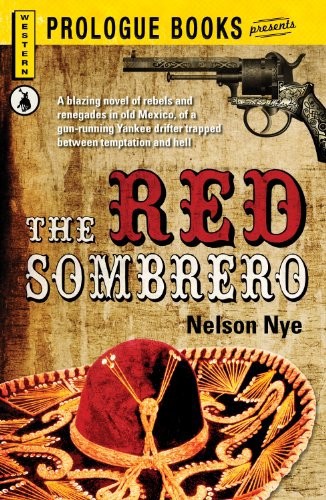

The Red Sombrero

SOMBRERO

A Crest Reprint by

a division of F+W Media, Inc.

T

HE SUNBURNED

, dust-streaked American in the cowman’s boots of soft, hand-tooled green leather groggily gripped the bar with an unsteady left hand and peered blearily around with red rimmed eyes in which a faint distaste marked the wreckage about him. The last things he could remember were Descardo’s foul mouthed cursing, the sound of the guns and the look of himself in the bullet splintered glass of the back bar-mirror.

He could not recall if this were El Cuervo, Tinajas de Canterrecio or Samalayuca — it could be San Ignacio even, he thought, listening to the noises made by Tano’s rebel army. Dust motes danced in the bright glare of sunlight coming through the shattered windows and he caught a burst of profane laughter, shivering as with a cold and trying to pull himself together.

At least the guns had quieted. The head men of this place had secured their ransoms and been turned loose, or there were a lot of extra hats in the plaza. ‘Liberator of the Downtrodden’ Sierra signed himself and perhaps, by his own lights, he was. Revolutions seemed to require continual outlays of cash, and cash was one thing Tano knew how to get quickly. “Lives are cheap. Good rifles cost money,” the American remembered him declaiming the one time he’d stuck out his jaw to remonstrate. “And blood, my friend, is something, once spilled, you can’t put back in your pocket.”

The American, who was built like a balding shop-clerk, remembered that. It was one of the reasons he gave himself for this guzzling. And quite on a par with the rest of his reasons, because he drank to forget that he had once been different — not a man perhaps of unusual ideals or of great moral courage, but a man at least whose background could never have countenanced the more lurid of the events which had fetched him to the point of being a bandit’s scorned advisor.

Since the town had been taken, a short while after dawn, he had emptied three bottles, not of gut rotting cactus brews but good stateside whisky, the like of which he’d not tasted in months. He’d put it down like a gentleman, from a glass and without hurry, a kind of toast to the past which could never be again.

And there was the folly of it — of any kind of drinking. The more you took aboard, the more you needed to keep the pictures blurred. Christ! Forty years old tomorrow! And what could he show for them beyond the sad knowledge that all you got out of a bottle was habit!

• • •

He heard boots in the doorway but he didn’t bother turning. Six months in the field with Tano Sierra had taught him to recognize Descardo’s step as far off as he could hear it.

There was no love lost between them. Though the American held a rank of lieutenant-colonel and was assistant chief of staff, Descardo, who was Tano’s right hand man and a general in his own right, used him like an errand boy and away from Sierra’s hearing invariably called him ‘that gringo jellybean.’ In his more knowledgeable moments the American considered Descardo a butcher who had picked up Death for a mistress — an opinion shared by others though not passed around in the open.

“Borracho!” barked Descardo. “All the time drunk as a no-account!”

The American looked around then, smiling as though he had been paid a great compliment. “I but do my best, General. With the Army of Liberation it is not always too easy to sustain the illusion of freedom.” He bowed, still grinning, and emptied his glass. “Is there some little thing I can do for you?”

“Bah!” growled Descardo in an explosion of oaths.

They were about of a size, those two, both undeniably handsome and both sporting mustaches but having very little in common beyond this. The general’s personality was fiercely aggressive. There was no excess flesh on his mesquite-tough frame and all his movements held the grace generally ascribed to a stalking tiger. His eyes were bleak as windswept ice. He still had on the black coat with red pipings he had worn in the dark of the attack this morning and the dust of battle had not yet been brushed from it. His features were angular and filled with vitality, not blurred like the American’s from continual infusions of alcohol. A strong face, Descardo’s, which the dark line of the greasy chin strap seemed to threaten to cut in two, even shaded as it was by the drooping brim of his great Chihuahua hat.

