The Riddle of the River (3 page)

Read The Riddle of the River Online

Authors: Catherine Shaw

‘That’s the woman who bought the bracelet!’ she said at once. ‘But – how strange she looks! What is this picture? Is she sleeping? She looks as if she were dead!’

I felt the taut, narrow possibility of imminent success stretching before me, so fragile, so easily snapped.

‘She is dead,’ I said. ‘Her body was found floating in the Cam, and the bracelet was on her wrist.’

‘Oooh,’ she breathed, staring at me. ‘Was she killed?’

‘It seems she might have been,’ I admitted.

‘Are you from the police?’

‘No,’ I said quickly. Nothing causes witnesses to close up like clams so much as the mention of that hard-working, earnest and deserving body. ‘I’m just a friend,’ I continued, both vaguely and untruthfully. ‘I thought that I recognised her bracelet as coming from here, and offered my help in trying to identify her. You see, the body is completely unidentified. Nobody has any idea who she is.’

‘Oh,’ she breathed thoughtfully. ‘And the gentleman that I saw – is he the

murderer

?’

‘Very likely not,’ I said. ‘It would be a bit too dangerous for him to have done it, wouldn’t it, after all kinds of people like you had seen them together?’

‘Well, but he might be,’ she insisted. ‘That kind of gentleman wouldn’t think anything of being seen by people like me. People like me don’t even exist for him.’ She gave an impatient little gesture of frustration.

‘Well, that’s as may be,’ I said. ‘People do tend to take more care if they are about to commit a murder. I don’t know, but I do think that if we can find the gentleman you saw, he will at least be able to tell us her name, and that is all I want right now.’

‘Oh,’ she said. ‘Well, if that’s all, I could just run out and ask him about it, next time he passes.’

‘No!’ I said quickly. ‘Don’t speak to him – I definitely advise you not to speak to him at all if you see him, least of all about the young woman or the bracelet.’

She gave me a quick, penetrating glance. ‘So you do think…’ she murmured.

‘I don’t really, but of course we must remain on the safe

side,’ I said firmly. ‘We don’t know, that’s all there is to it. It would be best if he were not even to lay eyes on you. What I would like to ask you to do, next time you see him passing, is to follow him a little way and see where he goes. Then send me a message at once.’

‘But I’m not supposed to leave my post,’ she hesitated.

I looked around. To the left of the exotic items was a stand selling silk scarves, and to the right several handbags were on display. There was a young woman behind each of them, and neither of them was doing anything.

‘Well,’ she admitted, following my glance, ‘I could run out for just a few minutes if I see him again.’

‘How often do you think you see him?’

‘It’s hard to tell. But fairly often, I think. Every few days, maybe? Though I don’t believe I’ve seen him since the Chinese sale.’

‘If you see him, have a note sent to me immediately,’ I told her, writing down my name and address on a piece of paper which I handed her together with a modest financial encouragement. She flushed.

‘I can’t take this,’ she said.

‘This is a job I am asking you to do for me,’ I said. ‘It is work, honest work. It is quite all right. In fact, it is very important – you do realise that? A girl hardly older than yourself has died. We must find out who she was and how she died.’

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘I do see that. Even if she was just a…even if, well, what I mean is, whoever she was, she was enjoying her life and didn’t deserve to die. I see what you mean. Even if she is dead, this is still like giving her a helping hand. I’ll do it.’

Our eyes met across the counter, scattered with its litter of objects, delicate, frivolous, artistic objects, all made uniquely for pleasure – the pleasure of young girls. Her eyes like deep pools showed me anxiety, concern, a consciousness of suffering, a search for meaning.

‘She shouldn’t have died,’ she said again, thoughtfully. ‘She was happy.’

‘That’s an interesting remark,’ I said. ‘Do you think she was in love with the gentleman?’

‘Him? Oh, no. That was just – well, professional. She was very nice to him. He was a gentleman friend. And she liked the bracelet. No, she was just happy in general, I think, happy and excited. Maybe a little too excited. Maybe almost nervous. I can’t remember exactly.’

An unwed girl, ‘professionally’ befriending an elderly gentleman, a baby on the way…and yet the impression she gave – to another girl of her own age, no less – was of being happy. Why happy? Would not a girl in such a situation be rather fearful and troubled, if not in despair? Yet she seemed happy. And days later, she was dead.

‘Vanessa – you’re waiting again,’ said Arthur, after dinner had been cleared away and the twins sent upstairs to be put to bed.

