The Rescue Artist (15 page)

Authors: Edward Dolnick

Tags: #Art thefts, #Fiction, #Art, #Murder, #Art thefts - Investigation - Norway, #Norway, #Modern, #Munch, #General, #True Crime, #History, #Contemporary (1945-), #Organized Crime, #Investigation, #Edvard, #Art thefts - Investigation, #Law, #Theft from museums, #Individual Artists, #Theft from museums - Norway

Pablo Picasso,

Boy with a Pipe

, 1905 oil on canvas, 81.3 × 100 cm

© Collection of Mr. and Mrs. John Hay Whitney, New York /Bridgeman Art Library /ARS

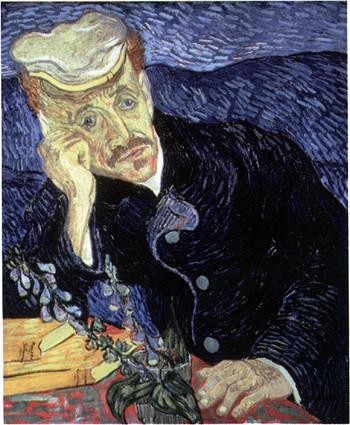

Vincent van Gogh,

Portrait of Dr

.

Gachet

, 1890

oil on canvas, 56 × 67 cm

© Private Collection /Bridgeman Art Library /ARS

Sid was glaringly out of place in a five-star hotel. Hill admitted to himself that he and Walker should have been more careful. Walker obviously wasn’t a Norwegian, and, much more important, he looked more like an armed robber than an international businessman.

Still, the close call left Hill closer to exultant than chagrined. He lived for such tightrope-without-a-net moments. “You can’t waver,” he’d learned in previous undercover ventures. “If you take time to gulp, you’re screwed. You’ve got to be as calm and relaxed and nonchalant and in control as you can be. You don’t run through your options. I don’t, anyway. I just trust my instincts. I don’t have a rational mind, and it’s so much easier to trust your instincts than it is to do a calculation. Usually it works out. Sometimes you get it wrong.”

This time it worked. Over the course of a few drinks, Johnsen’s suspicion of Walker gave way to something almost like camaraderie. The Norwegian leg-breaker recognized in the bad-tempered English crook a brother in arms. They were both professionals; they could work together.

The rooftop bar was more a drinking spot for tourists than for locals, because the prices were as stunning as the view. For Hill, flaunting his credit cards from the Getty, money was no object. Ulving and Johnsen were suitably impressed.

Hill kept the drinks coming and the talk flowing. The conversation dipped and meandered; there was no real agenda except to convince Ulving and Johnsen that they were indeed dealing with the Getty’s man. Each of the Norwegians posed a different challenge. Hill figured he had Ulving’s measure. The art dealer was unsavory and full of shit, but his self-importance made him vulnerable. Hill would have to watch his step when he talked about art, but he had enormous faith in his “bullshit art-speak mode.” And Ulving liked to go on about his helicopter and his hotel and all the rest, but Roberts was the big-spending, free-wheeling Man from the Getty, so Hill figured he had that angle covered, too.

Johnsen posed a graver threat. He was a switched-on, alert crook, not much on charm but canny and cunning. The story about Johnsen buying and collecting art was crap, Hill felt certain. When Hill launched into art bullshit, Johnsen didn’t have a clue. But he was dangerous anyway. With assholes like him, it wasn’t a matter of what they knew. Instinct, not knowledge, was vital. Crooks like Johnsen operated on intuition and experience. Are you the real McCoy or not? Am I dealing with an easy mark?

The worst thing Hill could do was give Johnsen the impression he could take his money

and

keep the painting.

At the bar with Ulving, Johnsen, and Walker, Hill held forth on the strange life and career of James Ensor. He was a Belgian painter, a contemporary of Munch, an odd duck who went in for a kind of Dada-esque surrealism. The Getty owned Ensor’s masterpiece,

Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889

. That huge painting, painted five years earlier than

The Scream

, had thematic and psychological tie-ins with Munch’s most acclaimed painting, “and what we have in mind is to show the great icon of expressionism and angst in juxtaposition with the great work of expressionism that relates to it in the Getty’s collection.”

Hill finished up with a few impassioned words about how important and groundbreaking the proposed exhibition would be. Johnsen seemed to have bought Hill’s line, or perhaps he had simply sat through as much art chat as he could take.

