The Road to Little Dribbling (9 page)

Read The Road to Little Dribbling Online

Authors: Bill Bryson

Now I am not saying that London is the world’s best city because it had a homosexual brothel scandal or because Virginia Woolf and L. Ron Hubbard lived around the corner, or anything like that. I am just saying that London is layered with history and full of secret corners in a way that no other city can touch. And it has pubs and lots of trees and is often quite lovely. You can’t beat that.

—

My two dear, pregnant daughters live in separate parts of London—Putney and Thames Ditton—about ten miles apart, and I decided one day to walk from one to the other after I realized that you can do so almost entirely through parkland. West London is extraordinarily well endowed with open spaces. Putney Heath and Wimbledon Common cover 1,430 acres between them. Richmond Park has 2,500 acres more, Bushy Park 1,100 acres, Hampton Court Park 750 acres, Ham Common 120 acres, Kew Gardens 300 more. Looked at from above, west London isn’t so much a city as a forest with buildings.

I had never been on Putney Heath or Wimbledon Common—they run seamlessly together—and they were splendid. They were not at all like the manicured parks I had grown used to in London, but were untended and rather wild, and all the more agreeable for that. I walked for some time over heath and through woods, never very sure where I was despite having an Ordnance Survey map. The farther I walked, the more isolated things felt.

At one point it occurred to me that I hadn’t seen anybody for about half an hour, couldn’t hear traffic, had no idea where I would be when I next saw civilization. I had set off with the vague thought of walking past the site of Dwight D. Eisenhower’s home during the Second World War, which I had by chance recently discovered lay more or less along the route I was taking today. I had read at the library about Eisenhower’s domestic arrangements during the war. He could have had a stately home like Syon House or Cliveden, but instead he chose to live alone without servants in a simple dwelling called Telegraph Cottage on the edge of Wimbledon Common. The house was up a long driveway, the entrance guarded by a single soldier standing beside a pole barrier. That was all the security the Supreme Allied Commander enjoyed. German assassins could have parachuted onto Wimbledon Common, entered Eisenhower’s property from the rear, and killed him in his bed. I think that’s rather wonderful—not that Germans could have done that, of course, but that they didn’t.

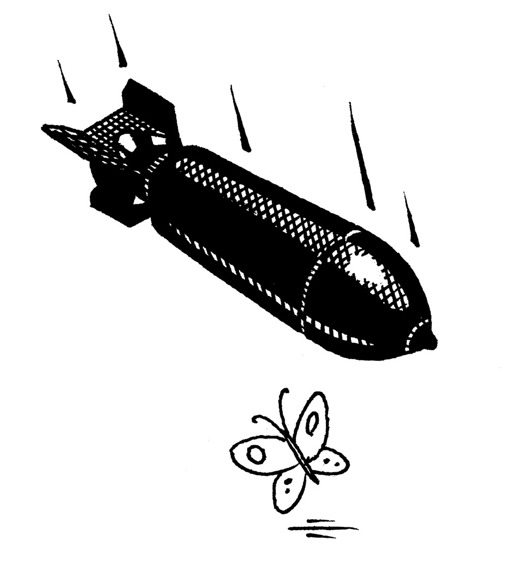

Although the Germans missed their chance to assassinate Eisenhower, they might easily have bombed him. Unbeknownst to Eisenhower or evidently anyone else on the Allied side, it seems, civil defense forces had erected a dummy anti-aircraft gun in a clearing just the other side of a hedge from Eisenhower’s cottage. Dummy guns were put up all around London in an effort to fool German reconnaissance and trick their planes into wasting bombs. Fortunately for Eisenhower, the Luftwaffe seem to have overlooked this one.

Bearing in mind that I was largely lost, you may imagine my delight when I emerged from the common through the grounds of a rugby club, and discovered that I had more or less blundered onto the site of Eisenhower’s cottage, though there is no telling the exact spot anymore. Telegraph Cottage burned down some years ago, and today the site is covered with houses, but I had a good stroll around and continued on to Thames Ditton satisfied that I had more or less hit my target, which is more than the Germans managed to do, thank goodness.