‘Who, me?’ I said, dropping a ball of wool which I had taken out of my workbasket and put back twice already.

‘Yes, you. Listen, nothing is easier to observe than a waiting Vanessa. You fidget and don’t do anything.’ Rising, he came to lean over me and smiled.

‘I won’t ask you what you’re waiting for, but I will ask you if you’ll have to wait long.’

‘I don’t know, that’s the trouble. It could be days and days. Oh, Arthur, you’re right, I do hate waiting and not being able to do anything. It’s my worst defect, I know. I really ought to cultivate the Eastern art of patience.’

‘Well then,’ he said, ‘since you haven’t done that yet, let me suggest instead that you relieve the anxiety by spending the weekend in London with me. You know Ernest Dixon and his wife have been inviting us for ages – they have an extra room in their flat. He’s just written to me about it again, and he even asked what we’d like to see. Do let’s go, it would do you good.’

‘Oh, I would love to,’ I said eagerly, thinking secretly that Robert Sayle’s is closed on Sundays anyway. ‘But how can I leave the children for a whole weekend?’

‘Stuff,’ he said. ‘Sarah will spoil them rotten and they’ll simply love it. And we’ll come home on Sunday. We’ll spend just one night away.’

‘But what if the message I’m waiting for comes while I’m gone?’ I worried. ‘I don’t expect it so soon, and yet that is just what

would

happen, isn’t it?’

‘Well, there I can’t give you any advice, as I don’t know what kind of message you’re waiting for. Once it comes, what need you do?’

‘Well, that will depend on what it says,’ I admitted, wondering what the shopgirl – whose name I suddenly realised I had stupidly omitted to ask – could possibly write, even if she did spot the familiar gentleman.

Come at once

–

he’s in the tea-shop?

Or better,

Have managed to talk to him and found out his name?

No, no, she mustn’t do that!

‘Yes, do let’s go,’ I said.

‘Good! I knew you would want to!’ he said happily. ‘And I

simply can’t face a whole weekend at home with you waiting. I’ll send Ernest a telegram. Let’s have a look at the paper to see what plays are on.’ He rustled the pages of his newspaper to the theatre section and read over it with undisguised pleasure.

‘There’s

Hamlet, Lear

and

Midsummer Night’s Dream

,’ he said in a faintly hopeful tone, ‘but we’ve seen all of them already, of course.’

‘Many times,’ I agreed.

‘So perhaps you’d like something different,’ he continued. ‘How about this?

The Second Mrs Tanqueray

has come back after a break, with the same cast, at the St. James. Do you remember? It was a great hit about two years ago.’

‘I remember hearing something about it,’ I said. ‘It’s one of Pinero’s comedies, isn’t it? We couldn’t go at the time.’

‘It isn’t a comedy. It’s supposed to be rather a powerful critique of social mores. It was the big revelation of the actress Stella Campbell, who’s become very famous since then.’

‘Oh, I remember now! It’s the play about a woman with a past!’ Indeed, I had been intrigued at the time, both by the ‘dangerous’ content and by the flamboyant reputation of the young actress impersonating the main character. But the twins were tiny, and travelling had been out of the question. I had not even had time to think about it again since.

‘Yes, that’s the one. It made quite a splash. What do you say? Shall we go?’

‘Yes indeed, if the Dixons haven’t already seen it.’

Like a magician, Arthur had eased the anxious pressure which seemed to constrict me, and filled my mind with eager anticipation. While not necessarily the most exotic thing in

the world, a day in London, a visit to friends and a trip to the theatre is a sufficiently rare event in my quiet life for it to cause quite a stir and a ripple there. Taking my candle, I went upstairs to pack a few small items in readiness for a departure early in the morning, glancing out of the window as I did so.

The sky was clear and starry, and beyond being pleased that the weather seemed fine, I felt moved by its endless depth. But my joy was suddenly marred by the thought that that infinity of twinkling eyes had looked down so recently on this same garden, on the road which ran past the bottom of it, on the Lammas Land beyond, on the river which flowed and whooshed softly through it, and on the corpse of the dead girl floating there, carried by the current, held by the weeds.

The four of us sat together at a table beautifully laid with white cloth and crystal glasses, awaiting the arrival of the fish. Ernest and Kathleen had quite insisted on bringing us to this little restaurant near the theatre, a newly discovered favourite of theirs, perfect for a late dinner after the play. I settled down contentedly and indulged in feeling experienced and cosmopolitan.

