The Raw Shark Texts (25 page)

“Okay.”

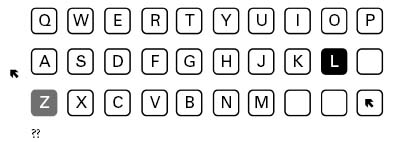

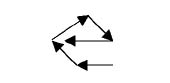

“The second letter you translated was the L in Clio, but originally this letter appeared as a Z. It gets a bit tricky here because of the way the letters roll around at the edges, but the connection works like this:”

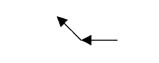

“From Z to L is effectively a diagonal up and left move, so, going from where we finished the first arrow, we draw another, this one going diagonal up and left, like this:”

“With me so far?”

Groggy, I was straining to take any of this in. “Completely with you,” I lied.

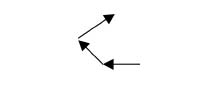

“Good. Almost there. The third letter you translated was the I. Originally, this appeared as a J. The I is diagonal up and right from the J, so our next line goes like this:”

“The fourth letter is the O. This was a K originally. This is one of the few letters we have a choice with. We can either draw another line going diagonal up right or, with the rollaround, we can decide to draw a line going diagonal down right. Let’s choose down.”

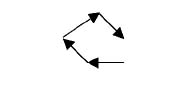

“Now the ‘D’ decodes into the ‘S’. That’s a horizontal left to right…”

“There. So what do you see?”

I looked at the page and the ground shifted inside my head.

“It’s a letter. The letter e.”

“I thought so too. The system isn’t perfect – as you’ve seen there are a few lines which can go one of two ways – but with a little work it should be possible to understand how the letters have been formalised and recognise each of them as they appear.”

“So wha –”

“Well, if I’m right, this QWERTY encryption doesn’t just encode a single piece of writing, it meshes two together. What you’re looking at is the first letter of a second text, smaller but quite distinct from the first.”

“So there’s more to The Light Bulb Fragment?”

“Yes. At least, there’s certainly more of

something

.”

I stared at the letter made from biro arrows.

“Unfortunately,” Fidorous said, closing the Light Bulb books and handing them to me, “we can’t give this any more time now.”

“Doctor, if there’s more text here, I need to know what it says.”

“I’m afraid events are already catching up with us. Scout has stabilised a connection between the laptop and Mycroft Ward’s online self. We have to get underway.”

I tried to say

get underway where?

but I didn’t get a chance.

“Now, how did you do last night, with the water and the brush?”

“I finished with the brush,” I said, “but the paper in the glass is still just paper. There’s – I didn’t know how to make it happen.”

“Hmmm. Where’s the brush?”

I found it and passed it to Fidorous. He weighed it in his hand, thinking for a moment. “You’re sure you wrote everything out with this?”

I nodded. “I was doing it for hours. I didn’t get to sleep till – what time is it now?”

“Eight o’clock.”

“I’ve had three hours’ sleep.”

“Well,” the doctor tucked the brush away in an inside pocket. “That will have to do. Bring the glass with you. You’ll just have to keep working on it at the

Orpheus

.”

“The

Orpheus

?”

“Our boat,” the doctor said, getting to his feet. “Use the bathroom and pack whatever you need to pack. I’ll be back for you in fifteen minutes. Make sure you bring a coat and those Dictaphones too, we might well need them.”

With my hair still wet from the shower and wearing combat pants, boots and a heavy, high-collared jacket from First Eric Sanderson’s room, with the Light Bulb books and all my other finds in the rucksack on my back, with the glass of papers in one hand and a carrier bag full of Dictaphones in the other, I followed Fidorous through book-lined corridors.

“What about Ian?”

“Your cat already found his way down there. He’s a curious sort of animal, isn’t he?”

“You said you’ve got a boat in here?” Tired and overloaded, I was getting past the point of being surprised by anything.

“You’ll see, not far now.”

A few minutes later, our corridor ended in a staircase leading down to a door.

“This is the dry harbour,” Fidorous said.

We stepped out into a supermarket-sized cellar with a flat concrete floor, a high ceiling and row after row of light bulbs hanging on long spiderwebbed cables.

Scout was there. She was working on something in the middle of the space.

Come on

, I told myself.

This is it. This is how it all finishes, one way or the other. You just have to be strong for a little while longer

. I followed Fidorous out onto the floor.

Scout was wearing a heavy blue waterproof coat I hadn’t seen before. It looked like she was making something, a big something, some sort of floor plan from planks and strips of wood, with boxes and tea chests and

other odd bits and pieces carefully arranged inside. I recognised Nobody’s laptop standing on an upturned plastic crate in the middle of the assemblage. A cable, presumably the all-important internet connection, unwound from its back and disappeared up into the ceiling. I spotted five other computers too, ancient 1980s models with thick cream plastic casings. One of these computers had been placed at each corner of the floor plan, like this:

Two things hit me about that layout. I didn’t know which realisation rocked me harder.

“Those white computers,” I said, “they’re for creating a conceptual loop, aren’t they?”

