The Ride of My Life (25 page)

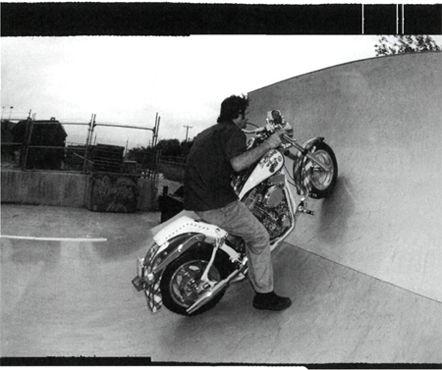

Evel Knievel hooked me up with a deal on one of his signature CMC Motorcycles. I’m on the way home from the dealers in this shot. They made less then fifty of these bikes. (Photograph courtesy of Paul DeJong—aka the Coach)

ESPN WHO?

My early experiences with ESPN were as a rider. It was a great way to learn how dangerous the power of TV can be.

Let’s rewind to a bored afternoon backstage on the Swatch Impact tour, in Philadelphia, circa 1988. It was a media day. The rest of the athletes and I were all waiting for a local newspaper or TV news station to arrive and interview us. Often the journalists outside our sports had no idea what we did and made rookie mistakes like calling the halfpipe a “half-pike.” The show business philosophy about coverage is, “It doesn’t matter what you say about me, just make sure you spell my name right.” To ensure accuracy in this matter, Swatch set up our backstage area with a chalkboard, and written neatly on this board were the names, ages, and hometowns of each skater and biker. On this particular day as we waited for the press, one of us noticed that the only guy with a flashy nickname was Mark Rogowski, who went by the moniker “Gator.” I

think maybe it was skateboarder Chris Miller who picked up the chalk and began scrawling up some new nicknames on the board. We all began chipping in, and “Gator” was changed to “Carl.” A variety of animal names were conjured up for the rest of the riders and skaters: Chris Miller was “The Chimp,” Brian Blyther became “Pterodactyl,” and me, I was labeled “Condor.” We laughed and joked and thought our silly pranks with chalk were awfully clever.

Six months later in Canada I pulled the 900 at the Ontario KOV contest. By fate, an ESPN crew had showed up to film the comp—it was the sports network’s first foray into televised freestyle coverage, and they were out of their element. The ESPN announcer looked like a TV meteorologist, and because the film crew wasn’t part of the scene, they didn’t know who was who or what tricks were hot. To them, we were just nutty kids riding little bikes on a wooden boomerang-shaped structure. But after I pulled the 9, they sensed from the crowd reaction that something important had just gone down. The producers began asking about that kid who did the spin. Brian was the first to answer and offhandedly remarked, “Yeah, that’s the Condor.” Never ones to overlook the allure of a spicy nickname, ESPN latched onto

Condor

and ran with it, introducing me to the world as the incredible twirling bird, Mat “The Condor” Hoffman. I’ve never lived it down. The lesson here is, be careful of sharing your inside jokes with TV crews.

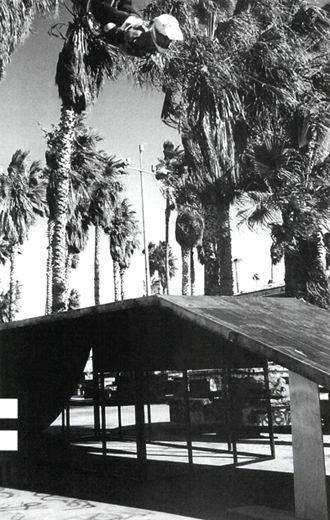

My next contact with ESPN was six years later, in 1995. They’d launched a new spin-off network, ES??2, with a mission to cover sports that were younger, faster, edgier, and more action-packed—an umbrella encompassing everything from lumberjack grand nationals, bungee-corded kayak drops, rodeo clowing, modified snow shovel racing, and of course, bike stunt riding. The network initially contacted me to do a commercial to promote some vague event they had cooking. I was excited that somebody wanted to put bikes on TV—a rarity at the time—so I didn’t really ask questions. The shoot was at Muscle Beach in Venice, California. It was blistering hot, and the sun reflected brightly off the blinding sand. At the director’s request, I did one hundred consecutive backflips that day. Before each one I squinted at my friend John Pova and uttered the same line, “Watch this, I’m going to do a backflip!” It was a long day and doing the same trick over and over was pretty boring, so I had to find a way to entertain myself.

