from?” As I asked, I could already feel the answer forming in my head. I began to sense the beginnings of a vast circle.

“Mycroft Ward,” Fidorous said.

I stared back at the tank. “Why?”

“Shotai-Mu tried to stop Ward’s spread. We fought a war against him for almost twenty years. One day his agents broke our computer security. They had been breeding Glooms and they loaded dozens of them, millions of individual fish, into letters and words and then fed them into our language monitoring system.” The old man looked dazed, empty. “I was the only Shotai-Mu to survive, and only then thanks to you.”

“You came here.”

“This department had been abandoned a long time ago and Ward’s people didn’t know anything about it. You see, I’d always thought that my priority must be the continuation of our work. I did what I could to keep myself hidden as I cared for and maintained the languages. But. But I’m old now and Ward has made himself rich and powerful. He has the resources to ensure that one day he’ll perfect his standardising system and if that happens, instead of a thousand Wards there will be a hundred thousand,

a million, a billion. He’ll grow exponentially until there’s nothing and no one else left. Just Ward, Ward, Ward in every house, in every town and every city, in every country in the world. Forever.”

“Jesus,” I said.

“And that,” he said all matter-of-fact, “is the reason I’m helping you both tomorrow.”

Orpheus and the QWERTY Code

It took about ten minutes to get back to the First Eric Sanderson’s room, the doctor taking time to show me a small kitchen and bathroom along the way.

After all the corridors and junctions it was good to arrive back at Eric’s door, good to know my things, my cat and a warm comfortable bed were on the other side.

“How long is it since you slept?”

“I don’t know,” I said. “I just feel sort of dazed.”

“Hmmm. Well, I’m afraid there are two important tasks to be completed before the morning.”

As he spoke, Fidorous lifted a very old paintbrush from his inside pocket. The wooden stem was worn dark and shiny with ancient ink and what looked like it could have been centuries of polishing grease from fingers and hands. The bristles were dark too but unclogged and perfectly shaped.

“Like Tekisui’s,” I said. “It’s a calligraphy brush, isn’t it?”

“Yes, it is, and you have to use it to write your story. As much of it as you can remember and in as much detail as possible.”

“Write it where?”

“In the air.” Fidorous made a gesture in empty space like someone signing their name with a sparkler. “By the morning, this brush must have written your entire story. Do you understand?”

His blue eyes were calm, clear and serious as he held out the brush.

“Yes,” I said, surprising myself. I took hold of ancient wooden stem carefully. “You said there were two things?”

“You also need to drink this,” he produced a small glass from a jacket pocket. I took the glass from him and held it up to the light. It was full of thin paper strips, as if an A4 sheet had been shredded and then chopped again to make tiny oblongs. When I looked closely, I saw that each strip had the word

WATER

printed on it in black ink.

I turned back to the doctor. “Drink it?”

“Yes, you have to drink the

concept

of the water, to be able to taste it and be refreshed by it.”

“How am I going to do that?”

“There are two types of people in the world, Eric. There are the people who understand instinctively that the story of The Flood and the story of The Tower of Babel are the same thing, and those who don’t.”

I was about to speak but –

“You must have drunk the water and written your story by tomorrow morning. I’ll come back to collect you then.” Without waiting for a reply, the doctor turned and headed off down the corridor. I thought about shouting after him but I delayed a few seconds, waited too long, and then he was gone.

Ian wasn’t too pleased when I turned on the bedroom light. He had the expression big tomcats sometimes have when they’ve been poked awake for a family photograph.

“Sorry,” I said, sitting on the edge of the bed.

Ian’s ear went

flick.

I picked up the glass and poked around inside it. The paper strips made a swishing hissing sound as my finger disturbed them.

Conviction

. I closed my eyes and tried to convince myself that the swishing was the hiss of water running through a long hollow pipe. When I’d got the thought fixed as firmly and intently as I could, I took my finger out of the glass and tipped it up against my mouth. The papers rolled up against my lips in an

airy ball-chunk, a few dry tickly strands finding their way to my teeth and tongue. I opened my eyes, picked and spat them out one at a time, rolled the last one into slightly pulpy ball and flicked it away.

I stared into the glass for a while. The little white paper strips sat tangled together each one with the word

WATER

showing or half-showing, or not showing at all. I vaguely remembered something about a small vial of powder that turns into blood when enough devoted religious people stare at it.

The wine becomes the blood of Christ

came into my head from somewhere and I thought

Oh great

.

Conviction. Conviction. Conviction

. I picked up the glass again and knocked it back, opening my mouth wide and fully expecting the taste and feel of water to come flooding in all cold and heavy. Instead, the paper tumbled down and my mouth became a hamster cage. I spat the strips out into the glass, some wet and sticky with mucus strings. At least one stuck to the roof of my mouth so far back it was almost in my throat. I poked my finger in, trying to peel it away with my nail, almost retching.

I put the glass down on the bedside table. The idea of water? If the seams between the physical and the conceptual were there, I couldn’t find them let alone start unpicking, so instead I took up Fidorous’s ancient paintbrush.

You have to write your story with this. As much of it as you can remember and in as much detail as possible.

I stood up.

The paintbrush pointed out level and steady.

I began.

I was unconscious. I’d stopped breathing…

Holding your arm out in front of you for any length of time takes much more strength than you might expect.

I finally put the paintbrush down onto the bedside table and rubbed my face with my hands. The whole thing had taken – how many hours?

Two, three? Hard to tell in a world of electric lighting but I’d done what the doctor asked, written out my story into the air. I felt sick. I hadn’t eaten for a long, long time and although I wasn’t especially hungry, I knew the sick feeling would only go away if I found myself some food. I started to need the toilet too and it occurred to me that whatever I might be going through, the mechanics of my body would only ever run silently in the background for so long. There was something reassuring in that, the repetition, the

anchor

of it. Shaking out my aching arm to stop it cramping, I headed for the bedroom door.