The Army of Liberation was more truly democratic in the matter of its dress than in any other observable particular. The majority of the men garbed themselves out of plunder whenever and wherever taken, the most repeated phenomenon being the crossed bandoleers and Chihuahua hats which many of Sierra’s officers also wore. But no one had a hat quite like Descardo’s. It was red. It was known up and down the whole immensity of the border and was worth more, Tano said, than a whole platoon of foot soldiers.

The American suddenly broke into song. Lifting his whisky tenor in an off-key rendition of

Jalisco

which, if somewhat erratic at least had the grace of being couched in faultless Spanish, he beat out the tempo against the bar with a bottle.

The general took a dim view of this performance which he appeared to feel in some manner underrated him. He glared, took a turn and glared again. “Silence!” he snarled, tugging out a massive timepiece which had formerly been the prized possession of Cipriano Valdez y Chalmancos, the late Mayor of Pilares. “Come!” he said, scowling into its face. “The Chief calls a conference. He will not like to be kept waiting.”

The prospect of another of Sierra’s conferences brought a lugubrious groan from the American. “Why not tell him you couldn’t find me?” he said, knowing from much experience no one else would be able to get in a word edgeways. “He don’t need any help laying out his strategy. Help yourself to a bottle and let’s just stay here and vegetate.”

“Do I look like a gringo jellybean?”

The American peered at him owlishly as though seriously considering but finally, as though forced to it, reluctantly shook his head.

The general’s face flamed. His brow got dark as a thundercloud but what could you say to a fool such as this? Anyone else he’d have shot long ago but he dared not shoot this one, and both of them knew it. It tickled Sierra’s vanity to have on his staff a Norte Americano who could twist words around to where nobody understood them.

“You will come now,” Descardo said harshly, “or I will see that you get no more whisky before this campaign is over!”

The American shrugged. Then, knowing it would further infuriate Descardo, he turned with a great show of leisure and, going behind the bar, picked up a fresh bottle before moving doorward. “Did the moguls pay up?”

“Of course. We had to shoot three of them,” Descardo said, scowling. He looked at the watch again. “Get yourself together and brush that filth off your clothes. In one hour and forty-three minutes the Chief is taking the solemn vows of matrimony — ”

“Not again!” the American groaned with mock horror, throwing his hands up.

Descardo did not grin. He said, “The Chief likes everything legal,” and kicked the broken panels of the door aside, stepping out, the American following, still trying to get the dork out of his bottle.

• • •

There was never much point in conferring with Sierra, for not only did he present all the problems; he mapped the strategy and made the decisions and rapped out his orders regardless of anything proposed by another. Advice ran off his back like water. He called these gatherings, in the American’s opinion, just to hear himself talk, and this present occasion appeared geared to the groove.

The Liberator’s temporary headquarters had been set up in a store whose air was pungent with the reek of sacked fertilizers, fish and the strings of red peppers that hung from the rafters. Blue-tailed flies swarmed over the edibles in clouds and their buzzing made a kind of not unnatural background to the contrast of Tano’s rhetoric.

There were mountains in the west and the apparent plan was to cross these and go into camp at Laguna Guzman, a pretty fair-sized lake about fifty miles south of the gringo border. Here, Tano said, they would spend two days to get the horses in shape. Then, having taken Boca Grande, they’d push through the northern pass to strike at Las Palomas.

All the colonels nodded. Descardo scratched his back against a crate of something marked

AGRICULTURAL IMPLEMENTS

and said, “Yes, my General,” flicking dust from a boot with the braided quirt that always hung from his left wrist.

Sierra’s coppery glance flashed up and around (he was the only one seated), coming back to the American’s face as he leaned forward. “Yes? And what do you say, Reno?”