“Can we do the deal tomorrow morning?” Johnsen asked.

“Yeah, fine,” Hill said. “We can do that.” He ignored Walker—Walker was a bodyguard, not a partner, and didn’t need to be consulted on arrangements—and directed his attention toward Johnsen and Ulving.

“We’ll meet in the hotel restaurant tomorrow, for breakfast,” Hill said.

Hill strolled to the elevator and pushed the button for 16. He whistled a few cheery bars of an unidentifiable tune—for good reason, he had never tried to impersonate a musician—and headed to his room to see what the minibar might have in store. The next day’s plan, he felt sure, would go off without a hitch. It didn’t.

MAY 6, 1994

O

n his way to the rooftop bar, Hill had noticed that the hotel lobby seemed crowded, but he hadn’t paid much attention. In the morning he learned his mistake.

While he and Walker had been drinking with Ulving and Johnsen, hundreds of new arrivals had checked in. They had not made it to the pricey top-floor bar, but when Hill walked into the hotel restaurant the next morning, he could barely squeeze through the crowd. Who were all these characters greeting one another like old pals?

Hill would have been less puzzled if he had noticed the small sign near the registration desk: “Welcome to the Scandinavian Narcotics Officers Annual Convention.”

The hotel and the restaurant were crawling with plainclothes cops wearing badges that announced their name and rank. There were police and customs officers from Sweden, Norway, Finland, and Denmark, gathered in clusters around every corner and at every table. Every cop in Scandinavia, it looked like, and, along with them, wives, girlfriends, boyfriends, the works. On top of that, the Norwegian police had apparently decided on their own that they needed to protect Hill and Walker, and the entire top-of-the-range surveillance team was there as well.

The timing was terrible. Hill needed Ulving and Johnsen relaxed and ready to deal. Would they overlook the presence of 200 cops who had popped up in the middle of the first negotiating sessions?

A worse danger still—bad enough that Hill would have to exert all his will to resist the temptation to scan the room for familiar faces—was that one of those cops might be an old friend. Over the years Hill had worked plenty of drug cases and sat through countless meetings with police and detectives from all over Europe. What if some delighted cop came running over to pound his buddy from Scotland Yard on the back?

For the time being, Hill had only Ulving to deal with. Johnsen had announced the night before that he would skip breakfast and join the others later. Hill and Ulving checked out the breakfast buffet. Cops everywhere! Ulving seemed not to mind. Could he really be the honest outsider he claimed to be?

To Hill’s dismay, he spotted a high-ranking Swedish police official, a good friend. His name was Christer Fogelberg, and his expertise was in money-laundering scams. Hill had worked similar cases. Fogelberg had even modeled his unit on the corresponding one at Scotland Yard. He would be thrilled to bump into his buddy.

“Shit!” Hill thought. “He’s brought the whole entourage.” Fogelberg was on the other side of the restaurant, with his wife and his flunkies. “Do you mind if I sit on that side of the table, if we swap round?” Hill asked Ulving. “The sun’s in my eyes and I can’t see you properly.”

Hill scuttled round the table and sat down with his back to Fogelberg. Now he needed to finish breakfast quickly, so that he could be gone before Fogelberg passed by his table.

Oblivious to Hill’s suffering, Ulving twittered on, chattering about his business and his views on art. Occasionally he interrupted himself to take a few bites of breakfast. More chat. Now Ulving began contemplating a second trip to the buffet.

Hill, a much larger man than Ulving and normally a big eater, muttered something about getting underway. Finally Ulving finished his meal. Fogelberg still wasn’t done. Hill kept his back to Fogelberg and escaped out the restaurant door.

Safely out of sight, Hill made an excuse to Ulving about needing something from his room, and raced away. Then he phoned John Butler, the head of the Art Squad, in his makeshift office in his hotel room.

Hill told Butler to get a message to Fogelberg. Butler phoned Stockholm police headquarters, who delivered the message that there was a major undercover operation going on. If Fogelberg recognized anyone, he was to do nothing about it. Hill, who had no idea how long it would take to get the message through, continued to skulk around the hotel.

Hill’s only “plan” in case Fogelberg

had

spotted him, he admitted to Butler, was to cross that bridge—to jump off it, really—when he came to it. “I would have come up with

something

. ‘You’ve got the wrong guy,’ I don’t know, I’d turn on my American accent, I’d think of something. The best plan was to hide, which is what I did.”

