The Reluctant Film Art of Woody Allen (30 page)

Read The Reluctant Film Art of Woody Allen Online

Authors: Peter J. Bailey

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Performing Arts, #Film & Video, #History & Criticism, #Literary Criticism, #General, #Literary Collections, #American

The final lines of dialogue of

Shadows and Fog

could provide an appro-priate—though thoroughly unnecessary—gloss for the point

The Purple Rose

of Cairo

makes about Depression Americas dependency upon Hollywood films, or, more broadly, about human beings addiction to fantasy. A circus roustabout hails the magic tricks of the Great Irmstedt (Kenneth Mars), “It’s true—everyone loves his illusions/’ his celebration eliciting a haughty revision from the magician himself: “

Loves

them! They

need

them … like they need the air.” Breathlessly, Cecilia watches Fred and Ginger performing a romantic

pas de deux

her life will never know, Monk, the Depression, and everything she’s learned about corruption on both sides of the silver screen all suspended in the epiphany which their dance and the lyrics Astaire sings conjures up:

Heaven, I’m in heaven,

And my heart beats so that I can hardly speak,

And I seem to find the happiness I seek,

When we’re out together dancing cheek to cheek.

For Cecilia, “choosing the real world” culminates in rededication to sav ing illusions of romantic harmony, to a belief in “dancing cheek to cheek”; for Allen, as for his protagonist, affirming faith in the artifice of cinematic resolution is similarly inevitable, since a world “with no point and no happy ending” is a world without meaning. Cecilia’s reversion to embracing the erotic union epiphanized by the choreography and lyrics of “Cheek to Cheek” is pure psychic necessity, because only these images of glamour, grace, and erotic concord can reconcile her to returning to her life with Monk and his irrationally affectionate and abusive behavior, his impotence before the ravages of the Depression, and his crap games exemplary of an ironically misplaced faith in chance. These images are the only happiness she knows how to seek; she needs them “like she needs the air” because without them, she would suffocate.

It is a testament to the film’s clarity of dramatic purpose that the ending of

The Purple Rose of Cairo

has inspired so little disagreement among Allen’s critics: the significance of Cecilia’s gradual, ultimately ecstatic reabsorption into a “heaven” whose utter fraudulence it has been her dismal necessity to confront throughout the film is a stunningly ambiguous effect lost on few who have written about the movie. For Christopher Ames,

Purple Rose

shows that “turning to movies for the satisfaction of desire poses the danger of increasing one’s alienation from the circumstances in which one lives,” while also demonstrating that “the escape offered by movies is magical, wonderful, and deserving of celebration…. Cecilia finds in film images that console and enrich her in a world that is fundamentally cruel and unfair.”

7

“Essentially,” Arnold Preussner agreed, “the silver screen environment contains no lasting value for its audience beyond that of temporary escape. Absorbed in great quantity, its effects may actually prove harmful. Remarkably, Allen manages to convey the radical shallowness of escapist comedy while simultaneously preserving audience identification with Cecilia, the ultimate fan of such comedy.”

8

If

Purple Rose

is Allen’s most compelling cinematic expression of his ambivalent feelings about the human dependency upon escapist illusions,

9

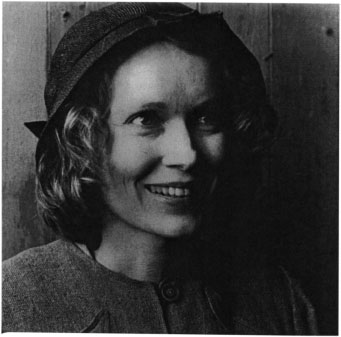

it is—as Preussner implies—in large part a product of Mia Farrows portrayal of the awestruck embracer of illusions. It is Farrow’s great achievement to make believable a character who seems to carry the Depression’s awesome weight in the drab wool coat and bonnet she wears but whose face is nonetheless capable of sudden ecstatic illumination when confronted with a movie character or Hollywood star; in Farrows bridging of Cecilia’s polar selves lies the success of

Purple Roses

dramatization of its central thematic antinomy. If Allen’s incapacity to elevate Mariel Hemingways beauty to Gershwinian magnificence in

Manhattan

limited that movies development of its structural contrast between idealistic projections of New York and human venality of its inhabitants, the central tension of

Purple Rose

is completely achieved through Farrows nuanced and completely persuasive portrayal of a hell-dweller’s des perate need to believe in heaven.

