The Ride of My Life (29 page)

I have trouble waiting twenty seconds in front of a microwave for a burrito, so trying to sit and wait calmly for my chute to pop while sizzling toward earth can be a test of patience. This time my pilot chute seemed to be whistling and sniveling above me for an extra long time, so I raised my right arm up to shake the risers (the ropes connecting my chute to my body] and see what the …

WHOMP!

My chute deployed and jerked my body violently, the force from the risers instantly knocking my right arm out of socket. It was one of those Homer Simpson “

Doh

!” moments as I floated through the sky, unable to steer my parachute and in an awkward situation. After considerable struggle, I popped my arm back into socket and regained control. I steered in and landed without further incident, then spent the rest of the day in an endorphin overload daze.

A week later I was jumping at my home field, Paradise Paracenter in Norman, Oklahoma. I had a new rig. This one was a Sabre 150, state of the art. It flew like a Ferrari drives. You could crank off lightning turns, and if you pulled one toggle down to your foot, backflips were possible with the canopy open. The difference between my old Pegasus and my new Sabre was that the Sabre’s pilot chute was hooked up to a kill line. After the pilot chute popped open the main canopy, the kill line disengaged the tiny pilot chute. With only one canopy open, you were free to haul ass and zoom around until it was time for what you hoped would be a gentle, pinpoint landing.

“Look for the red canopy,” I told Jaci. She’d come down to Paradise with me while I got in a couple of quick jumps. I had a jumpmaster assemble my rig, including the kill line. With the rigging taken care of. I carefully folded the canopy and packed it into the backpack-like apparatus called a container. Then I put it on, adjusted the shoulder and thigh harnesses, and was ready to jump.

After exiting the plane, I spent fifty seconds lofting my jive and was ready to release the pilot chute. Without warning, my kill line collapsed before it pulled my main canopy open. I was free-falling, towing my bag behind me as I tried to sort things out in my head.

Now what the hell

? I considered shaking my risers but remembered the outcome from the previous week. As I attempted to solve the problem, the solution became clear: Cut away from the defect chute and deploy my reserve chute. My altimeter was bleeding off hundreds of feet, and I’d hoped my arm didn’t pop out of its socket as I fought the wind and my parachute. It was like one of those Extreme Magic specials on Fox TV, only not fake. I normally pop the canopy around the twenty-five-hundred-foot mark, but when I looked down I was at fifteen hundred and falling fast. I ended up cutting it away and got my reserve open at eight hundred feet. That’s about eight seconds before I hit the ground like a sack of turtles, roughly the same amount of time it took you to read this sentence.

I drifted in for a landing with the reserve canopy, which is silver. Jaci was on the ground, looking nervous and squinting up toward the sky, still searching for the red one.

Immediately the jumpmaster guys were on the scene, heckling me. With less than fifty jumps in my logbook, I was still a rookie. I had no idea what happened, but the jumpmasters suggested I failed to cock the kill line, something you’re supposed to do as you pack your chute to ensure proper deployment of the canopy. I had cocked it, definitely. I was positive. So what had caused the mishap? As I gathered up my chute another veteran jumpmaster walked over and examined my rig. “Hell, this thing was put together wrong.” He said. “You jump this again, it’s not opening a second time. You’re jumping out of a plane with a parachute guaranteed to malfunction.” His words hung in the air. For their error, they offered to pack my reserve chute for free. Apology accepted. I saved $40.

The next high-risk exam hurt. I was out the door at ten thousand feet with another Oklahoma local, Joe Bill. We were doing relative work—basically just practicing flips, we docked together, and then broke away. I threw my arms back into a delta track position to maneuver in closer to Joe and pandemonium broke loose. My right arm obviously didn’t get the interoffice memo to stay

in shoulder socket while free-falling

. The roaring wind blasted my arm, and I felt it give out. Instantly I careened out of control like a rag doll, arm dangling and flapping uselessly out of the socket. The whole point of skydiving is to become a wing. Your limbs are crucial in maintaining body positioning when you’re free-falling, so if you lose command of an arm or a leg, it’s like a plane without any aileron rudders. No control at terminal velocity means you’re a human ball of laundry inside a clothes dryer, set to tumble high. This in turn affects your equilibrium; your only real reference point up in the middle of nowhere is the plane (long gone by then) and other skydivers.