“Correct, an extremely powerful one using streaming data instead of recorded sound.”

“And,” I said, “they’re arranged in the shape of a boat.”

“Yes, they are.” Fidorous swept out his arm in the direction of the assemblage. “Welcome to the

Orpheus

.”

Scout glanced up from a nest of plugs and adaptors then turned away.

“Come over, come over,” the doctor said, leading me towards the collection of things laid out on the floor. “Take a closer look.”

I hesitated.

“There are gaps at this end,” Scout said, straightening up. Hearing her speak made something alive jerk in my throat but she looked calm, unruffled, as if last night hadn’t happened. “Doctor, do you reckon you’re going to need more wood for the back?”

Fidorous must have been totally caught up in the idea of the assemblage because he seemed completely wrong-footed by the sudden thickness of the air. “Yes,” he said, after a second. “Yes, I think more wood would be useful.”

“Okay then, I’ll see what I can find.” And then she turned towards the door.

The doctor watched her until she’d left the room and then he looked at me but he decided not to say anything.

“What is it?” I said, walking towards the assemblage, trying to change the subject.

“It’s a boat,” Fidorous said, catching up with me. “A shark-hunting boat.

The

shark-hunting boat you might say. Come this way around, I’ll show you.”

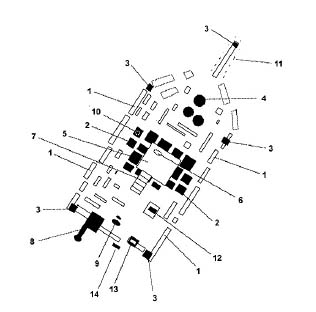

1. Planks. The outline of the

Orpheus

mainly described in flat planks of wood. More planks had also been placed inside this outline to fill empty spaces. The planks were a mixture of fresh wood and old floorboards, shelves, skirting boards, slats, windowsills, parts of door panels etc. Some planks were old and fossilised under layers of chipped white gloss paint, some holed and marked where bolts and fasteners had once been, some snapped and rough and splintery, and some new and smelling of sweet sappy sawdust. Pieces of hardboard, plywood and chipboard had been included, but basic wooden planking made up the majority of the floor plan.

2. Boxes. A large oblong central section of the floor plan had been built up to about waist height with a collection of boxes. These included cardboard boxes, tea chests, plastic packing crates etc. Most of the boxes appeared to be empty but there were several exceptions to this: a box which had once been the packaging for a small fridge was now loaded with cookbooks and a large tea chest had been plastered on the inside with pages from an interior design catalogue, while another contained greasy machine parts, cogs and a car battery.

3. Computers. Five blocky, 1980s computers positioned at the five corner points of the assemblage. Every computer had been connected to its two immediate neighbours with white phone cables and together these created a boat-shaped conceptual loop following the edges of the plank outline. Each computer also had a black power cable which led to the tea chest containing the car battery. All the computers were switched off.

4. Barrels. Three large, sealed, clear plastic barrels stood near the front of the assemblage. The barrels had been filled with Yellow Pages phone books and other telephone directories along with sticky wads of Post-it notes, address books and several Filofaxes. Each barrel also contained two or three black plastic devices which looked like small fax machines or modified telephones with little telescopic aerials. Fidorous said these were speed diallers. He went on to excitedly explain how the best of these machines was capable of dialling up to thirty phone numbers in a minute.

5. Cardboard flooring. A large sheet of cardboard laid out over some of the boxes creating a waist-high ‘flying deck’. From the thickness of the cardboard and the arrangement of the boxes it looked unlikely that this deck would be able to support anyone’s weight without collapsing.

6. Steering wheel. The steering wheel from a Volkswagen laid flat on the cardboard flooring.

7. Stepladders. A set of old wooden stepladders unopened and leant against the boxes as a completely impractical stairway up from the floor to the flying deck.

8. Strimmer. A green plastic garden strimmer laid against a box so the strimmer’s head and strimming wire faced out and away from the rest of the assemblage. Fidorous called the strimmer ‘Prop 1’.

9. Office chair. To the right of the strimmer arrangement, a slightly battered office swivel chair with blue padding. Like most office chairs, this one had wheels but these had been disabled with five or six bike chains, several padlocks and a steering wheel lock. A long garden cane lay across the seat.

10. Ian the cat. Asleep.

11. Coat hangers. Several dozen metal coat hangers arranged around the edges of the leading plank. The coat hangers had been connected together hook-to-corner or hook-to-hook to create a haphazard sort of chain.

12. Nobody’s laptop. Nobody’s laptop mounted on a plastic packing box. The laptop was on, the screen glowing blue and scrolling with heavy white source code. An internet cable ran from the back and away up into the rafters. A black power cable connected the laptop to the car battery in the tea chest.

13. Box of paper. A cardboard box positioned on the edge of the plank outline and filled with reams of blank A4 paper. A letterbox slit had been cut into the away-facing side of the box.

14. Desk fan. A big cream desk fan with a cage around the blades standing upright a few inches outside the plank outline. Fidorous referred to the desk fan as ‘Prop 2’.