The Ride of My Life (23 page)

My true calling manifested itself as a twenty-one-foot-tall ramp. Everybody has some form of big ramp inside them, waiting to come out.

What’s yours?

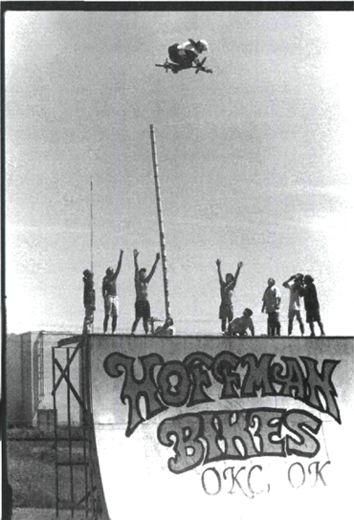

TESTIMONIALADDICTED TO AIR

There’s one last chapter to the twenty-one-foot quarterpipe saga. We were putting on a BS contest on Labor Day in 1994. Mat’s shoulder was really screwed up at the time, and he was going in for surgery just days after the contest. Mat had never ridden the big ramp in front of crowds, and even within the community of hardcore bike riders, a lot of them just straight out thought it was fake. The BS contest was at the Hoffman Bikes park. Mat had a friend of ours with a tow truck drag half of the twenty-one-foot halfpipe over to an area where Mat could set up a runway. The ramp wasn’t set into the ground with a solid foundation. It was totally rigged. At the contest, there were some skeptics who came just to see if it was real or not. It had been a year since he lost his spleen, but Mat wanted to ride and prove it was possible to crack twenty feet. On Saturday it was a really nice day with no wind at all, and he did a couple of no-handers and some very high airs on it, over twenty feet. Mat decided he could top it and declared Saturday was the warm-up day, and Sunday he wanted to fire off some huge airs. I was the guy in charge of towing him on the motorcycle.

After he got warmed up on Sunday, he turned to me and said, “Steve, go as fast as you can.” I knew there was a good chance he could die if he crashed from that height, but Mat was so fixated on it that I said, “Screw it. If we’re doing it, we’re doing it.” I laid on the throttle and went as fast as I could.

He went twenty-three or twenty-four feet high, beating his previous height and blowing everybody’s minds.

After that day, Mat got his shoulder surgery and later went out of town. While he was gone, a windstorm came and knocked the remaining pieces of the big ramps down. They were the only structures in the Hoffman Bikes park that were damaged.

-STEVE SWOPE, FRIEND AND BUSINESS PARTNER

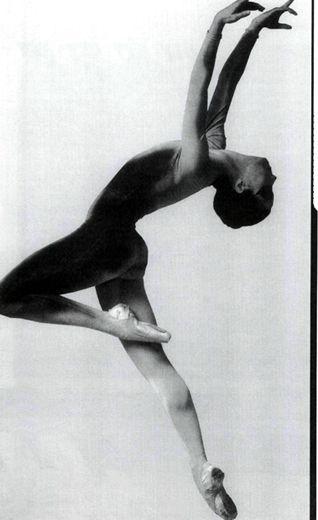

Jaci in the ballet

Prey

. (Photograph courtesy of Keith Ball)

NEW TRANSITIONS

She was pretty. I was shy. Love is stupid. It hits you like a blunt object and converts the rational mind into emotional mush. And the beautiful part about it is, you don’t even care because it feels so awesome.

Jaci worked in a store. I came in Christmas shopping and there she was, looking kinda bored, but with a spark in her smile. I wanted to ask her out on the spot, and at the last second, I choked. I left, kicking myself all the way home. I returned the next day and bought a pair of sunglasses, just so I could interact with her again (and ask her out]. She floored me and put me in a state of heart-pounding, rubber-legged confusion. We chatted for a minute, but I seized up once again. I forgot the sunglasses and exited without her digits or a date.