Buoyed up by my discovery, I carried on to Thames Ditton by way of Richmond Park and a long walk along the Thames. It was a very nice day. I had two weeks of very nice days and got to pretend it was work. That’s why I do this for a living.

—

Of course not everything is ideal in London. About twenty years ago, my wife and I bought a small flat in South Kensington. At the time it seemed the wildest extravagance, but now after two decades of property price inflation we look like financial geniuses. But the neighborhood has changed. The gutters are permanently adrift in litter, some of it dragged there by foxes that scavenge through garbage left out overnight, most of it left by people who have neither brains nor pride (nor any fear of punishment). Workmen for some years have been quietly painting the street white one bucket at a time. The most dismaying loss, I think, is of front gardens. People seem strangely intent on getting their cars as close to their living rooms as possible, and to that end have been ripping out their little front yards and replacing them with paved service areas so that there is always a place for their cars and garbage bins. I don’t quite understand why they are permitted to do this since nothing more obviously ruins a street. Not far from us is a street called Hurlingham Gardens, which should really be called Hurlingham Bin Storage Areas since nearly every owner has removed any trace of attractiveness from in front of their houses. The absence of any feeling of aesthetic obligation to one’s own street is perhaps the saddest change in Britain in my time there.

On the larger scale, however, things have improved enormously in London. In the space of twenty years or so, London has acquired a memorable skyline, for one thing. It isn’t that it has a huge number of tall buildings, but that the tall buildings it has are spread over a wide area. They don’t jostle for attention, as in most cities, but stand alone so that you can admire them in isolation, like giant pieces of sculpture. It’s a brilliant stroke. Now you get interesting views from all kinds of places—from Putney Bridge, from the Round Pond at Kensington Gardens, from platform 12 at Clapham Junction station—where there never used to be views at all. Scattered skyscrapers also have the incidental benefit of spreading prosperity. A new skyscraper in central London just adds more bodies to crowded streets and Underground stations, but a big new building in a more outlying area like Southwark or Lambeth or Nine Elms gives a jolt of economic input that can lift whole neighborhoods, creating demand for bars and restaurants, and making faded districts more desirable places to live or visit.

None of this was precisely intended. It is the by-product of something called the London Plan, which decrees that tall buildings may not impinge on protected views. One such view is from a certain oak tree on Hampstead Heath. (Well, why not?) No one can build anything that interrupts the view from the tree to St. Paul’s Cathedral or the Houses of Parliament. There is a similar view from Richmond Park, miles from the city—so far out that I didn’t even know you could see any of central London from there. London is crisscrossed by protected sightlines, which effectively requires tall buildings to be spaced out. It is a happy accident. But then that is London. It is centuries of happy accidents.

What is perhaps most extraordinary is how very nearly so much of it was lost. In the 1950s, Britain became obsessed with the idea that it needed to modernize, and that the way to do so was to tear down most of what the Germans hadn’t bombed and cover what remained under steel and concrete.

One after another through the 1950s and ’60s, grand plans were unveiled to bulldoze and rebuild great chunks of London. Piccadilly Circus, Covent Garden, Oxford Street, the Strand, Whitehall, and much of Soho all were proposed for redevelopment. Sloane Square was to be replaced with a shopping center and high-rise apartment building. The area from Westminster Abbey to Trafalgar Square would become a new government district, “a British Stalingrad of concrete and glass slabs,” in the words of one commentator. Four hundred miles of new motorways were to sweep through London and a thousand miles of existing roads, including Tottenham Court Road and the Strand, were to be widened and made faster—essentially turned into urban expressways—to tear through the heart of the city. Throughout central London pedestrians wishing to cross busy roads would be directed into tunnels or up onto metal or concrete footbridges. Walking through London would be like endlessly changing platforms at a mainline train station.

It all seems a kind of madness now, but there was remarkably little opposition. Colin Buchanan, Britain’s most influential planner, promised that sweeping away the accumulated clutter of centuries and building gleaming new cities of concrete and steel would “touch a chord of pride in the British people and help to give them that economic and spiritual lift of which they stand in need.” When a developer named Jack Cotton proposed to clear out most of Piccadilly Circus and build a 172-foot-high tower that looked like a cross between a transistor radio and a workman’s toolbox, the proposal received the blessing of the Royal Fine Art Commission and was passed without dissent at a secret meeting of the Westminster Council Planning Department. Under Cotton’s plan, the famous statue of Eros was to be raised up to a new pedestrian platform and integrated with a network of walkways and footbridges to keep people safely segregated from the speeding traffic below.

