Read The Reluctant Film Art of Woody Allen Online

Authors: Peter J. Bailey

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Performing Arts, #Film & Video, #History & Criticism, #Literary Criticism, #General, #Literary Collections, #American

The Reluctant Film Art of Woody Allen (44 page)

Lane and Laura have a friend whose mother is a psychiatrist; they listen to her talking with patients through a hole in the wall, and DJ joins them. Her eavesdropping allows her to tell her father all of the most intimate fantasies of one of the clients, Von (Julia Roberts), whom they encounter in Venice. Consequently, Joe is able to invoke Von’s private imagery as his own perceptions and thereby convince her that he is, as she puts it, her “true soulmate.” Their magical encounter—“This could be me talking,” Von responds to one of Joes supposedly self-revelatory monologues—is purely the product of DJ’s girlishly antic intervention and results in amusing moments in which Joe, to Von’s utter astonishment, parrots her most secret desires and fantasies back to her.

7

The joke goes sour for Joe only when Von decides that, having met the man of her dreams in Joe—“It’s not that he’s tall or handsome,” she tells her analyst, “but he’s magic“—she can now comfortably return to her husband, no longer tortured by her fantasy of the perfect man and perfect romance existing undiscovered for her out in the world.

8

“But that’s so neurotic,” is Joes response when she reveals she’s leaving him, an accusation Von will turn back against him in this film in which, as in

Annie Hall,

the romantic and neurotic are seldom perceived as being separable from each other.

And so romantically deflated Joe and Steffi attend a masked ball to-gether (her husband having conveniently fallen into a Paris fountain and caught cold) at which all of the guests come disguised as Groucho Marx. (In

Hannah and Her Sisters

, a Marx Brothers movie becomes Mickey Sachs’s

raison d’tre;

so giddily affirmative is the surface

of Everyone Says I Love You

that in the end of it everyone actually

becomes

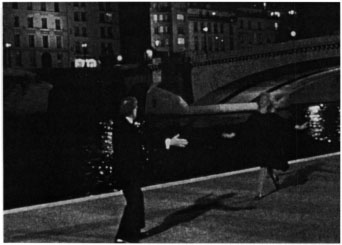

Groucho Marx.) After exchanging some diverting Groucho impressions at the ball, Steffi and Joe head off for a nostalgic visit to an old wooing site of theirs on the Seine. The riverside

pas de deux

which follows, facilitated by the use of a blue screen and invisible guy wires to make Goldie Hawn seem to fly her way through the dance, is one of Allen’s great set pieces, but for Denby it’s here that democracy-in-action once again mars the film. Whereas Hawn, in his view, dances creditably, Allen only “alludes to a man dancing, the way we all do in the living room, clowning for the children.” (As if “clowning for the children” in viewers weren’t what Astaire’s dances were always about.) Denby seems to assume that Allen’s attempt is to replace Astaire rather than, as seems more likely, mediating him.

In

Play It Again, Sam,

Bogart watches Allan Felix renounce his love for Linda, and then comments, “If I did that, there wouldn’t be a dry eye in the house.” The disparity between Bogart and Felix is the source of much of the humor in Allen’s script, the unapologetically moralistic conclusion of which is Felix’s realization that “The secret’s not being you … it’s being me. I’m short and ugly enough to make it on my own.”

9

The gap created in the film by the discrepancy between an idealized screen Bogart and an all-too-human Allan Felix comments satirically on both Felix, who can’t measure up to Bogart’s standards, and the Bogart image he tries to replicate, which is nothing more than a cultural fiction. “I-I-I just met a wonderful new man,” is how Cecilia, making the same point, describes her similarly screen-spawned beau, Tom Baxter. “He’s fictional, but you cant have everything.” Choosing, as Cecilia ultimately does, the “real world” over Hollywood fictions is the inevitable decision of Allen’s protagonists, even if, as Cecilia does, they inevitably return to the source of the rejected option to warm themselves in its glow.

