The Road to Freedom (9 page)

Read The Road to Freedom Online

Authors: Arthur C. Brooks

I reject any argument that bureaucrats are fairer than markets. There is nothing fair about corporate welfare and bailouts, or pork-barrel government spending. Fairness has nothing to do with the billions of dollars to save General Motors and Chrysler from bankruptcy. It has nothing to do with the stimulus spending of the past three years.

Finally, there is something radically depressing about the logic of redistributive fairness. Those who believe in it assume that simply by writing a check to increase someone's buying power, the recipient will have a more fulfilling life. Notice that its proponents speak only rarely about inequality in the things that matter most to people, the institutions of meaning in life, like faith, charity, and happiness. They speak about the money.

A MORAL SYSTEM

requires fairness. A fair system in an opportunity society rewards merit. In contrast, an

un

fair system redistributes resources simply to derive greater income equality. That is a world

in which, in the words of Rudyard Kipling, “all men are paid for existing and no man must pay for his sins.”

38

America does not have a perfect opportunity society. But if we want to move closer to that ideal, we must define fairness as meritocracy, embrace an economic system that rewards merit, and work tirelessly for more equal opportunity for all, rich and poor alike.

The system that makes all this possible, of course, is free enterprise. When I work harder or longer hours in the free enterprise system, I am generally paid more than if I work less in the same job. Investments in my education translate into market rewards. Clever ideas usually garner more rewards than bad ones, as judged not by a politburo, but rather by large groups of citizens in the marketplace. True fairness makes free enterprise not just an economic alternative. It makes it a moral imperative.

I want to emphasize two things that I am

not

arguing.

First, I am not arguing for anything like corporate cronyism. I believe in the free enterprise system; I do not believe in the unjust allocation of rewards to anyone, rich or poor. I am wholly opposed to the corporate bailouts in 2008 and 2009, just as I am opposed to government subsidies for energy companies and tax loopholes to favored industries. Corporate cronyism, like statism, is just another way to wreck competition and freedom. Further, lurking behind almost every case of uncompetitive business practices are perpetrators who have a close relationship with government power.

Second, I am not arguing that there is no role for government in this system. Private markets can and do fail, and the state may have a responsibility to act in some of these cases. Most serious economists also believe that a social safety net in a civilized country is appropriate to prevent the worst predations of poverty. When the government focuses on these things, it assists the free

enterprise system. But when the government bails out companies suffering from poor business practices or redistributes goods, services, and income simply for the sake of “fairness,” it lowers opportunity and impoverishes people in many ways.

Still, you might be asking, “What about the poor?” Distributing income according to merit might be good and just, but we all recognize that some people won't be able to take care of themselves properly. Fair or not, we want to help with more than just a minimum government safety net.

This brings us to the third moral promise of the free enterprise system and arguably its greatest achievement, helping the poor all around the world.

A S

YSTEM FOR

G

OOD

S

AMARITANS

O

ne of the most famous parables in the Christian Bible is the story of the Good Samaritan.

1

Jesus was asked by a follower, “Who is my neighbor?” In response, Jesus told the story of a Jew traveling along the road from Jerusalem to Jericho. The man was attacked by thieves, who robbed him and left him stripped and beaten. As he lay there half dead, two Jewish religious leadersâa priest and a Leviteâfound him on the road. Instead of helping the man, they passed on the other side. After them came a Samaritan, who, seeing the man, had compassion and stopped to help. Despite many years of hatred between Samaritans and Jews, the Samaritan bound up the injured man's wounds, fed him, clothed him, and took him to an inn. Before departing, the Good Samaritan left money and instructions for the innkeeper to ensure that the man was cared for.

The point of the parable is clear: People have a duty to help those in needânot only those close to them, but also strangers and

even enemies. Preoccupation with our own affairs is no excuse for ignoring the vulnerable. No matter what your religious beliefs, you probably agree with this, which is why everyoneâChristian, Muslim, Jew, atheist, whateverâknows what a “Good Samaritan” is and believes there should be more of them.

Today, many believe that political progressives are the Good Samaritans because they support government welfare programs that help the poor. During the heated federal budget battles of 2011, one liberal Christian group took out full-page ads in a national newspaper with the provocative question, “What Would Jesus Cut?”

2

The ad asked readers to sign a petition asking Congress to oppose any policies that involved cutting domestic and international programs that benefit the poor, especially children.

In this construction, of course, proponents of limited government and the free enterprise system are the priest and the Levite who just walk by as the poor and needy suffer. Capitalism creates incentives for people to be greedy and selfish, and to pursue their own economic interests regardless of the damage they cause. This may even be too charitable: Many argue that free marketeers are like the

robbers

. Free enterprise helps the rich get richer at the expense of the poor. Capitalism doesn't just allow people to ignore the injured man in the ditch; the system throws him in and then makes people ever more likely to be unmoved by his plight.

Supporters of the welfare state thus levy two related moral charges against free enterprise. The first is that it makes the rich richer and doesn't help the poor. The second is that it is morally corrupting; it makes people indifferent to the suffering of others.

The first charge is the easiest to debunk. While free enterprise may create significant income inequality, it actually helps

everyone

. True, the rich may get very rich in a free market economy, but the

poor get much richer too. As Senator Marco Rubio of Florida has remarked, “the free enterprise system has lifted more people out of poverty than all the government anti-poverty programs combined.”

3

The evidence shows that the senator is correct.