âSo what have you been working on lately?' Arthur asked Ernest, unfolding his napkin and spreading it on his knee. Ernest is of course primarily a physicist rather than a mathematician, and an experimentalist, at that. But Arthur is fascinated by any and all sciences.

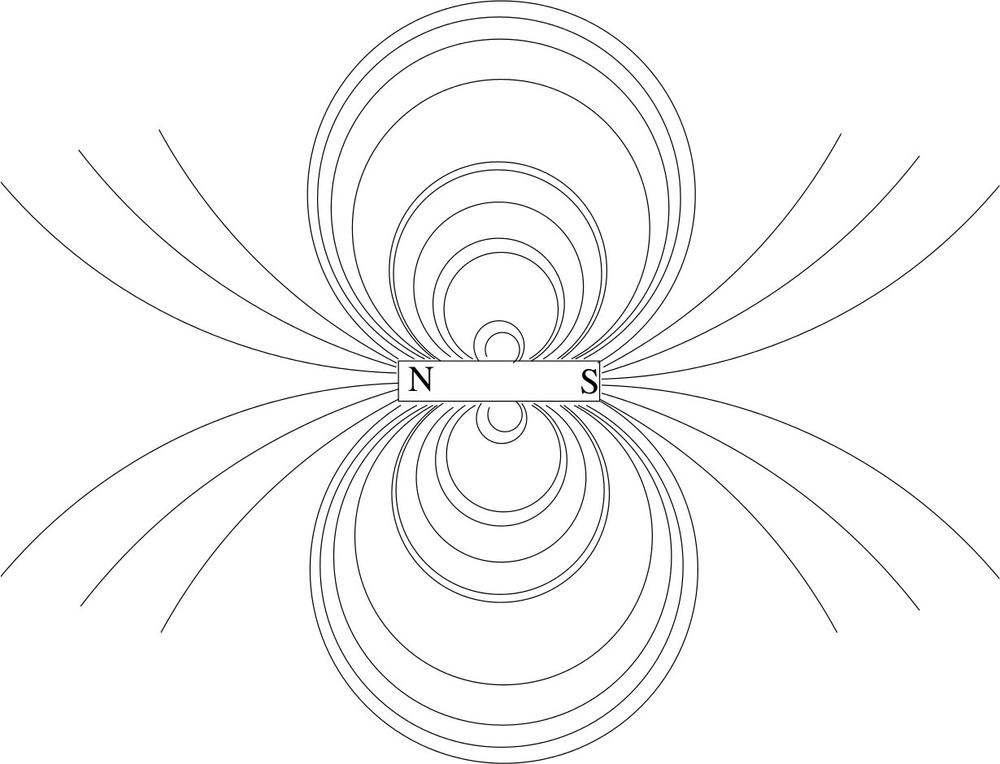

âStill the old magnetism experiments,' replied Ernest. âIt's just extraordinary, the power they have. I showed Kathleen some field lines the other day. You know â if you put iron filings on a sheet of paper and hold it over a magnet, the filings literally shift into a picture of force lines, going from one pole to the other. It looks like this,' and he began scratching out a picture with a point of his fork onto the tablecloth. âIt's extraordinary. It means, you must realise, that those lines are more than just abstract pictures of the directions of force. They represent physical action on the atoms! That's the direction of my present work.' He completed his thumbnail sketch and displayed it to us proudly. âIf you do

this with a magnet, you literally see in which direction the forces of the magnet's poles will pull the iron filings. But if you know the theory, you don't need the experiment!'

âNo physics during meals,' said Kathleen in a hurried whisper, cutting short his enthusiasm as the waiter arrived balancing several dishes on his arm, and hastily rubbing over the scratches with her fingers, âand stop spoiling the tablecloth!' âGot to stop them, dear,' she added, turning to me with a smile, âotherwise they'd be at it all night. I simply can't stand science at the table.' She shook a finger playfully at her husband to smooth the prickle behind her words, but she meant business clearly enough. Personally, I find these discussions quite interesting, although I am but a poor contributor. However, Kathleen preferred to talk about the play.

âMrs Campbell is sublime,' she said. âGoodness, how I love to watch all that spunk and fire up there on the stage for all to see! What a difference with Ellen Terry. Terry can portray the divine in woman as no one else can, I'll grant you that. But Campbell gives you a flavour of the devil.'

âRedhead that you are,' said her husband.