The audience

of Everyone Says I Love You

is sufficiently conditioned by movie musicals to expect dance numbers to culminate in that glow, to have the same expectations of a romantic dance duet that Denby articulates. The female in such scenes is supposed to be supple, floating, airily feminine; Hawn largely fulfills her role, save for a moment when she seems to be getting propelled down the river perched on the side of a runaway safe, though even her performance totters on the brink of self-parody. The male is supposed to be effortlessly graceful, passionately engaged yet coolly urbane as he whirls, twirls, and dances his love. Joe makes an effort, but he’s too depressed at being “Thru with Love” to pull this off; he rises to the occasion only enough to give his despondency a touch of poignancy and to keep Steffi from sprawling on the quay. That Joe Berlin is not Fred Astaire, rather than being the flaw of the scene, is its point:

nobody

in Allen’s movies is Fred Astaire, and the implication is always there in his films that Fred Astaire wasn’t Fred Astaire, either. (In his era, reviewers often wondered whether Astaire wasn’t a little old to be playing romantic leads, too.)

Richard Schickels review of the film eloquently described its ambiva-lence toward its cinematic sources: all of the characters in

Everyone

want their lives “to be set to a score by Kern or Gershwin; they all want to believe that there is an authentic possibility of romance when they visit Paris or Venice; they all hope for the kind of transformative musical epiphanies that would suddenly be vouchsafed Kelly or Astaire as they soft-shoed through their happier—or anyway more stylized—realities.”

10

When they seek to sing out their desires, Schickel noted, they sound no better than most members of the audience would; when they try to dance their emotions, the effect is more evocative of Yeats’s “rag and bone shop of the heart” than of Astaire’s dancing cheek to cheek. Next to the Joe/Steffi number, Edward Norton’s winningly enthusiastic yet calculatedly clumsy soft-shoe performance of “My Baby Just Cares for Me” on the sales floor of Harry Winston Jewelers is probably the film’s classic dramatization of the difference between Hollywood musical epiphany and blundersome actuality; its visual poignancy is reinforced by the fact that we immediately learn that his baby, rather than caring just for him, is, like Cecilia, “a dreamer” fantasizing about a man who is “ideal, but then he isn’t real, and I’m a fool—but aren’t we all?” The film’s not completely celebratory answer to that question

is yes,

Skylar choosing an ex-convict her limousine liberal mother has been championing as the fully inappropriate object of her fantasy affections.

Von never quite figures out that her dream man, Joe, isn’t real, either—that he’s merely a cunningly prepped repository of her psychic life fraudulently regurgitated back to her, his “magic” quality projecting a thoroughly explicable illusion. Thus, if the film’s audience expects Joe to get transformed into some version of

their

dream man, they haven’t been paying attention to the movie’s demonstration of the falsity of dream man construction.

{Everyone Says I Love You

validates more precisely than any other Allen film Pauline Kael’s judgment that “Woody Allen’s parodies and fantasies are inseparable; their unstable union is his comic subject.”

11

)

The climactic dance scene never quite tips over into self-parody but (like the chorus’s closing dance in

Mighty Aphrodite,

also choreographed with mode-blurring equivocality by Graciela Daniele) remains delicately poised upon the point in our psychic geography at which our all-too-willing suspension of disbelief in the musical comedy felicities of Fred and Ginger confronts our knowledge of the world. The very real, fully-earned poignancy of the dance contends with its aura of being too much a reconstructed romantic movie scene, too much—and yet, given the dancers’ limitations, too little—of what our romance- conditioned hearts long to see.

12

What we are watching, after all, is not a romantically choreographed consummation of human love but a dance embodying human disconnection and disjunction, post-divorce’s poignant terpsichore. In their dance’s final movement, Joe prepares to pluck the flying Steffi from the air, but she soars over his arms and daintily touches down five yards beyond him, the moment symbolizing even better than the awkward dialogue between them which follows it the separation which Joe is no longer sure he ever wanted and which Steffi doesn’t completely regret. They agree that they’ve been better friends than they were husband and wife, a conclusion belied by their kiss, which obviously rejuvenates a more-than-friendly passion. Even Fred and Ginger would have had difficulty dancing the ambivalent emotions Steffi and Joe are feeling in this scene.