The American, with the half-gone bottle still hanging from a hand, was propped against the doorframe, staring into the hot glare of dust off the plaza. With that scraggle of whiskers sticking out of his face, all the lines of it slack and loosened by the whisky he had downed without food since the battle, you might have imagined he was too crocked to know he had been spoken to.

He wasn’t. He hadn’t been able quite to reach that desired state since signing on with Tano — about the nearest he could achieve was a kind of lighter-than-air sensation, a sort of suspension, which granted his mind no really adequate relief from the tramp of his weary reflections.

He wasn’t seeing the dust or those shapes lying in it or the miniature whirlwinds revolving about them in the pitiless light which embalmed the dull plains with their clots of dead grass grayly shriveled in the heat. Once again he was eyeing the things he had come from through the unconscious distortions of pride and disgust. Tomorrow, pride was mouthing its hope, he’d swear off it; but he was remembering with disgust that he had sworn off before. This virtue had seldom lasted beyond the sight of the next dispensary.

He pulled his head around, grinning, scrubbing one hand across the scratch of his unshaved cheeks. His other hand brought up the bottle and shook it. “I say it’s time for another drink,” he hiccuped, wedging himself against the doorframe again. “Viva Sierra! And hell to the fools who can’t tell which side of their bread gets the butter.”

The lowering bottle went from hand to hand and when it was empty Sierra said, “And what do you think of my plans, friend?”

“I think they stink,” Reno told him, still with that foolish grin in his whiskers.

The place became still as a buried coffin.

Tano stared at him blankly. Then a dark tide of red crept up over his cheekbones and he jumped to his feet, the others stumbling back from him. With a single motion his hand got a pistol, pulled back the hammer and levelled its snout at the American’s head. “Now, say that again.”

“They stink,” Reno nodded, expression thoughtfully critical. “You’re going in the wrong direction, for one thing. All these victories you been having — what the hell good are they? No military significance.”

“No significance!” Tano shouted.

“That’s right. Bandit style. Kid stuff. You got to take a

big

town. Agua Prieta’s the place you should aim for.” He grinned like a man who held no hard feelings. “That’s what I would do.” He belched, said, “Your pardon.” Then: “You got another bottle around?”

The mouth of Sierra’s gun barrel was not three feet from the American’s face. Above the sights you could see the coppery glints of Tano’s eyes. These looked like golden veined pieces of agate. Reno stared at them as though he were too far gone in his cups to understand what he was doing. If he had not been so tanked up he must have noticed the scarce-breathing way the rest of them stood there, the sudden thin flash of Descardo’s teeth. This gringo jellybean was asking for it. Descardo’s glance moved to Sierra expectantly.

“And why would you do that?” Tano whispered.

“The way to build up an army is to take bigger towns,” the American lectured. “Believe me, General, nothing in this world succeeds like success. You take Agua Prieta, the governor of this state — old Tiburcio — gets excited. If, besides, you also take Nogales, everybody gets excited. The country boys will jump at the chance to serve under you. Maybe some of the blue bloods too will come over. First you have the cause, then you have the effect.”

He pushed himself away from the doorframe, grinning around the pistol at Tano. “Simple as gutting a slut,” he said, “but you have to make the cause before you can get the effect. If you go on from Nogales and take Hermosillo, all over the nation they’ll yell ‘Viva Sierra!’”

Tano’s eyes swiveled a look at Descardo. Letting his arm fall he said, “That’s not such a bad idea,” and nodded. With a faint rasp of leather the pistol slid into the pouch at his groin. “I will consider this suggestion after I have taken Boca Grande and Las Palomas.”

The American blinked. He felt cold and sick. Experience told him to keep his mouth shut but some belated recognition of a national instinct made him say almost desperately, “But, General — Las Palomas is too close to the border!”

Sierra looked at him coldly. “Nogales is closer.”

“But Nogales is a logical place for you to go. Las Palomas is eighty kilometers out of your way and there is nothing — ”

“There is a gringo mine and a good place for us to wait while you go to fetch the rifles I am buying from Luis Cordray. Enough! I have spoken. Tuerto — fetch the priest. It is time for the wedding.”