The Reluctant Film Art of Woody Allen (17 page)

Read The Reluctant Film Art of Woody Allen Online

Authors: Peter J. Bailey

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Performing Arts, #Film & Video, #History & Criticism, #Literary Criticism, #General, #Literary Collections, #American

But—as Frederick comments about Pearl’s reading of the off-Broadway play—“Well, it was a little more complex than that, don’t you think?”

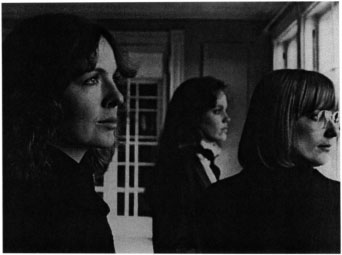

As numerous reviewers have noticed,

Interiors’

closing image of the three sisters gazing meditatively out the window at the ocean which took their mother’s life self-consciously reprises the famous image of Bibi Andresson and Liv Ullman used as publicity stills for Bergman’s

Persona

. The significance of this act of cinematic homage is complicated by the fact that Allen had reproduced the same image parodically toward the end of

Love and Death

.

28

“The water’s so calm,” Joey says as the window’s light bathes the three women’s faces. “Yes,” Renata agrees, “it’s very peaceful” (p. 175). This image undeniably approximates the films opening image, but with a highly significant difference: the five precisely spaced and perfectly framed vases evocative of Eve’s aesthetically ordered familial cosmos which is that initial image have been replaced by three flesh-and-blood human beings. This image affirms that in the aftermath of the violence which took their mother, the sea is now calm and peaceful. In other words, Eve’s self-sacrifice has been efficacious: there is sadness in the expressions of Joey, Flyn, and Renata, but there is an unprecedented resolution on their faces, too—one reflective, arguably, of their liberation from the art/life dichotomy their mother imposed upon them. For them this conflict seems to have been alleviated, but the Bergmanian saturation of the closing scene significantly problematizes the film’s resolution of this thematic conflict. In

Play It Again, Sam

, Allan Felix attempted to throw off the yoke of Bogart’s incapacitating influence on him by reenacting

Casablanca’s

most famous scene, his replication ironically reaffirming his thralldom. The ending of

Interiors

projects a similarly equivocal resolution. Whether Allen created this equivocal ending with the same purposefulness and deliberation is considerably less certain.

The plot of

Interiors

affirms the ascendancy of Pearls vital philistinism over Eve’s life-denying aestheticism but, as Pauline Kael pointed out, “After the life-affirming stepmother has come into the three daughters’ lives and their mother is gone, they still, at the end, close ranks in a frieze-like formation. Their life-negating mother has got them forever. ”

29

As Kael implies, it is the films style more than its plot which perpetuates Eve’s dedication to the redemptions of formal symmetry, and its difficult to separate the movie’s final image from the filmmaker who so obviously inspired it. In

Interiors

, Allen was clearly attempting to create the sort of “poetic” film he perceived Bergman as making. Commenting on the unsurpassable effectiveness of Bergman’s death metaphor in

The Seventh Seal,

Allen admitted that he’d “love to be able to transmit [his preoccupation with mortality] through poetry rather than through prose” as Bergman can. “On the screen one does poetry or one does prose….

Persona

and

The Seventh Seal

are poetry, whereas a John Huston film is usually prose, of a wonderful sort… But Bergman works with poetry so frequently I have to think… which of his films are not poetic. If there are any that are not. ”

30

Allen has proven himself no more successful at creating Bergmanesque cinematic poems than Eve is at subjecting reality to her aesthetic imperialism, and it may be the “vulgarian” Pearl in Allen which has dictated that, his best poeticizing efforts to the contrary, he has continued throughout his career doing prose on screen. For all the sustained influence of Bergmans plots on Allen’s films and their attempts—sometimes facilitated through the employment of Bergman’s primary cinematographer, Sven Nykvist—to imitate the absolute visual purity of films such as

Autumn Sonata

and

Fanny and Alexander,

Allen’s movies remain narratives, not poems. Rather than producing movies which dramatize the conclusion that so many of Bergman’s films reach—as Renata phrases the idea, “it’s hard to argue that in the face of death, life loses real meaning”—Allen’s films tend to dramatize instead Pearl’s interrogatory response to Renata: “It is?” (p. 151).

Interiors,

therefore, is an extended homage to Ingmar Bergman which betrays great unease about its own indebtedness even as it unflaggingly invokes him as a major inspiration for techniques of serious filmmaking. The retreat from existence into art, which Eve epitomizes, is very much inflected by Allen’s conception of Bergman, about whom he once commented, “All you ever heard of [Bergman] was how reclusive he was on his island, Faro.”

31

In

Interiors,

Allen was incapable of completely repudiating the orderly consolations of aesthetic form encapsulated by Eve, for to do so would be to renounce his aspirations to the creation of serious art and to forswear the professional ambition that Bergman’s artistic austerity epitomized for him. On the other hand, to repudiate Pearl would be to reject his own pop culture heritage and to contradict his fervently held idea of life’s superiority to art. Consequently, Allen ended up making in

Interiors

a thoroughly honest and deeply conflicted film dramatizing, through its dichotomy between content and form, his own irresolvable ambivalence about life and art.

7

In the Stardust of a Song

Stardust Memories

KLEINMAN: Believe in God? I can’t even make the leap of faith necessary to believe in my own existence.