In the weeks that followed I found out just what ESPN2 was up to. The thing I’d helped advertise was their concept for a new contest series, called the Extreme Games (later shortened to X Games, when the network discovered they couldn’t copyright the word

extreme

). The comp was to be a modern-day made-for-TV mini-Olympics, with skateboards, bicycles, in-line skaters, wakeboarders, and a fistful of risky and frisky sports. The inaugural Extreme Games contest site was in Providence, Rhode Island, a tourist-attraction-type town known for being the home of the nation’s first circus. ESPN2’s plan was to set up a bunch of ramps, TV

cameras, bleachers, and banners, then invite a few hundred pro skaters, bikers, and miscellaneous freaks to converge on the sleepy city, creating a whole new definition of the word

circus

. The bait was a pile of money and a challenge: Try and get it.

From the word Go, it was apparent the contest was going to be an extreme learning experience for everyone involved. The network had the almighty power of Mickey Mouse-based media dollars behind them, but it was clear the Disney subsidiary didn’t know shit about skaters, bikers, or holding a fun event. The contest was at its best, a big TV show where athletic rivalries were fictionalized to fit in with the network’s approach to dramatic sports coverage. At its worst, the contest site became a ticking time bomb of tension between the participants and the appointed glad-handers, producers, cameramen, security guards, and various production staff involved. I was one of hundreds of athletes competing in the Games, and I used my personal experience as a benchmark for how stupid things could get. Before the games even began, competitors were notified not to wear logos on their clothing—ESPN didn’t want to conflict with their TV sponsors. I printed up a Fugazi-inspired shirt with large,

THIS IS NOT A HOFFMAN BIKES T-SHIRT

typography across the back. I went to Rhode Island braced for trouble, and sure enough, it found me. I got kicked out twice in less than twenty-four hours by the same rude dick.

The first ejection was because I was helping Dennis McCoy’s wife, Paridy. She was being hassled by a beefy jerk, who wouldn’t let her into the rider staging area because she had the wrong color badge. ESPN was very big on badges, wristbands, levels of access, and security. I stepped in to ask the guy to have a little respect. I introduced Paridy and said her husband was starting his run and she needed to be close by in case he got injured on the dirt jumps. “Not without a badge, buddy,” said the sucker with authority. I took my badge off and handed it to Paridy right in front of him. Paridy tried to pass through and he became a little aggressive with her, so I got up in his face. Guards were called, and I was escorted off the grounds by the elbow.

The next day was the vert contest. ESPN2 had provided the biker group and skater group with their own vert ramps; there were strict practice and contest schedules. I dropped into the designated bike vert ramp and noted they’d put sand in the paint; their logic was that bicycle tires would stick to the surface and allow us to pull off even wilder stunts, which would make for better TV. It was a good idea in theory, but in practice, it sucked. They never considered what it would be like to fall and slide down the tranny. Warming up, I slammed a couple times and the surface ripped my pads off and ground my skin like a giant piece of sixty-grit sandpaper. Before long, the bikers had dubbed the ramp