The second charge is more interesting. Certainly, the economic collapse has exposed plenty of villainsâfrom bailed out Wall Street CEOs with gold-plated exit packages to criminals like Bernie Madoffâwhom progressives love to point to as examples of the moral turpitude of unfettered capitalism. But those are just easy potshotsâcrooks and corporate cronies are not part of a healthy free enterprise system. I will show that America's everyday capitalistsâthe millions who work honestly and support free enterprise over government redistributionâare the real Good Samaritans in society.

FREE ENTERPRISE

has made life better today than at any time in history.

Economic historians have established that in 1800, the average person had a standard of living no better than people living in the Stone Age.

4

Of course, some people were better off than others. A handful of the world's population in 1800 were rich (by the standards of the day) and lived in relative splendor, but the masses did not eat better, sleep more comfortably, clothe themselves more warmly, or shelter themselves from the elements more snugly than their ancestors did 100,000 years earlier.

Life in 1800 was incomparably worse than it is today in every physical way: shorter, more dangerous, and filled with sickness. In the mid-eighteenth century, even in the world's most advanced cities like London, only one-quarter of the population could expect to live beyond five years of age.

5

For the lucky few who made it out of childhood in the eighteenth century, the life that awaited them was difficult and short. According to one historian of the period, “violence, disorder, and brutal punishment were a part of the normal background of life.”

6

Disease was rampant and food was short. In the great cities of London and Paris, “plague, disease, or famine would strike every decade or so, killing as many as 10,000 people in a few weeks.”

7

Modern Americans tend to take for granted that our lives will become more prosperous as we age, and that our kids will enjoy even better lives than we do. And for good reason: The average American enjoys 35 percent more real income today than thirty years ago, and every income bracket has benefited.

8

Americans think that material progress is, if not the natural order of things, at least a natural right. But this faith in economic progress is a new phenomenon, historically. Before 1800, children could not expect a better life than their parents, grandparents, or any ancestors, for that matter. World GDP per capita actually fell slightly from AD 1 to AD 1000, and grew just 47 percent from 1000 to 1820.

9

So for all of history until about 200 years ago, the world was desperately poor. But then something happened: the Industrial Revolution, and what economist Gregory Clark has termed the “Great Divergence.” In one set of countries, average prosperity in the 19th century began to rocket upward. In these lucky countries, income, standard of living, health, literacyâin short, every measurable aspect of well-beingâsaw a dramatic increase, unparalleled in history. In the unlucky countries left behind by the Industrial Revolutionâthe rest of the worldâincomes and quality of life stayed more or less where they had been for centuries.

America was one of the lucky countries. The explosion in better living standards can be illustrated with a handful of statistics.

In 1850, life expectancy at birth in the United States was 38.3.

10

By 2010, it was 78.

11

The literacy rate in the United States rose from 80 percent in 1870 to 99 percent today.

12

And real per capita GDP increased twenty-two-fold from 1820 to 1998.

13

The primary beneficiaries of the Industrial Revolution were the poorest members of society, not the richest. It is easy to think of the misery portrayed in Charles Dickens' novels and imagine that the Industrial Revolution had made life worse for people who might have happily lived an agrarian life. In truth, after the early 1800s, living standards for the poorest Americans and Europeans began to rise to levels unimaginable a few years earlier. Until the Industrial Revolution, for example, formal education was reserved for the wealthy who could afford to pay and who could afford to keep their children out of the workforce. There was no education for the poor in America until the first public school opened in Boston in 1817. With the Industrial Revolution, public schools quickly spread to educate the masses. Within a century from the construction of the first public school, laws mandated primary education in most of the United States, and 72 percent of children had completed grade school.

14

To be sure, there was much progress still to be made, and during the Industrial Revolution, life for the working class was hard. But compared to what had come before, the Industrial Revolution's accompanying economic and social benefits were the greatest antipoverty program ever known.

15

After more than a century, the Industrial Revolution's blessings ultimately began to spread beyond Europe and America. As the twentieth century progressed, the number of lucky countries around the world grew. As a result, global poverty is decreasing radically, with real world GDP per capita today many times larger than it was in 1820.

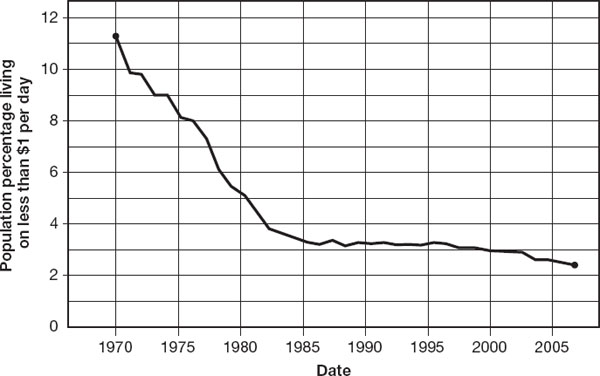

Figure 4.1

. The percentage of the world's population living on less than $1 per day has fallen dramatically. (Source: Maxim Pinkovskiy and Xavier Sala-i-Martin, “Parametric Estimations of the world distribution of income,” NBER Working Paper 15433,

http://www.nber.org/papers/w15433.pdf

.)

The improvements have been massive even in recent decades. The number of people in the world living on a dollar a dayâa traditional poverty measureâhas fallen by 80 percent since 1970, from 11.2 percent of the world's population to 2.3 percent.

16