Within twenty-four hours I’d mustered up the nerve to march back in and be direct. This time I emerged with her phone number and plans to rendezvous, Edmond style: I was taking her to Braum’s, my ice cream connection. Our first date went well. I impressed her with my vast knowledge of toppings, nuts, and flavor selection, but she was fronting slightly and ordered a low-fat sandwich instead of caving in to the decadence of pure sugar. I got a big brown shake, but I was fronting, too—what I really wanted was a kiss, yet didn’t have it in me to ask. Our date wound down to that awkward little parting moment, and either she read my mind, or she wanted a taste of my shake. Jaci leaned over and gave me a smack on the lips. As she drew away, she said—and I’ll never forget this—“

Mmmm

, chocolate.”

That’s my girl.

When Jaci was younger she’d been part of the punk rock scene. We’d even briefly met, when I was twelve and she was fifteen. But in the years that had passed, she’d dropped out and joined a circle of folks who were even weirder than the punks: She was a professional ballet dancer. Jaci had passion, poise, and sophistication. On our second date, I asked her to accompany me for some fine dining and the theater. We met up with Steve and six other bikers for greaseburgers and meat-based humor. Then, we took in the evening’s entertainment, the Charlie Sheen classic

Hot Shots, Part Deux

. The movie was a total cringe-fest, but with the Sprocket Jockeys cracking jokes throughout the film, Jaci had a good time. Date number three was a party at my house, and Jaci was the lone girl amid a roomful of loudmouthed dudes in sweaty T-shirts, bingeing on giant Costco-sized boxes of Ding-Dongs and Fritos. But I knew how to show Jaci I had some class. I cracked open a bottle of champagne for us to share, and at the sound of the cork, the Sprocket Jockeys posse all began yawning and checking their watches, leaving us alone. It was almost as if they’d been waiting for a signal.

She was the one. After seeing each other for a couple of months, my soul mate radar was lighting up, big time. Historically, my track record with girlfriends was the same—whenever things got too deep or complicated, I hit the “eject” switch. But this time was different. I was crazy about Jaci. I could see the cute house with the white picket fence, the 2.5 kids, the fancy little soaps in the potpourri basket in the bathroom. The more time we spent together, the closer we became. Jaci was the first person I’d been able to open up to since my mom had passed away. She helped defrost my heart, and I was finally able to be happy inside again. Everything was going great… and then I got jacked: Jaci was asked to dance for the Ballet Mississippi. She’d be gone for several months. I knew better than to try talking her out of it, because she was as passionate about dance as I was about bikes. In fact, that was part of the reason we got along so well. Despite the surface differences between bikes and ballet, the two activities shared a similarity at their core: Each attracted a certain type of totally committed freak who was determined to find the balance between mental and physical worlds. Jaci’s move to

Mississippi was a great opportunity, one she couldn’t pass up. The downside: Between her schedule and mine, we were looking at months of separation. Rather than break off our relationship, though, we decided to stay a couple, distance be damned.

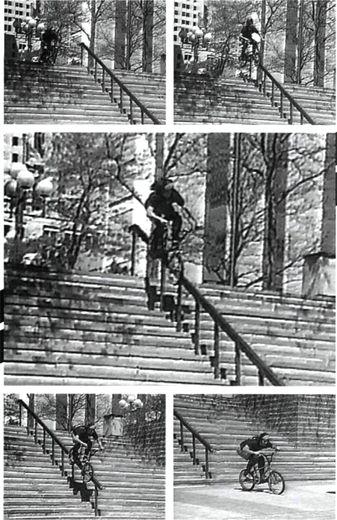

I visited Jaci a few times while she was dancing with the ballet company. I’d go out and ride the streets of Jackson, toting a Polaroid camera with me to take photos of the handrails I was trying to slide. I would place a picture at the bottom of the rail. My technology was simple: If I fell and got knocked out, I’d come to and see the photo there to remind me who I was, and why I’d woken up lying in the street next to a bicycle.

I was starting to have a real problem with getting knocked out. After I learned 900s, I put it on my to-do list, once a week. Then it became once a session. On vert, you can’t get more gnarly than a 9. It’s pure commitment, and if you fail, you take the brunt of the impact with your head and shoulder. You know there’s only a fifty-fifty chance you’ll make it, but you have to convince yourself to try 100 percent. The more 9’s I spun, the more frequently I found myself waking up in the flatbottom.