The escape left Hill almost giddy. He was at least as fond as the next person of telling stories that did him credit, but the stories he liked best were ones where there was nothing to do but duck your head and trust to fate. In Hill’s world, a plan that worked was satisfying, but a stroke of undeserved good fortune was thrilling. Hill would have happily taken as his motto Winston Churchill’s remark that nothing in life is as exhilarating as being shot at and missed.

Having alerted Butler, Hill hurried back downstairs and met Ulving in the coffee bar. By this time Johnsen had showed up. During the discussions the night before both sides had agreed on a price for

The Scream’s

return: £350,000, the equivalent of $530,000 or KR 3.5 million. (Why the price had fallen from the £500,000 Ulving had mentioned earlier, Hill never learned.)

Walker had already converted the money from British pounds into Norwegian kroner. The fortune in cash was in the hotel safe near the reception desk, still in Walker’s sports bag. Hill feared he might trip up during the money talk, blurting out something about “pounds” that would mark him as English, when, as Chris Roberts, he should have been thinking in dollars. To keep from screwing things up, he steered clear of “pounds”

and

“dollars” and stuck with “kroner.”

Even tiny decisions like that could be crucial. Over the years, Hill had wrestled with the questions that lying brought with it—how to justify it, and when to do it, and how best to get away with it. On his bookshelves at home he had made a place for such tomes as Sissela Bok’s

Lying: Moral

Choice in Public and Private Life

, but his own approach leaned more toward the practical than the philosophical. “Remember,” he would say, in the earnest tone of a Boy Scout leader teaching his young charges about wilderness survival, “lies are valuable—you don’t want to go around squandering them. You want to concentrate them, and you have to be effective with them.”

Occasionally Hill would try to explain to non-police friends the gamesmanship at the heart of undercover work. One essential lesson: when you lie, lie big. “The

whole thing

is a lie,” Hill would explain. “You’re a cop on a cop’s salary and you’re posing as someone who travels first-class and has half a million pounds in his suitcase. That’s okay. What gets you in trouble is lying about the little things; that’s when things get hard to remember and when you trip yourself up.

“If you try to remember too much, then you won’t act naturally. You always want to tell the truth as much as you can possibly do. It’s easier, there’s no conscience involved, there’s no blushing—you’re just telling the truth, so there’s no problem. That’s part of it. The other part is that you need to convince the villains that you’re a real person with a real life, and that’s easier to do if you can talk more or less freely.”

So Hill said. His practice contradicted his theory. In real life, as with the Getty plan, Hill rarely went for simple efficiency if he could come up with something elaborate and dangerous instead. Near the end of

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

, Tom Sawyer devises a complicated scheme to rescue Jim, the slave who has run away with Huck Finn and been recaptured. Huck had proposed a straightforward solution. “Wouldn’t that plan work?” he asks.

“Work? Why, cert’nly it would work,…” Tom says. “But it’s too blame’ simple; there ain’t nothing

to

it. What’s the good of a plan that ain’t no more trouble than that?”

Then Tom unveiled his own plan. “I see in a minute it was worth fifteen of mine for style,” Huck says, “and would make Jim just as free a man as mine would, and maybe get us all killed besides.”

Huck at once rejects his own plan in favor of Tom’s. Charley Hill would immediately and instinctively have cast the same vote.

It was midday on Friday, May 6, and the coffee bar in the Plaza was quiet. Hill’s bodyguard, Sid Walker, leaned back in his chair and glared at the world. Walker’s main assignment was to look menacing. He was up to the task. Hill’s role was to do the talking. They were performing for an audience of two, but they had to get it right. If all went well, the two performances would complement one another—Hill’s improvised blather about art and the Getty was a soothing melody line; Walker’s nearly silent menace served as an almost subliminal growl, a bass line that reinforced the notion that these were indeed men accustomed to making clandestine deals.

The time was right, Hill judged, to snare Johnsen once and for all. “Sid, you want to show him the money?” “Yeah, sure.”

The etiquette here was more delicate than an outsider might have guessed. “Please” would have been a faux pas. Chris Roberts would use the word “please” for waiters and the like, to show that he was a gentleman, but he had to make sure that no macho crook took him for a wimp. If thugs sensed weakness, they’d move in. Hill was unarmed, in enemy territory. This was no time to play the ingenue.