I had no idea where Joe was, but I had other concerns. First, get a hold of my flopping arm and pin it down to my chest in “National Anthem” position. This helped stabilize me, a little. I’d burned about a thousand feet of altitude, and the ground was starting to get more detailed. The only problem was, my jacked arm was the one I needed to deploy my chute. My pilot chute was located on the back of my right leg. With my right arm dislocated, the only way to deploy my chute was to reach it with my left arm, and the chute seemed to be just out of reach. It was like a complex physics problem:

“I’m traveling about 160 miles per hour, one-armed, unable to deploy, and I have no idea if the guy I jumped with is directly above me. Hmm …”

There was only one route out. I started reaching for my pilot chute, trying to snatch the release while still holding my bad arm to my chest. It was comic book style:

“Can’t…reach… pilot chute… must… deploy….”

I finally snagged it and popped my canopy and thankfully didn’t collide with Joe as I rapidly decelerated. “

Ahh, cool. Now I’ll get my arm back in,”

was my first thought. Steering with dual toggles, applying the brakes, and landing using only one arm is pretty squirrelly. As I floated downward,

trying to grunt and

umph

my arm back into socket, it was clear I’d have to initiate Plan B: half-brake all the way in. My last thought before impact was

Ah, God. This is gonna hurt

…

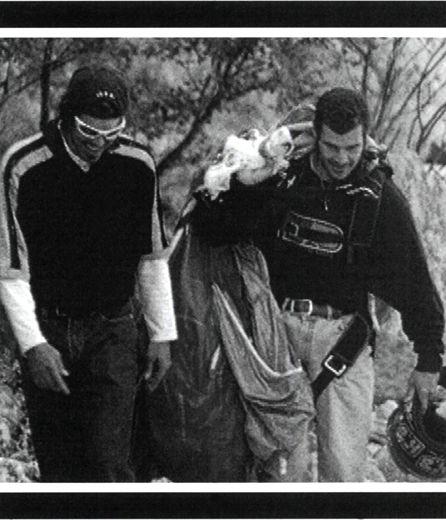

I hit the ground with a puff of dust and slid into home plate. My chute gathered and ruffled around me as I just lay there on my back, looking up at the sky and breathing hard. Fuck. One of the jumpmasters finally came over and asked, “What’s the problem, chief?” I open my eyes and replied, “Hey, could you put my arm back in for me?”

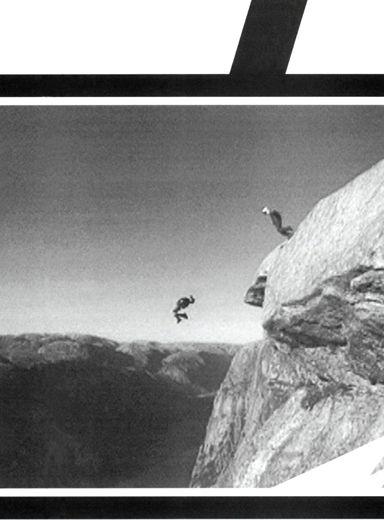

I continued nourishing my skydiving habit, soaking up live-and-learn lessons on the fly. I found myself frequently in conversation with my friend John Vincent. John is an undersea welder and Jedi Master of B.A.S.E. jumping. He has thousands of sky dives and more than five hundred B.A.S.E. jumps under his belt. He’s pulled off some burly ones like leaping off the Twin Towers, the Brooklyn Bridge, the Superdome, and more—and gotten away clean. Since most U.S. structures are private property, you not only need the skills to avoid being killed, but the stealth and willpower to trespass while making jumps. John wasn’t so lucky when he suction-cupped his way up the St. Louis Arch in the dead of the night and leaped off at first light. The footage aired on the news and a federal arrest warrant was issued; he turned himself in and got locked up for ninety days, a criminal. But to me he’s a guy who lets his passion take over, and I think this common link is what made us friends. John and I began scheming B.A.S.E. jumps, concocting super big stunts that I knew if we were to attempt, either one of us could wind up dead.

