The Ride of My Life (6 page)

I was so into freestyle that I wore Dyno BMX pants to school, regardless of any fashion laws I was violating with my dangerously bold color themes. I treated my bike like

a priceless artifact, polishing my seat, grips, and the surface of my Tuff Wheels with Armor-All liquid silicone sealant—a substance that kept my bike shiny, but incredibly greasy. Taking my cousin Tom’s engine performance tips even further, I began experimenting on my bike with power tools. I ended up accidentally boring a hole into my forearm when I attempted to drill through the length of the handlebar stem bolt, to run a brake cable through it. This one hurts to admit, but I used to put my bike in bed, under the covers, and fall asleep next to it.

Over a couple of golden summers, Travis and I made the transition from grommets to bona fide bike shop rats. I forged a few of my lifelong friendships inside that building—guys who I still work with nineteen years later, like Page Hussey and Steve Swope. The crew also tended to congregate at my house, and I’m certain I wouldn’t be where I am today if it weren’t for the incredible support of my parents. We needed to rebuild our six-foot quarterpipe to eight feet? The construction site was at our place. And later, when it was crucial we get a halfpipe? Mom and Dad had no problem letting us build it in the backyard, or with allowing all the locals to session it. Our freestyle fever was matched by Mom’s enthusiasm—whether it was making us custom riding shorts or helping us figure out how we could put on a trick team show—my mom was at the heart of it. When our small band of friends formed the Edmond Bike Shop Trick Team, my mom was so proud.

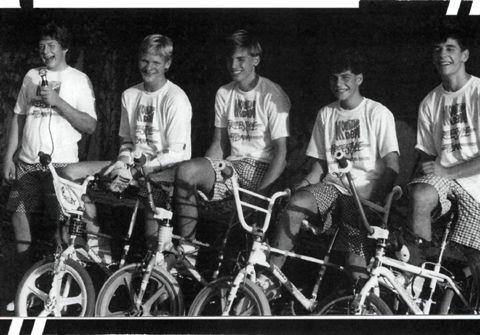

The Mountain Dew team [left to right): Josh Weller, Me, Steve Swope, Keith Hopkis, and Travis.

The team consisted of Ron Dutton’s son, Chad, and Jeff Worth, Josh Weller, Eric Gefeller, Travis, and me. Our first public performance was at a nearby park, after a parade. We put a fancy paint job on our six-foot

BMX

Action quarterpipe and wrestled it into a truck; then it was hauled via parents to the demo site. It was the first time I’d ever ridden a ramp on cement. It was a show filled with mistakes and nervousness, but we really got into riding in front of a crowd. It only took one show for us to realize we needed a bigger, more transportable ramp.

A carpenter was hired to make an eight-foot quarterpipe. He convinced us there was no way to make an eight-foot radius [there is], so we got a nine-foot-tall ramp instead. We called it “The Wall.” It was massive, way bigger than standard ramps of the day. We didn’t know any better so we rode it, eager to do more shows. My parents kept watch over the community calendar, and if a festival or public gathering was approaching, they’d make some phone calls and get us a gig. The Edmond Bike Shop Trick Team posse shifted members when Chad Dutton and Jeff Worth dropped out and were replaced by Steve Swope and Keith Hopkis. We’d travel out of town, performing wherever we could. It wasn’t a moneymaking endeavor; we just did it because that’s what freestylers were supposed to do.

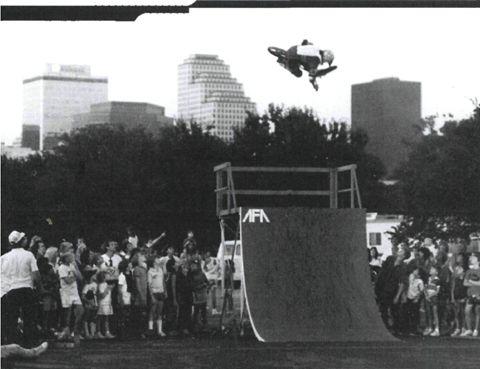

Austin, Texas 1986. It was a demo for the Texas AFA—one of the first shows outside of the Edmond Bike Shop and Mountain Dew shows I was asked to ride in.

My habit was starting to pay off in other ways—my airs were getting higher, shooting out of the ramp and into the seven-foot range. I invented my first variation, a switch-handed aerial. Another arrow in my quiver was the frame stand air. I’d do an air, jump up from the pedals to the top tube, and ride out doing a frame stand. The no-footed can-can had become the trick of the era when California pro Mike Dominguez unveiled it during the King of the Skateparks contest—

Freestylin

’ magazine ran a full-page photo of the trick. No-footed can-cans were pro level and rumored to be incredibly hard to pull. During a show, I accidentally did one when I tried my frame stand air and missed the top tube, flinging both feet out sideways. It was a mistake that inspired me to start practicing them, and before long I could extend both legs in photo-perfect form.

In 1985 a Mountain Dew commercial started popping up on TV, which featured freestyle greats like Ron Wilkerson, Eddie Fiola, and RL Osborn. Its flight lasted all summer, and Travis, Steve, and I would surf around channels trying to avoid the shows but find the advertisement. My mom saw how psyched we’d get and called the local Pepsi bottling and distribution center to talk about creating a local form of promotion in sync with the commercial. A few days later we set up our ramp in the Pepsi distributorship parking lot and did a show in full uniform for a couple of executives from the plant. They were stoked, and we were in. We painted a big Mountain Dew logo on our ramp, got jerseys and stickers, and they set us up with a sponsorship through Edmond Bike Shop to keep us flush with parts and inner tubes. In exchange for the Mountain Dew support, we’d do shows at random supermarkets that sold the soda.