The remarkably lucid realism of

The Purple Rose of Cairo

with its alter-nation between Cecilia’s Depression reality and the black-and-white cham-pagne comedy world of Hollywood’s

Purple Rose

is truly Allen’s cinematic medium—his most characteristic films represent a convergence of the traditions of American theatrical naturalism and classic Hollywood film style. But Allen’s fondness for O’Neill, Tennessee Williams, and other naturalist dramatists and Hollywood realist filmmakers contends with his admiration for what he describes as the “poetic” cinema of Ingmar Bergman. “On the screen, one does poetry or one does prose,” Allen told Stig Bjorkman. John Huston’s films are “prose of a wonderful kind … But Bergman works with poetry.” In

The Seventh Seal,

Allen believes, Bergman created “the definitive dramatic metaphor” for death, and in his own efforts at creating poetic films, “I’ve never come up with a metaphor as good as his. I don’t think you can The closest I’ve come so far is

Shadows and Fog,

but it’s not as good a metaphor as his. Bergman’s is right on the nose. It’s great.”

10

Although Allen’s appropriation of German Expressionist film style filtered through

film noir

techniques for the purpose of making a Bergmanian “poetic” film was not well-received critically, the movie’s symbolic landscape and allegorical characters produce an intriguing modal reconceptualizing of the escapist fantasy/real life conflict underlying

The Purple Rose of Cairo

.

Shortly before his climactic assertion equating illusions with air in

Shad ows and Fog,

Irmstedt offers Max Kleinman, Allen’s character, a job in the circus as the magician’s assistant. Kleinman’s initial response maps the allegorical geography of

Shadows and Fog:

“I’m gonna join the circus? That’s crazy!” he objects. “I have to go back to town and, you know, join real life.” However, “real life,” as it is acted out in the unnamed European town created by Santo Loquasto’s atmospheric Kaufman Astoria Studio set for

Shadows and Fog

is best described by a

Rolling Stone

reporter’s characterization in

Annie Hall

of sex with Alvy Singer: it’s “a Kafkaesque experience.” The failure of the local police to capture the murderer terrorizing the town leads citizens to form vigilante groups, each of which has its own strategy for dealing with him.

At the beginning of the film, Kleinman is awakened in the middle of the night by one such group and coerced into joining their plan, though he is never told what the plan is or what role he’s supposed to play in it. As a result, he spends the entire night wandering around the fog-enshrouded town in search of instructions, failing utterly to understand why a “socially undesirable” Jewish couple has been arrested in connection with murders obviously committed by a single man, why his name appears on a list being compiled by the local priest and a police captain, or why citizens are being murdered by members of factions favoring different solutions to the bane of the homicidal maniac.

11

When Cecilia is obliged to choose between Tom and Gil, one of the screen-bound actors of

The Purple Rose of Cairo

comments that “The most human of all attributes is your ability to choose” (p. 456); “Are you with us or against us?” the leader of one faction threateningly interrogates Kleinman, who, once again invoking Kafka’s Joseph K, responds, “How can I choose? I don’t know enough to know what faction I’m in.”

12

Unimpressed by ignorance as an explanation, the faction leader berates him again, “Lives are at stake; you

have to make a choice!

”

The existential necessity to choose among unintelligible, indistinguishable options is the Kafkaesque fate of Kleinman, a self-identified “ink-stained wretch” who “doesn’t know enough to be incompetent”; it’s his insistence upon adhering to the ideal of human rationality which prevents him from falling in step with his rabid fellow citizens. “Everybody has a plan,” he tells Irmy, “I’m the only one who doesn’t know what he’s doing.” (Kleinman’s fel low townsman’s scheme—“Let’s kill [Kleinman] before he gives us all away”—reflects how perilous not knowing what he’s doing can be in this world of plans which replicate the scourge they seek to eliminate.) Unwilling to embrace some fragmentary truth as totalizing explanation—and thus refusing, in the terms of Sherwood Anderson’s

Winesburg, Ohio,

to become the “grotesque” that each of his fellow citizens has transformed himself into—Kleinman champions reason: when a mob accuses him of the murders, he responds, “This is a joke. Listen, we’re all reasonable, reasonable, you know, rational people.” The film’s immediate commentary on Kleinman’s assertion is to cut to Spiro (Charles Cragin), a psychic who sniffs out crime and criminals tele- pathically and has employed his faculty to smell an incriminating glass in Kleinman’s pocket: “Once again I thank the Lord,” Spiro prays, “for the special gift He has seen fit to bestow upon me.” Rationality doesn’t count for anything in this world under the imminent threat of death; none of the numerous questions of human ultimacy raised during this night—including the interrogation of the Doctor (Donald Pleasence) regarding the nature of human evil as it is manifested in the murderer—elicit even remotely adequate answers. (The characters’ attempts to solve ontological mysteries in