JACK: That’s fine, that’s tricky—you keep making jokes until the moment when you have to face death.

—Shadows and Fog

Anyone who has heard a Woody Allen monologue or watched one of his films is familiar with Kleinman’s rhetorical strategy, the same one employed by Sandy Bates in telling Isobel “You can’t control life, it doesn’t wind up perfectly. Only—only art you can control. Art and masturbation. Two areas in which I am an absolute expert” (p. 335). The difference in

Shadows and Fog

is that Jack, the philosophy student Kleinman befriends in Felice’s brothel, challenges the maneuver so central to Allen’s comedy. In both Bates’s and Kleinman’s one-liners, the speaker avoids committing himself to a position on a significant question by deflecting attention from the issue to himself and his own human inadequacies; thus, these jokes epitomize Allen’s frequently invoked notion of comedy-as-evasion. “With comedy, you can buy yourself out of the problems of life and diffuse them,” Allen told Frank Rich of

Time Magazine,

“In tragedy, you must confront them, and it is painful, but I’m a real sucker for it.”

1

At the risk of reducing Allen’s complex filmmaking career to a binary opposition, I’m contending that Jack’s rebuke of Kleinman’s comedic tactic for avoiding grave issues represents a summary explanation for Allen’s evolu-tion from making his “early, funny movies” in which the protagonist was a primary butt of jokes to the creation of his most thanatophobic movie,

Stardust Memories

.

In the extended fantasia that closes out

Stardust Memories,

Sandy Bates imagines himself assassinated by a fan who tells him (in a chillingly exact anticipation of John Lennon’s murder three months after the film’s release), “You know you’re my hero” before shooting him. At the memorial service, his analyst eulogizes the fallen Bates as someone “who saw reality too clearly. Faulty denial mechanism. Failed to block out the terrible truths of existence.” (He failed, in other words, to produce one-liners capable of deflecting those truths.) “In the end his inability to push away the awful facts of being in the world rendered his life meaningless…. Sandy Bates suffered a depression common to many artists in middle age. In my latest paper for the

Psychoanalytic Journal,

I have named it Ozymandias Melancholia” (p. 370).

The analyst’s invocation of Shelley’s poetic incarnation of mutability (“‘My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:/ Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair’”

2

) wins the enthusiastic approval of his audience, their weirdly inappropriate applause for the analyst mocking the solemnity of his judgment, mediating the experience for the audience of Allen’s film by reminding us that we’re watching a projection of the narcissistic interior landscape of Sandy Bates.

3

The way in which this scene offers its content only to comically deflate it reflects how far Allen’s rhetorical sophistication as a screenwriter had developed beyond the easy self-parodying jokes that represent in microcosm the structures of the early films. The fact that those self-deprecatory one-liners remain staples of his films down through

Deconstructing Harry

and

Celebrity

suggests the very real ambivalence Allen feels about his responsibility as a filmmaker to confront viewers with “the terrible truths of existence” or to distract them from these through comedy, which he once characterized as a means of “constantly drugging your sensibility so you can get by with less pain.”

4

Years before producing

Manhattan Murder Mystery,

Allen addressed this issue from his side of the camera, explaining to Eric Lax his misgivings about undertaking that film project:

I’m torn because I think I could be very funny in a comedy mystery and it would be enormously entertaining in a totally escapist way for an audience. But I can’t bring myself to do that. This is part of my conflict. My conflict is between what I really am and what I really would like myself to be. I’m forever struggling to deepen myself and take a more profound path, but what comes easiest to me is light entertainment. I’m more comfortable with the shallower stuff…. I’m basically a shallow person.

5

The ambivalence Allen expresses here about the production of comic as op-posed to serious cinematic art has been one of the central preoccupations of his career, his debate with himself having manifested itself in two different forms early in his filmmaking work: in the scripting and production of

Interiors,

and, more self-consciously, in the creation of the film he considered his most aesthetically successful before

The Purple Rose of Cairo, Stardust Memories

.

“I don’t want to make funny movies anymore,” Sandy Bates complains in

Stardust Memories,

“They can’t force me to. I—you know, I don’t feel funny. I look around the world and all I see is human suffering” (p. 286). His preoc-cupation with humanity’s pain is visualized by the infamous Song My assassination photo which seems to decorate his apartment wall just as images exteriorizing interior states appear on the fourth wall screen throughout Tennessee Williams’

The Glass Menagerie

.

6

Allen’s own depressive tendencies notwithstanding, he has, quite properly, impatiendy rejected the imputation that Sandy Bates

is

himself and that his perceptions are unmediated versions of Allen’s values and feelings. Allen has indicated, among other differences, that he had himself never seriously considered ceasing to make comic films,

7

and that if he had as negative an attitude toward his own film audience as Bates seems to have, he is savvy enough not to dramatize the fact in a movie.

8

In addition, Allen often characterized Bates as a filmmaker on the verge of a nervous breakdown,

9

Allen’s own production of a film a year over the past two decades offering little evidence of a director who ever faced psychic collapse. As I suggested in the

Radio Days

chapter, however, Allen’s relationship to the protagonists he plays is nearly always a vexed conflation of fiction and autobiography; consequently, it seems self-evident that many of Bates’s conflicts are exaggerated versions of conflicts that Allen has experienced. What those who criticize Allen for Bates’s ideas and visions ignore is the divergence from cinematic realism

Stardust Memories

takes just before Bates heads off to the film festival being held in Connecticut in his honor.