The Skin Eraser

. “Screw this,” I finally said, noticing there were only two skaters riding the skate halfpipe. Their ramp was built sans sand. I went over and asked the skaters, Mike Frazier and Neil Hendrix, if I could join them. They were cool with me riding, so I dropped in and took a run. Suddenly the same jerk who’d kicked me out the day before was back, squawking at me to stop immediately, because I was practicing on the

wrong ramp. I kept riding, hoping he would go away. The guy was too stout to make it up the rickety ladder to the decks, so I stayed up there and pretended I hadn’t noticed the scene he was making. Neil, Mike, and I continued sessioning, and the rule enforcer was getting more frustrated. Finally he strode into the flatbottom of the ramp to “block” me from riding across while he continued yelling. I did airs around him—a 540, a couple of high pumps, to a tailwhip. I did a fakie and rolled backward, taking us both out. I was marched out of the rider’s area by security once again. The rest of the bikers cut the organizers no slack, complaining loudly and bitterly about the bicycle halfpipe sucking. Several of my friends protested that I’d been collared and tossed out of the contest area and sarcastically asked the producers if they’d throw Tiger Woods off a golf course. ESPN recognized they’d goofed, and I was un-kicked out. By that point I was so pissed, I converted my anger into energy and won the vert contest. It was held, by the way, on the skate ramp.

Doing a fakie on my Evel Knievel signature motorcycle.

Standing on the podium with a gold medal around my neck, I had another reason to be revolted: I was handed a giant check to pose for the cameras and noticed it was for $12,500 less than the check given to the guy who won the mountain bike event.

After their first contest had been broadcast, ESPN2 got an earful of criticism from the athletes and the action sports industry. The network also found out Steve and I had been putting on the only national bike stunt contest series for the past four years. They were real curious as to what we thought of the Games.

I got a letter from the same jackass who’d kicked me out of the contest. Without acknowledging that he’d booted me, the producer stated in a chatty tone they wanted me to be a consultant with their organization, run the bike events, and help them put on the Extreme Games. He ended his chipper correspondence, “Extremely yours” followed by his signature. I just about heaved. I was concerned all the work we’d put into running the BS comps over the years were going to be undone by a group of clueless TV execs. I could ignore them, but they weren’t going away. And on the bright side, at least I now had the name of a guy on the inside—I didn’t have to battle a faceless cable television monolith.

I barraged my extreme friend with a long list of everything that was wrong: From blaring Top 40 music (and, sometimes, no music] during runs, to pointless ramp placement and park setup, sand in the paint, low pro purse money, and lack of respect for the very talent they were featuring as their entertainment. There was no sugar-coating. I included a list of conditions on which my involvement hinged. And I signed my letter “Fucking yours.” Yeah, I was an ass—but I needed to let them know I couldn’t tolerate overt stupidity in my sport for the sake of TV industry meatheads chasing snack food sponsorship dollars.

Ron Semiao, the creator and developer of the X Games, is one of the true visionaries at the network. He read my letter and said, “You’re right.” Ron was smart enough to realize that action sports could be groomed into the next big sporting category. He also understood that the network could do a lot of things well, but they didn’t know enough about the new sports they were covering to walk in and be accepted as an authority. To establish themselves as part of the action sports culture, they needed support from within. And first, they needed to prove themselves.

ESPN2’s primary concern was to create a product that was living room friendly; that is, basically remove all the slow, inconsistent parts of a contest and create a pure adrenaline, high-action TV format. My concern was to make sure that while they did their job, they didn’t accidentally or purposely suck the life out of my sport by trying to edit it for television and change the focus for a new, broader audience. I saw right away the positive and negative aspects of a network. For the first time, the bike riding community didn’t control things. I was fine with Ron and Co. saying they wanted to make history—as long as they were careful not to

overwrite

history that I’d been part of since I was twelve years old. But if Ron’s vision was done right, we could evolve the BS series into the qualifying events for the X Games, bring in more money for the riders, put

together dream courses and ramps, and still have a great time while giving some exposure to an underground activity. There would be a learning curve as the corporate side experienced our culture and we interacted with their world.

One of the hundred flips I did at Venice Beach for the first X Games commercial.