The nocturnal scene on the Seine cuts back to the brightly lit Groucho Marx ball, where, appropriately, the orchestra is playing “Everyone Says I Love You” from

Horse Feathers

and DJ has found someone new to say it to—the only person who came to the party dressed as Harpo. If Allen’s film seems inordinately bemused by the limitless capacity of youth to discover new crushes and recommence love relations, that’s just musical comedy compensation for all the minor key notes in the late-middle-agers’ narrative which suggest that, for them, time for new chance romance is running out—that it’s later than they think and that they have good reason to sing “I’m Thru with Love.” “Goodbye to spring, and all it’s meant to me,” the song’s lyrics, evoking the insuperable problem of time’s irreversibility, lament, “it can never bring the things that used to be.”

Joe’s daughter acts as if her father were incapable of attracting a woman unless he can reflect her most intensely private fantasies back to her, and when Joe tries to impress Von by emulating her jogging, he suffers an apparently unfeigned stress attack which suggests that his jokes about being old and out of shape aren’t just jokes. The only explanation for Steffi’s singing “I’m Thru with Love” at the end of the film is that the notion of love her kindly, devoted husband (Alan Alda) expressed in lines from Cole Porter’s “Looking at You” (“Looking at you, while troubles are fleeing and the sweet honey dew of well-being settles upon me”) is so familial, insular, and cozy as to practically eviscerate the word as the source of mystery and magic it’s often construed as being in Allen’s films. Grandpa’s senile belief that he can leave a message for his wife, dead twenty years, seems a commentary upon love’s capacity for delusion; his conviction that he’s going to a doubleheader at the Polo Grounds between the Cardinals and New York Giants (who departed the Bronx for San Francisco in 1957) seems to glance satirically at the kind of nostalgic reconstruction of the past so necessary to the good feelings of Allen’s movie. Similarly, Allen’s filmic idealizations of New York seem to be alluded to in a policeman’s explanation of where he’d encountered Grandpa: “We found him at Grand Central Station. He thought he was at the Botanical Gardens.” Grandpa’s rising from his casket at a funeral home to join his fellow dead in singing and dancing a rousing version of “Enjoy Yourself (It’s Later Than You Think)” is both delightfully funny and as frightening to contemplate as Allen claims it was for him when he first registered the song’s meaning as a child.

13

DJ’s equivocations regarding which of the seasons in New York is her favorite allows Di Palma wonderful opportunities to visualize the seasons as they pass, the film’s movement from spring through winter tacitly confirming the admonition of “Enjoy Yourself”: “The years go by, as quickly as a wink.” It’s a testament to the film’s spritely Tin Pan Alley soundtrack, its sumptuous photography, and DJ’s girlishly cheerful narrative which closes the film that

Everyone,

its significantly darker crosslights notwithstanding, could be read by one reviewer as “emotionally and artistically all but weightless, as ephemeral as a ditty dashed off on a bar napkin.”

14

No doubt many comedies, like happiness itself, can be expected to turn somber when scrutinized too closely. It’s clear from Allen’s few comments on the film that he was seeking to make “a very light picture—as they say, very broad.”

15

“I thought, I want to enjoy myself,” he told John Lahr. “I want to hear those songs from over the decades that I loved so much. I want to see those people on Fifth Avenue and Park Avenue. It comes from what I wish the world were really like.”

16

Those upbeat intentions are clearly borne out in the film’s numerous comic scenes: in the repetition of Skylar’s swallowing the engagement ring Holden gives to her; in an entire hospital floor’s patients’ and medical personnel’s song and dance rendition of “Makin’ Whoopee”; in Skylar’s ill-considered and ill-fated affair with ex-prisoner Charles Ferry (TimRoth); in the trick-or-treaters of DJ’s family’s building performing musical comedy standards for their candy; in the diagnosis of arterial blockage as the explanation for Scott (Lucas Haas) being a political conservative rather than a liberal Democrat like the rest of his family; and of course, in the funny, lovely songs which permeate the film.