In 1973, the year I first settled in Britain, the most sweeping plan of all was unveiled: the Greater London Development Plan. This elaborated on all the earlier proposals and called for building a series of four orbital motorways, which would encircle the city like ripples on a pond, with twelve radial freeways bringing all the capital’s motorways (the British equivalent of US interstate highways) into the very heart of the city. Freeways, mostly elevated, would slice through practically every district of London—through Hammersmith, Fulham, Chelsea, Earls Court, Battersea, Barnes, Chiswick, Clapham, Lambeth, Islington, Camden Town, Hampstead, Belsize Park, Poplar, Hackney, Deptford, Wimbledon, Blackheath, Greenwich, and more. A hundred thousand people would lose their homes. Almost nowhere would be spared the roar of speeding traffic. Remarkably, many people couldn’t wait for this to happen. A writer for the

Illustrated London News

insisted that people “enjoyed being close to busy traffic” and cited the new Spaghetti Junction interchange in Birmingham as a place made lively and colorful by its infusion of speeding vehicles. He noted also the propensity of British people to picnic in lay-bys (small rest areas beside busy highways), which he interpreted as a fondness for “noise and bustle,” rather than the fact that they were just insane.

The Greater London Development Plan would have cost a then-colossal £2 billion, making it the biggest public investment ever made in Britain. That was its salvation. Britain couldn’t afford it. In the end, the visionaries were undone by the unmanageable scale of their own ambitions.

It is a mercy, of course, that none of these grand schemes ever saw life. But tucked in among them was one proposal that was quite different from all the others and might actually have been worth trying. It was called Motopia, and that is where I was headed next.

Chapter 5

Motopia

I

TOOK THE 8:28

from Waterloo to Wraysbury via many stations. It was the morning rush hour, but all the rushing was in the opposite direction. My train was pleasingly empty. British train interiors used to be heavy and gloomy in a way that perfectly suited the dull, cheerless, stolid business of commuting. Now trains are full of bright oranges and reds. This one was rather annoyingly festive, like a children’s fairground ride. I felt as if I should have had a toy steering wheel and little bell by my seat.

I was the only person to alight at Wraysbury station, which was unmanned and rather spookily deserted. The station stood a mile or so from the village, but it was a pleasant walk along a shady lane. Wraysbury is a strange, cut-off place. It is on the Thames opposite Runnymede and only a couple of miles from Windsor Castle as the crow flies, but it might as well be in Caithness for all its accessibility. It is separated from the outside world by an almost ludicrous number of barriers—two motorways, a railroad, acres of old gravel pits, an unbridged stretch of the Thames, three enormous reservoirs buttressed by hill-sized grassy banks and bounded by miles of high-security fences, and, finally, the great, impenetrable sprawl of Heathrow Airport and its service areas. The road approaches to Wraysbury are through zones largely filled with light industry, cement works, pumping stations, and other realms of heavy lorries and “Keep Out” signs. No one arrives in Wraysbury by accident and not many go there on purpose, but those who manage to pick their way through the surrounding dust and clutter find themselves in a sudden oasis of attractive tranquillity—or at least tranquil up to a height of about five hundred feet, for airplanes crowd the skies nearby as they begin and end their voyages at Heathrow.

But for those who can adjust to the noise above, Wraysbury is a sweet and agreeable place. The village has a church and a broad green with a cricket pavilion, a couple of good pubs, and a cluster of useful shops. The surrounding gravel pits have been filled with water to make recreational lakes, which are now the homes of many sailing and windsurfing clubs. Many of the houses are large and attractive, particularly where they overlook water. My wife grew up just across the Thames in Egham. From her side of the river, Wraysbury’s rooftops are visible among the trees. This much I had seen a thousand times, but I had never been there, never had a reason to go.