The Road to Freedom (13 page)

Read The Road to Freedom Online

Authors: Arthur C. Brooks

Woodrow Wilson had a statist philosophy that today sounds quite academic; indeed, he held a PhD in political science and taught at Princeton years before his tenure in the White House. In 1887 he published the essay “Socialism and Democracy,” in which he stated, “Men as communities are supreme over men as individuals. Limits of wisdom and convenience to the public control there may be: limits of principle there are, upon strict analysis, none.”

7

Clearing away the rhetorical clutter in the last sentence, Wilson was asserting that there was

no

moral claim for limited government. This is why he believed there was no inherent moral difference between democracy and socialismâand what led to his belief in bureaucracy as a science.

8

After he was elected president, Wilson sought to change the relationship of Americans to their government. His expansion of the state was massive. He created the Federal Reserve and agencies such as the Federal Trade Commission, increasing the size of government by almost 171 percent from 1913 to 1921, even after the buildup for World War I had ended and the war expenses had ceased.

9

Wilson's efforts to increase the size and scope of government were carried forward a few decades later by Franklin D. Roosevelt. FDR met the Great Depression with government growthâ“stimulus,” in today's parlance. He created dozens of government agencies, from the Federal Housing Administration to the National Labor Relations Board, increasing the size of the federal government by 90 percent in the first eight years of his presidency (prior to America's entry into World War II).

10

You probably learned in school that New Deal government programs were terrific for the American economy: They ended the worst period of unemployment in American history. But, what you learned is not true. Roosevelt's policies were

not

good for the economy. A 1935 study by the Brookings Institution, for example,

examined the accomplishments of Roosevelt's National Recovery Administration (NRA), which regulated working conditions. According to the Brookings study, the NRA “on the whole retarded recovery.”

11

In her bestselling book

The Forgotten Man

, economic historian Amity Shlaes shows that Roosevelt's spending heaped massive burdens on the country that more than offset the benefits of New Deal programs.

12

Shlaes argues that federal intervention helped prolong the Great Depression and made it deeper than it would otherwise have been. But government works like a ratchet, and government activity levels effectively never fell from their New Deal highs.

Lyndon B. Johnson picked up where FDR had left off in making the government central in the lives of millions of Americans. In his five years in office, Johnson increased the size of the federal government by 30 percent, but much more importantly, started a tidal wave of entitlements that inflated the size of government for many years after he left office. Johnson's legacy accomplishment was a set of programs collectively known as the Great Society, which dealt with education, medical care, urban problems, and transportation. The most ambitious part of it was known as the War on Poverty, which started programs from Head Start to food stamps.

Critics say generations of Americans were alienated from the workforce as a result of Johnson's programs, whole classes defined themselves as claimants on the U.S. government, and millions were consigned to squalid government housing and dignity-stripping welfare programs. As Ronald Reagan later quipped, “My friends, some years ago, the Federal Government declared war on poverty, and poverty won.”

13

But at the time, the benefits of the programs seemed plausible to millions of Americans. Some of the most damaging welfare programs (such as Aid to Families with Dependent Children, or AFDC) have been reformed or replaced, but other Great

Society entitlements such as Medicare and Medicaid have yet to be reformed, and today threaten the viability of the U.S. economy.

These eras of Wilson, Roosevelt, and Johnson were profligate indeed, as the data in the next section will show. But there is a broader point to absorb: No particular president (except perhaps Calvin Coolidge) since the beginning of the twentieth century is really blameless when it comes to the explosion in government activity. Some like Wilson, Roosevelt, and Johnson were especially enthusiastic proponents of government growth, and some like Ronald Reagan held the line a little more than others. But none reversed the trends. In general, the twentieth century was the bipartisan century of big government.

SOCIAL DEMOCRACIES

have been the norm in Western Europe since World War II. These systems are mildly utopianâbased on a philosophy that the government can improve its citizens. But fundamentally, these systems are practical. They are motivated by a popular will to achieve higher levels of comfort, and lower levels of personal risk. Social democracies dominate in low-fertility, aging societies that are less comfortable with risk than they once might have been.

While professing some reliance on market forces, social democracies always build a large welfare state. Citizens enjoy early retirement ages, short working hours, generous unemployment benefits, and various types of socialized medicine. In social democracies, taxes tend to be high to pay for the large state and are extremely progressive to lower economic inequality. Regulation is generally complex and onerous, to achieve social goals and curb excess profitmaking.

With some exceptions like Germany, social democracies spend more money than their tax revenues can generate, so a large and

increasing national debt is the norm. Economic growth is relatively low as the tax and regulatory systems leave entrepreneurs little incentive to innovate and work hard. In the long run, social democracies can produce dysfunctional governments and unstable economic and social situations like those in Spain, Greece, Portugal, and Italyâall of which are now being crushed under a burden of debt after years of profligate government spending but modest national output.

But America is different, right? Actually, no. Despite all the claims that America is organized on free market principles, over the decades it has become arguably just as socially democratic as Europe. Consider the following five facts.