âWell, Mrs Campbell may not be a redhead, but she might well be Irish, if you ask me,' said Kathleen.

âCampbell is hardly an Irish name.'

âNo, but it's her married name. I've no idea what her own name might be. She likes to be known as Mrs Patrick Campbell â it keeps up some semblance of respectability, I suppose.'

âThat is an interesting point,' I said. âIt makes her sound just like the woman in the play.'

âYes, you're right, poor Mrs Tanqueray, trying so hard to tear some respectability from the fabric of her life, and discovering the thing to be impossible. The whole play is about nothing else, really.'

âYes, and yet it's dramatic, tragic even. It's odd that a notion like respectability should take on such importance that tragedy can be based on it. What is wrong with our time? Shakespeare would never have employed such stuff for his plots. Since when has social approval been given the power of life or death over us?'

âOh, well â the power of life or death? Let us not exaggerate.'

âBut yes, in the play it does, doesn't it? After all, Mrs Tanqueray takes her own life at the end. Is she not destroyed by the realisation that her sinful past will prevent her ever obtaining a respectable social position?'

We all four fell silent, trying to understand why Mrs Tanqueray had committed suicide, or, rather, why the author had caused her to do so, after she had managed to pull herself out of the mud of loose living by contracting a marriage with a gentleman.

âI think it was because of guilt. She felt guilty about having revealed to the pure young girl that her fiancé had been her own ex-lover,' said Ernest after a moment.

âNo,' argued Arthur. âShe didn't feel guilty, for it was her own choice to reveal it; she clearly says that she would feel guilty to hide it.'

âIt wasn't that at all,' said Kathleen. âIt was because she realised that her past would not leave her alone, that she would always meet people in society who knew about it. Marriage or none, in fact, respectability was simply out of her reach.'

âI think perhaps it was because she found respectability itself disappointing rather than unattainable,' I said. âHer husband is so stuffy, the girl Ellean is cold and the life is portrayed as being horrendously stifling. I think that once she found it, she was disillusioned and found she could not stand it.'

âMan is a fool,' hummed Ernest, âwhen it's hot he wants cool, when it's cool he wants hot, he always wants what he has not. And woman is worse, of course.'

âHow unfair,' said Kathleen. âWomen's lot is a difficult one, and if they dream of something better, they are accused of not knowing their own mind.' And she pinched his ear, nearly knocking over his glass of wine as she did so. I noticed that droll or tender gestures always accompanied and attenuated the echo of bitterness in her words.

âWell, your lot may be hard,' remarked her husband, âbut

think how you'd hate it if you had to be respectable like Mrs Tanqueray.'

âHo! I am respectable, thank you very much.'

âAre you sure?' he teased. âI don't see you dying of boredom in a country house.'

âThat was only because Mrs Tanqueray had a past! All the truly respectable people in the play live in London and visit the Continent and go to restaurants and have dinners, and no one has a word to say about it!'

âThe whole thing is like a supercomplicated game of chess with a thousand subtle rules,' observed Arthur. âIf one has not done such-and-such before, then it is all right to do such-

and-so

now, but not this other thing, whereas if one has done it before, then such-and-so is unthinkable now.'

âIt is not so complicated as you make out,' said Ernest. âThere's really just a single rule. Stay straight on one matter â let me make myself clear, just a single one â then everything else is open to you.' He blushed as everybody stared at him, open-mouthed at such plain-speaking. Although now that I write the words down, it occurs to me that plain-speaking is not such a good description. Indeed, he did not pronounce the words

stay straight on all that concerns love

. Still, we all understood him perfectly, a sign, perhaps, that our minds are not as pure as they might be.

âNo,' said Kathleen sharply. âThat's far too simple. For one thing, what you just said applies only to women. No, don't deny it, don't even bother. You know it perfectly well. And for another, a woman can be as virtuous as you like, and yet put herself outside the bounds of respectability by her profession. Just take Mrs Campbell as an example. Do you think she could ever be invited to a bourgeois home?'

âWell, an actress,' said her husband, with a little, secret smile.

âThere, you see? You are simply assuming that an actress cannot be virtuous! But why?'

He considered the question for a moment.

âWell, she might

be

virtuous, but she can never

appear

virtuous, because she's public,' he said finally. âThat's the whole point, really, isn't it? Virtue is essentially private.'

âI don't see that,' said his wife. âMrs Tanqueray in the play had lived with a man without being married to him, before she married the stuffy fellow. That was perfectly private.'