I flushed the toilet and washed my hands, thinking absently about a shower in the small yellowy cubicle in the corner of the room but also knowing I was too tired, too dead on my feet; the edges of my thoughts were already fluttering out of the reach of my sluggish shutting-down brain. I needed to eat and collapse; everything else would have to wait.

I left the bathroom and went around the book corridor corner to the kitchen door.

It was open, the blue of an electric striplight shining a stripe across the floor and up the book spines on the opposite wall. I heard the sounds of a kettle, a coffee spoon rattling in a mug. I leaned around the door-frame.

Scout

. Something – my nerves, my blood – jumped and froze at seeing her, a fountain turning to ice and static inside of me.

She saw me before I could pull my head back, her thumb coming up and wiping under her eyes as she turned away.

“I didn’t hear you coming,” she said.

“The corridors.” I didn’t know what to say. “The books on the walls dampen the sound down, I think.”

She nodded, facing the kettle, waiting for it to boil.

We both stood there. Slow seconds ticking.

“How’s it going?”

“Alright,” she said. “I think I’ve got the laptop connection stabilised.”

I nodded even though she couldn’t see me. “That’s good.”

“You know what,” she said, “can we just not do this?” She turned

around and her eyes were glassy and drawn under in red where she’d been crying. “I’m tired and I’m trying to stay awake and concentrate and anyway, I don’t need to

pretend

to give a shit about you anymore, do I? Remember? That’s right, isn’t it?”

“You’re the one who lied.” A childish thing to say. “How am I supposed to – ”

“That’s right, because you know everything, don’t you? You know everything I’m thinking and feeling.”

Something cold inside me said, “I know the facts.”

“

I know the facts.

” She shoved her unmade coffee away. “Just fuck yourself, alright, Eric? Just go and fuck yourself,” and she pushed past me, out of the room.

On my own, staring at the floor, standing in the doorway.

At some point, the bubbling kettle turned itself off with a loud click.

Above the word tunnels, at the corridor edge of the

library’s underground stacks, a great and streamlined

notion glides slowly to a stop. It tips and bobs slightly

in sluggish event-currents created by occasional librarians

and visiting scholars. The mouth of Occam’s razors and

malice of forethought gapes and then closes. Slashed ellipsis

gills flush and flare. The Ludovician’s eye is a void-black

zero, a drop of ink, a dark hole sunk deep into the world.

The thought-shark seems to be listening, or thinking.Somewhere down below, my eyes flicker in dream-sleep.

Nightmares.

I woke up with a jolt, panicking at the unfamiliar covers over me and the blur of a strange ceiling up above. And then I remembered where I was.

The First Eric Sanderson’s bedroom

. My muscles relaxed. I tried to chase after the dream, get a look at it, but it was already gone, evaporated and forgotten like so many others.

What time was it? The light I’d left on glowed the exact same yellow as before and it could have been any-when, seconds or hours after I’d finally climbed into the bed. The days and the nights were meaningless here, replaced with switches and a steady electric forever.

I thought about the yellow Jeep, the rain, the air.

“You’ve missed something.”

I shuffled up onto my elbows, peered down the line of the duvet to see someone sitting at the bottom of the bed. Fidorous.

I’d crawled under the covers still dressed so I swung myself slowly up into a sitting position.

“What?”

“In these books, you’ve overlooked something. It really is very clever.”

I tried to shake focus myself. Fidorous was reading my Light Bulb Fragment books.

“Hey. You can’t just walk in and go through my stuff.”

“I didn’t. You left it behind last night.”

He was right. I’d forgotten the plastic bag, left it in the room with the table and the candles.

“It still doesn’t mean you should be reading them.”

The doctor’s eyes settled on me. Always so clear and empty, there was no way to tell what might be brewing behind them. I felt the smallest twist of anxiety.

“So, you don’t want to know what it is you’ve missed?”

Still foggy and drowsy, I lifted my hand, half wanting him to give me the books and half preparing to snatch them. The result was a

not quite anything

gesture which wasn’t strong enough to get either thing

done, especially as I really did want to know what he was talking about.

“This QWERTY code,” the doctor said, ignoring me. “Your notes here, and here, and, yes, here, suggest it’s random. I’m not sure it is.”

I rubbed my fingers through my hair as if the extra static might help fire up my brain.

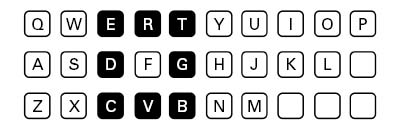

The QWERTY code was part of the encryption used on The Light Bulb Fragment text. In one big mouthful, it meant that a correctly decoded letter could always be found adjacent to the letter it had been encoded as on a standard QWERTY keyboard layout, like this:

Here, the encoded letter is an F, so the correctly decoded letter must be either E, R, T, D, G, C, V or B. As the first Eric Sanderson wrote, there didn’t seem to be any pattern which might predict which of the eight possible letters would turn out to be the correct one and this made the decoding process very slow and painstaking.

“You mean you think there’s a system?”

“Yes,” Fidorous nodded. “But that’s only the tip of the iceberg. Look.” He took a pen from the inside of his jacket pocket and found a clean page in one of the notebooks. “The very first letter of the whole Light Bulb Fragment is the C from ‘Clio’s masked and snorkelled head’, correct?”

“Yeah.”

“But before you applied the QWERTY to decode it, your notes say this letter was originally a V – ”

“ – meaning the correct letter was one space to the left of the given letter, yes?”

“Yes.”

“So we take our pen and we draw a horizontal arrow running from right to left, like this:”