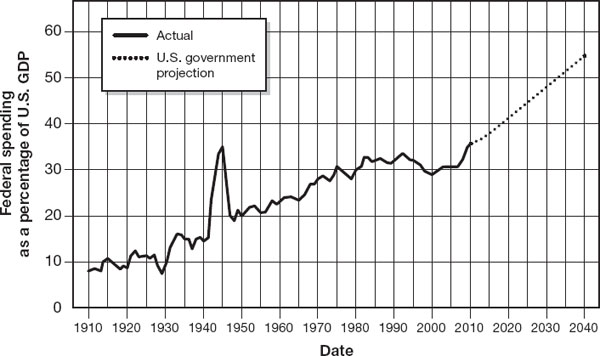

In 1913, after passage of the Sixteenth Amendment that created the federal income tax, total government spending at all levels was about 8 percent of GDP. By 2010 it had risen to 36 percent, and by 2038 it will be 50 percent.

14

Figure 5.1

is a graphic story of America's economic transformation. Ignore the World War I and World War II spending surges, and note only the broader trends. Big spending run-ups during the century never reverse, except for a brief period in the 1990s when the United States was disinvesting in its military. The increases are largely explained by massive entitlements, which politicians on both sides of the aisle have never meaningfully reined in.

The political right can crow all it wants about how America is a “conservative country,” unlike, say, Spainâa country governed by the Spanish Socialist Workers Party for most of the past thirty years. But, according to OECD data, U.S. government spending relative to its GDP is approximately equal to Spain's.

15

Figure 5.1

. Government spending has risen massively as a percentage of American GDP. (Source: Author's calculations

.

16

)

Progressive taxation means that the more you earn, the higher

percentage

you pay in taxes. For example, if you earn $34,500 today, your federal income tax rate on the last dollar you earn is 15 percent. If you earn $380,000, your rate is 35 percent. Most Americans do not object very much to this basic system. According to a November 2011 NBC News/

Wall Street Journal

poll, 56 percent of Americans prefer a graduated income tax system, while 40 percent of people prefer a system in which everyone pays the same rate.

17

Even conservative “flat tax” proposals almost always stipulate that low earners pay lessâor even zero taxes.

Cutting the bottom out of the tax distribution has been a pronounced trend since the early 1990s, and it has silently exploded the progressivity of the American income tax system. While progressives have screamed that upper tax rates have not gotten more

progressive year after yearâthey have gone up and down over the decades for top earnersâthe percentage of Americans who don't pay income taxes has steadily risen.

In 1990, 21 percent of Americans paid no federal income taxes.

18

In 2009, it was 46 percent.

19

For nearly half of all households in America, federal government services, from the US Army to the space program, are

free

. In fact, more than half of nonpayers pay

less

than zero: 30 percent get a “refundable credit,” meaning they get a check from the government for more than they paid in.

20

Progressive tax rates at the top may not bother you, within reason. But having a lot of people with no skin in the game bothers most Americans a great deal. According to the Tax Foundation, 66 percent of Americans believe that everyone should be required to pay some amount of federal taxes.

21

This leads to an even more troubling social democratic fact: Most Americans are on a form of welfare. The majority of Americans today consume more in government services than they pay for in taxes. When George W. Bush left office, this percentage was 60 percent. Today, it is headed toward 70 percent as various parts of President Obama's social agenda are enacted.

22

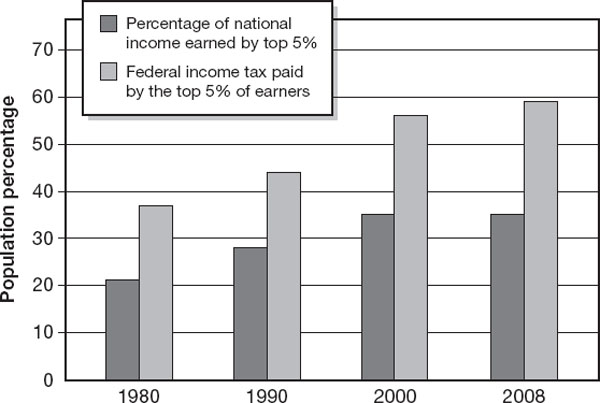

Progressive leaders often complain that America's income distribution is lopsidedâfor example, that the top 5 percent of earners in America earn 35 percent of total national income. Yes, but they pay 59 percent of all the federal income taxes.

23

That is to say, their tax share is 69 percent larger than their income share.

Of course, income tax is only one part of the full tax burden Americans bear. But even if the taxes that the poor

do

pay, like payroll and excise taxes, are added in, the story is essentially unchanged. According to the CBO, adding together all federal taxes, the bottom quintile of Americans paid 4 percent of their income in taxes in 2007. Meanwhile the top 5 percent paid 28 percent of their income in federal taxes.

24

These large differences are explained by the high percentage of nonpayers.

Figure 5.2

. The government is loading a higher and higher percentage of the tax bill on fewer and fewer people. (Source: Gerand Prante and Mark Robyn, “Summary of Latest Federal Individual Income Tax Data,” Tax Foundation Fiscal Facts, October 6, 2010,

http://www.taxfoundation.org/news/show/250.html

.)

Social democrats believe this is right and just because progressive taxation redistributes money and services in a way that lowers income inequality. The rest of Americans should see this as a huge problem. America simply cannot expect to maintain a responsible citizenry when half of its citizens don't pay for key public services such as the national defense.

25

A

MERICAN BUSINESS ARE HEAVY BY WORLD STANDARDS, AND GROWING

In social democracies, the government tends to penalize productive activity to raise revenues and achieve social goals. It does so by taking a relatively large share of private sector business revenues

in taxes, and raising the cost of production through regulation. Both of these phenomena have cropped up in the United Statesâespecially in the past few decades.