I suffered a serious incident with a 900 at the BS contest in San Jose, California, in 1992. I was the last rider in the final class of the weekend, pro vert. It was the closing trick of my last run, and I rolled in focused on firing off a 9. I didn’t make the spin, came in backward and sideways, and channeled the full momentum of my upper body into the flatbottom. I spanked the ramp with my head and knocked myself out, bad. The contest energy in the building came to a grinding halt. The music shut off, replaced by an uneasy lull as everybody wondered what just happened. As Steve later put it, “we watched Superman fall out of the sky and get knocked out cold.”

My friends brought me around, trying to make sure I was okay. I came to amid the confusion of the contest environment and couldn’t remember who I was, why I was there. I’d lost all my recall, and the first thought to return was the most powerful memory—that my mom had died. Totally out of it and in a concussion daze, I broke down and started crying. In my mind, the scars reopened, and I had to again go through the most terrible thing that had ever happened to me. Riders were milling around to find out what was up, if I was okay. I couldn’t grasp the concept that it was

my

contest, and I was in charge. People wanted to know what the scores were for the finals. Until the results were tallied, nobody could get paid or know who won. I was being asked questions I had no idea how to answer. “Somebody go find Wilkerson,” I said, half-sure we were at a King of Vert comp and the year was 1988. Thank goodness the riders on the scene were understanding enough while I got my wits back. The incident really freaked me out, and for a long time thereafter the first thing I would try to remember when I came to after knocking myself out was,

Don’t try to remember anything.

Steve, Chuck D, and the BS contest crew had their work cut out for them that day, taking care of me, trying to maintain control of the event, and closing things down afterward.

This handrail in Kerr Park in Oklahoma City was the first big rail I ever slid. If you go there now they have blocks riveted down it so you can’t slide it. Damn surveillance cameras.

Dennis McCoy has had an excess of success during his career for being consistently one of the best overall riders—a true testament to his riding skills. Dennis was the first guy to rule ground, street, and vert all at the same time.

Dennis and I both got the same stamps in our passports three times during a six-month span in 1992. First, at the World Championships in Budapest, Hungary. It was there that he took the worst slam I’ve ever seen anyone suffer. He slammed a flair and his body bounced at least one foot off the flatbottom after the impact. I joked with him later that it looked like he was trying to do a loop on the halfpipe and reenter down the opposite transition. He somehow got up under his own power, but later at the hospital it was discovered he’d broken his back. During my run I got a flat tire and had to borrow his bike. It was so small and set up so weird I could barely ride. Getting on a strange bike and having to adapt as you roll into a ramp is like trying to do cartwheels through a car wash holding a watermelon: It’s awkward. Using Dennis’s Mongoose, I dropped in and aired a couple feet out feeling incredibly dangerous. I got a pump off the wall and threw a no-handed 540, half-expecting to go down in flames. I pulled it by some mystery, linked a couple more tricks in my run, and decided it was best not to question that miracle. I ended up winning the contest, and as an odd bonus I was declared the world champion of mini ramps.

Our next overseas travel adventure was the Rider Cup in England. The Cup was one of the first contests to blend skate and bike events together under one roof with a street course and vert ramp. Riders and skaters from all over the world were there. It was a bad contest for me for a couple of reasons. First, it started out bad—I’d blown up the transmission in my car on the way to the airport. But by the time I’d arrived in England, I was ready to work out some tension. I found the vert ramp to my liking and was quickly clocking airs fourteen feet out, doing high tailwhips, 540 variations, and keeping my legs busy kicking through, around, and over my bike. My runs were interrupted by a steady stream of shoulder-shearing slams, flat tires, and more bike borrowing. At the end of the day I took myself out for good with a flair to chainring hangup—I pitched forward into the flatbottom and stuck out my arms to break my fall. Bad move. I didn’t know it at the time, but I’d completely torn the rotator cuff and inherited arm and shoulder problems forever. I’d already had one surgery to repair my right rotator cuff, so I had a sinking feeling I was in for some more time under the knife.