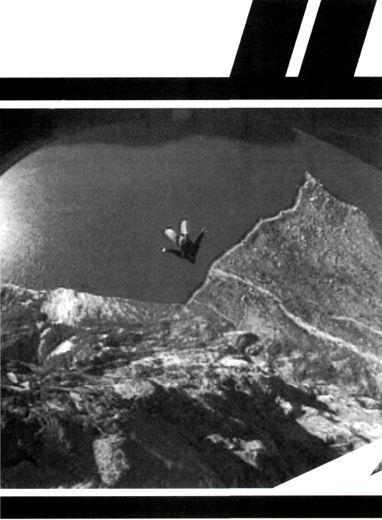

I was immediately attracted to the idea of B.A.S.E. jumping because of the similarities between B.A.S.E. and bikes. When you ride, you start to see things differently. You tap into a new part of your consciousness. You don’t see a rail to grab onto when you walk up a set of stairs—you see what you could do with your bike on it. You count how many steps there are, and determine if it’s steel or aluminum [because 4130 chromemoly bike pegs slide faster on steel surfaces]. You check it for obstructions, do a visual sweep for security guards or surveillance cameras, and then make a mental note of the rail location. If you ride it once, you never forget how to find it. Think of Manhattan, and imagine how many handrails there probably are there. I guarantee the local riders can take you to every single rail that’s not a bust. B.A.S.E. jumping is the same way. On tour, I’d look at buildings, antennas, spans, and earth (B.A.S.E.) in every city to scope out good exit points and whether there was a decent landing space. I began to see the world in a totally different way, what psychologists call a paradigm shift. I liked it.

When I was in Shanghai, the only thing I could think of was what they would do to me if I jumped off the Orient Pearl TV Tower [1,535 feet]. The population there seemed pretty mellow, but the military/state/cops struck me as a serious bunch, not to mention the fact that my Chinese language/negotiating skills are terrible. So I kept my size twelves planted on the sidewalk for that trip. Whenever I go to Japan, I salivate over the Tokyo Tower (1,026 feet). In Kuala Lumpur, the Petronas Towers (1,483 feet] get my mind whirling, and of course the desire to throw myself off the Eiffel Tower (986 feet) is a thought I always entertain when in Paris.

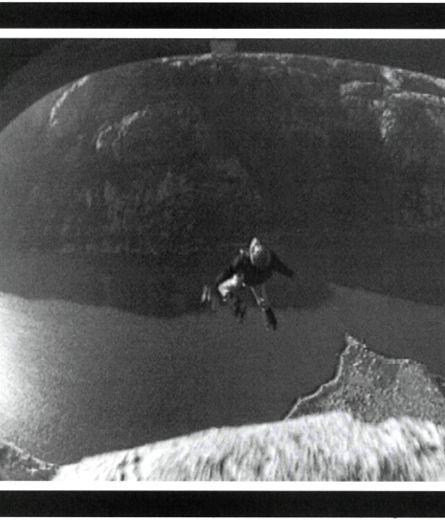

B.A.S.E. jumping is just about as gnarly as it gets. There only are four ways you leave the scene of jumps: in a getaway vehicle, the back of a police car, a life flight helicopter, or the coroner’s van. There are no injuries in this activity, no do-overs. It takes pure concentration and you have to know everything that could go wrong and be able to instinctively, reflexively do the right thing the instant the shit goes down. The second it takes to

think

about what to do next is the difference between life and death. Veterans say B.A.S.E. jumping is the most rewarding thing they’ve ever done, and they advise nobody to ever follow their footsteps. Overcoming the risks, stepping up to the challenge, and experiencing the reward of controlling an out-of-control situation—where do I sign up?