Walker, too, had to watch himself. His job was to look after Roberts and his money. But he was playing a crook, not a servant. Any kind of “yes, boss” byplay would have been out of place, a jarring intrusion of Jack Benny and Rochester into a world where they didn’t belong.

The tiny issue of saying “please” or skipping it hinted at a far larger issue. The challenge for Hill, in playing Chris Roberts, was that he had to send two messages at once, and they contradicted each other. He had to convince the crooks they were dealing with a genuine member of the art establishment and at the same time he had to come across as a man of the world who couldn’t be pushed around.

Walker and Johnsen headed off toward the reception desk to look at the money. The scene played out almost wordlessly, punctuated only by a series of barely audible sounds. Footsteps on the gleaming floor, as Walker and Johnsen crossed the lobby. The click of the door to the hotel safe. Johnsen craned his neck, trying to peek around Walker’s broad back.

Walker turned toward Johnsen and held out the bag. A quiet

zzziiipp

as he opened it. Johnsen gawked.

Three and a half million kroner.

“You want to count it?”

No, said Johnsen, he didn’t need to bother counting. The money rustled softly as Walker flicked at a stack of bills with a thick thumb. Walker locked the bag back in the safe.

Johnsen came back to the table unable to hide his excitement. Hill was jubilant. Johnsen had seen the money, and it had gone to his head. “Hooked him!” Hill thought.

Hill and Walker had known all along they had the right bait. The trick was to dangle it gently rather than to risk scaring the crooks away with too much splashing and drama. The image to convey was that this was just one more step in an ongoing business negotiation. No fanfare, no big talk, no urgency.

Hill had learned in earlier deals how fraught this moment was. You had to keep the tone casual: “Do you want to have a look at the money?” But it’s not casual, it’s

crucial

, because now you’ve captured their imagination. Now they know that all they’ve got to do is deliver on their end of the bargain, and all that money will belong to them. Sometimes they count it, sometimes they don’t, but that’s not the point. The point is for them to know the money is there. Talking about it is one thing. Seeing it is something different.

Johnsen tried to play it cool but couldn’t quite carry it off. Ordinarily he left most of the talking to his art dealer pal, Ulving. Today, as always, Ulving was chattering away. But now, revved up by the sight of a bag bursting with cash that was

this close

to belonging to him, Johnsen joined in.

Then he stopped dead, interrupting himself in midsentence. Ulving, oblivious, kept whittering on. Johnsen stood up and walked over to a man sitting at the bar.

Johnsen stood behind the stranger for a moment and then rapped him hard on the back, as if he were knocking on a door. The hollow sounds echoed. “What are you doing with a bullet-proof vest?” Johnsen snarled.

The man shrank into his seat and stammered something incoherent. The vest was borrowed; someone had asked him to test it; he’d been thinking of buying one. Johnsen cut the floundering short. “You keep staring at us over that newspaper. And you ordered your drink half an hour ago, and your glass is still full.” He gestured at the man’s untouched beer. “What’s your game?” No reply.

Johnsen stomped back across the room and flung himself into a chair. “The guy’s a cop.”

“Shit! Now what?” Hill thought.

How to explain away a plainclothes cop doing his (clumsy) best to keep tabs on Johnsen and Ulving? And if the Norwegian police had decided that Scotland Yard needed their help with surveillance, why hadn’t they told Hill and Walker what they were up to?

Hill hadn’t planned for this, and he had nothing ready. Something popped into his head. “Well, shit,” he grumbled, “A few months back they signed the Arab-Israeli peace accords here. They must be worried about some kind of terrorist attack. I guess they’ve got these guys looking after all the goddamned cops and the other people here for this horseshit conference.”

Hill was referring to the Oslo accords, which had been brokered in large part by Norway and signed by Yitzhak Rabin and Yasser Arafat in the fall of 1993. Hill had followed the negotiations closely. Back in London, Hill sometimes sat at his desk with a cup of coffee and a newspaper, and his fellow cops liked to tease the Professor for reading the

Times

when he could have been checking out the topless girl of the day in the tabloids.

Hill’s tone, as he griped about the surveillance cops in the hotel, was nearly as important as the message. He had to sound impatient, irritated, bored with the great “discovery” that Johnsen was so excited about. Anything but flustered, even though Hill had grabbed at the business about terrorists the way someone headed over a waterfall would grab at a tree branch over the water.