Competition was another aspect of the freestyle scene. The American Freestyle Association (AFA) was starting to take root, and we got word of sporadic, organized local competitions happening around Oklahoma. I entered my first contest as a novice. It was in the days when we still rode the six-foot quarterpipe, before we built “The Wall.” The contest had an eight-foot-tall ramp, and I wasn’t used to the height. I’d hit the ramp really fast and crashed every time. On one of the slams I held onto my bars and my brake lever pinched my fingernail like a pair of pliers and tore the nail clean off. That one sucked.

By the spring of 1986, freestyle gatherings were becoming an extension of the sport that we read about in magazines. The biggest contests and tours were often covered by the bike magazines, but that seemed like a fantasy world compared with the scene in my state. On a lark, I sent a photo of me on “The Wall” to

Freestylin’

magazine and they printed it in their letters section. It was a shot some lady took at a local show; I was clocking a one-footed air about seven feet out. I was psyched.

A couple months later the Haro team came through Oklahoma, and Steve Swope’s mom drove us to the show, to check out Tony Murray and Dennis McCoy. They let us ride their ramp with them before the demo, and I unleashed everything I had to impress the famous factory superstars. They paid me the ultimate honor, asking me to ride with them during their demo. This was the equivalent of an aspiring local guitarist being asked by Metallica to come onstage and jam. Afterward, Dennis took Steve and me to dinner and announced that he wanted to bring me on the road for the rest of their tour. I was so blown away I could barely stammer out “sure,” and during dinner I was already mentally packing my gear bag for the tour. Dennis made a phone call to tell the guys at Haro the good news. He came back with a weird look on his face that said the call hadn’t gone well. Today, I understand how silly it must have sounded when he phoned in his request: “Hey, I found some random fourteen-year-old kid in Oklahoma who rules. Can we pick him up and take him on tour around the rest of the United States?”

In August of that year, I got another chance to mingle with the elite, factory-sponsored riders at the AFA Masters Series contest in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Any local notoriety I had because of my riding had been doubled after the Haro show incident and getting my picture printed in the letters section of

Freestylin’

. Suddenly my peers dubbed me a local hotshot, and it was time to compete against riders from all over the country. I was expected to show these guys what Oklahoma City kids were made of. I was so nervous I spent the contest morning barfing up breakfast. During my run, my jittery hands could barely flutter back to my grips. When they announced the results, I couldn’t believe it: I’d won my age class, 14-15 Expert Ramps.

I missed the next few contests after taking myself out of commission. I was practicing 360 drop-ins at a local show and was just getting the trick down when I slammed so hard I suffered a fourth-degree AC joint separation on my shoulder. I shattered my left collarbone so badly they had to remove a large chunk of it—at least it happened right next door to a hospital.

On June 29, 1987, there was a massive AFA contest scheduled in New York’s Madison Square Garden. I’d been riding every day from sunup to sundown, and my friends told me this would be the comp where I’d earn a factory sponsorship. I bet my friend Page five dollars that he was wrong. Then, just days before the event I crashed and broke my toe. I taped my foot up so I could ride in the contest and flew to New York with my dad, mom, and sister. I was nervous to be entering but stoked to be present around all the other riders. I hit it off with Skyway rider Eddie Roman after meeting him in the stands, and we passed the time heckling bystanders and cracking corny jokes. When it was time for my run, I put the butterflies out of my stomach, bowed my head down, and cranked toward the quarterpipe. A slew of can-can look-backs, switch-handers, no-footers, no-footed can-cans, and everything else in my

arsenal poured out of me. Out of nowhere, the arena burst to life with applause and camera flashes. I won 14-15 Expert Ramps and lost the five dollars to Page.

Before I’d caught my breath after my run, the team managers from Skyway and Haro had approached with sponsorship offers. Haro wanted to try me out on their B Team, and let me work my way up. Skyway didn’t operate like that—I would be part of their factory squad and get to go on tour, get flown to contests, and draw a salary.

I signed on the line with Skyway and was soon flown to their headquarters in Redland, California. The team manager had been hyping my skills, and the owners wanted to witness their new kid in action. During the show I slammed so hard I snapped my other collarbone and wound up in the hospital again.

Luckily, they decided to keep me on the team.

TESTIMONIALLIFESTYLE SUPPORT

I didn’t actually meet Mat until he was signed up on Skyway and came out to do a show at Skyway’s local bike shop. He arrived with his mom, dad, and sister. I thought it was cool that they all came out just for this little bike shop show we were doing.

When Mat was warming up, he looked a little sketchy on the new bike. He landed an eight-foot air too far over the nose and got ejected from the transition onto his shoulder and head. He was down for the count with a broken collarbone and concussion. He sat dazed in the Skyway van, not really recognizing any of us for quite a while. His family was remarkably calm—I guessed they’d seen it before.

I was really surprised at how strong Mat’s family support was. They never tried to steer Mat away from what he loved. Not many parents could watch their kid break himself up and believe that it would lead somewhere. They saw it in Mat, even way back then.

-MAURICE “DROB” MEYER / SKYWAY TEAM PRO. BIKE RIDERS ORGANIZATION COFOUNDER

When you’re performing on tour day after day, you’re so happy when rain gives you a day off. Here’s Team Skyway rejoicing. (Photograph courtesy of Maurice Meyer)