Shadows and Fog

—“So many questions!” the killer harrumphs dismissively before stran gling the Doctor with piano wire—are no more effective than Tom Baxter’s efforts at philosophical reflection in

The Purple Rose of Cairo,

speculations confounded by his inability to understand that Irving Sachs and R.H. Levine,

The Purple Rose of Cairo’s

screenwriters, aren’t God.) Kleinman is the only citizen courageous enough to admit that he’s incapable of choosing because “I’ve been wandering around in the fog”—the fog which is the film’s externalization of the limit imposed upon human understanding by the presence of death, its benighting effects exacerbated by plans devised by humanity in futile efforts to clarify and illuminate their desperate existential circumstance. The alternative, then, is shadows.

If the town of

Shadows and Fog

is a projection of reality filtered through

The Trial

and parables of the lonely Kafka sojourner whose experience consists largely in being disabused of his conviction that the institutions of the world are rational and just, the circus as an allegorical embodiment of the realm of fantasy and art is an even more Kafka-influenced reality. “When I see him out there in his makeup,” Irmy tells the prostitutes who befriend her of her lover, Paul, a clown in the circus, “just getting knocked around and falling in a big tub of water with all the people laughing, I can only think, ‘he must have suffered so to act like that.’” Painters, poets, novelists, and musicians are understood to create their art through the aesthetic transfiguration of their personal suffering, but a circus clown? Paul the clown, Irmy the sword swal- lower, and Irmstedt the magician are artists in the same sense that Kafka’s hunger artist is an artist, their “arts,” like his fasting, providing a model of how art works, helping to clarify what function it serves for those dependent upon its performance. “We’re not like other people,” Paul tells Irmy early in the film, “we’re artists. With great talent comes responsibility…. I have a rare opportunity now. To make people laugh. To make them forget their sad lives.” This is the affective justification of art Allen offers in

The Purple Rose of Cairo,

but whereas Hollywood’s glowing images in that film have the potency to win back Cecilia’s devotion despite all she’s learned of the duplicity and fraudulence existing on both sides of the screen, Paul’s art, for all his self-congratulation, isn’t working: “I’m an artist. Every town I’ve played in, I get huge laughs, and here, nothing. I mean, no one comes, and the few that do sit there stone- faced. Believe me, nothing is more terrifying than trying to make people laugh and failing.” Paul’s art (like Irmy’s and, subsequently, Irmstedt’s) is failing at the circus for the same reason that Kleinman’s appeals to rationality are persuading none of the vicious factioneers in the town: the presence of the murderer.

13

Allen initially sketched out the Kleinman plot of

Shadows and Fog

in “Death (A Play),” the one-act’s one-liner gravitational pull and its want of the film’s controlling metaphors of fog and shadows making it a substantially less resonant work, but one whose greater spareness frames its allegorical intent more distinctly. Stabbed fatally by the maniac in the play, Kleinman is asked by John, who finds him bleeding to death, for a description of the murderer. Kleinman’s response is that the murderer looks like himself. Once Kleinman has died, John proclaims, “Sooner or later he’ll get all of us.”

14

Death, incarnated by the killer whose various names—maniac, strangler, beast, evil one, murderer—suggest a spectrum of mortality and its causes, is the ultimate power in both “Death (A Play)” and

Shadows and Fog:

it dictates most of the characters’ actions in both play and film, inspiring fear, despair, philosophical speculation, and even Paul’s determination to abandon his circus art in favor of beginning a family. Ultimately, “Death (A Play)” has little original to say about death: its omnipotent and personalized, each person confronting her/himself in facing it.

Shadows and Fog

concentrates, instead, on human responses to the inevitability of death, expanding the civic confusion and brutality (“Soon we’re going to do his killing for him,” the

Shadows and Fog

Kleinman accurately predicts) that results from competing strategies for dealing with the murderer’s presence in town and the presence of the reality of death. “Nobody’s sure of anything! Nobody knows anything!” Kleinman summarizes the theme in the play, “This is some plan! We’re dropping like flies!” (p. 75). The film adds to the play’s allegorizing of death the competing circus allegory with its emblematization of art as temporary antidote to, then compensation for, human mortality.

15