âNo, it was public, because everyone knew about it. She had a ââset”, remember? All her friends knew, and they didn't care, because they were just the same themselves.'

âThe real question is, why should we care?' said Arthur surprisingly. âAnd why women particularly, indeed?'

âWhat an awkward conversation,' said Kathleen; âwe keep having to stop and think.'

âIn order not to find ourselves giving out easy formulae or pat words,' I added. âI wonder, if each one of us admitted to the first answer that came into our heads at Arthur's question, if we would not find out something rather disagreeable about ourselves?'

âYou mean when he asked why we care? Because society's dictates have power over our thoughts,' said Kathleen. âThat's what you call a disagreeable thing, isn't it? But we should be praised for at least trying to resist, should we not? I'll admit to my first thought in answer to his question: I thought that we care about respectability in â in much the same way we care about cleanliness. Because we don't like to be soiled. But I know that Arthur could then just as well ask me why living

with a man without being married to him should necessarily be perceived as

soiling

.'

âI thought of those women you see on the street, late at night, in the West End, when you come out of the theatre alone,' said Ernest. âThe ones who come up and say ââCheerio, ducks”, and things like that.'

âWhat things?' enquired Kathleen with great interest.

âOh, nothing important â just things like that. What did you think in answer to your own question, Arthur?' Kathleen looked both fascinated and alarmed, while Arthur, to his credit, looked merely thoughtful.

âI thought that I should not like to share my wife with anyone else,' he said simply. I laughed.

âWhat did you think of, Vanessa? Tell the truth â the whole truth, and nothing but the truth,' ordered Kathleen energetically.

âI remembered a woman I met once who had a little restaurant,' I said. âShe was that kind of woman, and what of it? She was very kind.' I glanced at Arthur, recalling how I had burst into tears on that surprised person's ample bosom at a point when the outcome of his trial was looking particularly frightening. Having never told him about my hasty visit to London, I perceived that he was staring at me in surprise.

âOh, it was long ago, long before we were married,' I said quickly, in order to ward off any questions. âBut seriously, Ernest â you don't really believe that all actresses are immoral?'

âOh, I don't know, and in fact I don't really care to know,' said Ernest. âI like to see them where they are, on the stage, I mean, and shouldn't like to see them in my own drawing room. That's all I mean.'

âThe bourgeoisie may feel like you, but swells do marry

actresses sometimes,' said Kathleen. âWhy, Pinero's most recent play is about that very subject! It hasn't been put on yet â they're rehearsing it now. We're attending a reading tomorrow. It's to be about a rich young man who falls in love with a juvenile-lady from Sadler's Wells.'

âFalling in love is different,' said her husband. âNo one can explain why that happens. You see a hundred women on the stage â why fall in love with one of them in particular? And yet it happens. One among hundreds. I â I saw a lovely Ophelia last month.'

âOh,' said Arthur eagerly. âWhere was that?'

âThe Outdoor Shakespeare Company. It's quite new. Have you heard of them? It was all put together by a bright young fellow called Alan Manning; he puts on Shakespeare's plays, and other plays too, in fields and things on the outskirts of London. They have a kind of tent for when it rains, but they don't play in the winter, of course. It's very fetching, I can tell you. They like to set up their stage where there are trees, when they can. Ophelia actually floated away â literally floated away down a little stream, out of sight. It was most poetic, although in reality, she must have been cold and wet, poor thing.

The Tempest

was impressive as well, with Ariel darting about all over the place, disappearing behind things and turning up somewhere else. He was played by the same girl. Ivy Elliott is her name. A lovely creature.'

âThat sounds both charming and intriguing,' said Arthur. âI wish we could see one of those.'

âYou can,' said Ernest. â

A Midsummer Night's Dream

is running now, out in Hampstead. We haven't been yet.'

âAnd shan't, if you keep on praising that actress to

the skies,' said Kathleen sharply. Ernest crimsoned.

âIs she playing Hermia or Helena?' enquired Arthur smoothly.

âNeither; she's booked for Titania on the programme. She couldn't be Hermia, as she's blonde, nor Helena, as she's rather small. You should go, really. There'll be a matinée tomorrow, even though it

is

Sunday â these bohemians don't respect anything any more! What time did you mean to leave for home?'

âOh, our plans for tomorrow are not firm yet,' said Arthur. âShall we, Vanessa? What do you think? We can go to a matinée and still arrive home before the children are in bed.'