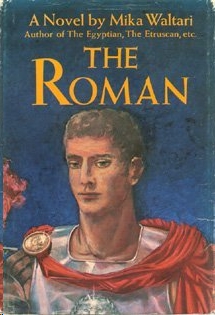

The Roman

THE ROMAN

The memoirs of Minutus Lausus Manilianus, who has won the Insignia of a Triumph, who has the rank of Consul, who is Chairman of the Priests� Collegium of the god Vespasian and a member of the Roman Senate by MIKA WALTARI

CONTENTS

PART ONE�MINUTUS

Book Page 1 Antioch 14 2 Rome 46 3 Britain 130 4 Claudia 168 5 Corinth 206 6 Sabina 254 7 Agrippina 296

PART TWO�JULIUS, MY SON

8 Poppaea 350 9 Tigellinus 398 10 The Witnesses 450 11 Antonia 488 12 The Informer 524 13 Nero 560 14 Vespasian 604 Epilogue 637

THE JULIAM HOUSE JULIUS CAESAR MARCIA JULIUS CAELSAR JULIAATIUS SALBUS ATIA C OCTAVIUS OCTAVIA AUGUSTA L C MARCELLUS 2. MARCUS ANTONIUS AUCUSTUS ESCRIBONIA 2. LIVIA (MOTHER OF TIBERIUS) ANRONIAMAJOR DOMITIUS AKENOBARBUS ANTONIA� MINOR= DRUSUS MAJOR JULIAA I. MARCELLUS 2.AGRIPPA .TIBERLUS I I DOMITIA LEPIDABARBERTUS DOMITIUS GERMANICUS CLAUDIUS � I URGURANILLA 3. MESSALINA AGRIPPINA CERMANICUS 2. AELIA 4. AGRIPPINA I I MESSALINA CLAUDIUIS ANTONIA ACRIPPINA=I.DOMITIUS 2.CLAUDIUS C CALIGULA OCTAVIA � NERO- BRITANHTCUS LUCIUS DOMITIUS NERO I. OCTAVIA 2. POPPAEA CLAUDIA AUGUSTA

PART ONE MINUTUS

Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, Claudius (25).

Because the Jews at Rome caused disturbances at the instigation of Christus [Claudius) banished them.

Aurelius Victor, De Caesoribus (5)

Although he held power for the same number of years as his stepfather, and for much of that time as a very young man, yet for the first five years he was so great, particularly in his development of the city, that Trajan used often to assert, and rightly, that none of the emperors came anywhere near matching those five years of Nero.

BOOK 1

Antioch

I WAS seven years old when the veteran Barbus saved my life. I remember well how I tricked my old nurse Sophronia into letting me go down to the banks of the river Orontes. The rapid swirling current attracted me and I leaned over the jetty to look at the bubbling water. Then Barbus approached me and asked in a friendly way: �Do you want to learn to swim, boy?� I replied that I did. He looked around, and grasping me by the back of my neck and the crotch, he flung me far out into the river. Then he let out a wild cry, calling on Hercules and the Roman Jupiter the Conqueror, and flinging his ragged cloak down on the jetty, he plunged into the water after me. People flocked to his cry. They all saw and unanimously testified to how Barbus, at the risk of his own life, saved me from drowning, carried me ashore, and rolled me on the ground to make me spew up the water I had swallowed. When Sophronia arrived, crying and tearing her hair, Barbus lifted me in his strong arms and carried me all the way home, although I struggled to get away from his filthy clothes and the smell of wine on his breath. My father was not particularly fond of me, but he plied Barbus with wine and accepted his explanation that I had slipped and fallen into the water. I did not contradict Barbus, for I was used to holding my tongue in my father�s presence. On the contrary, I listened as if spellbound as Barbus modestly related how, during his time as a legionary, he had swum fully equipped across the Danube, the Rhine and even the Euphrates. My father drank wine, too, to calm his fears, and was himself disposed to relate how, as a youth at the school of philosophy in Rhodes, he had wagered that he could swim from Rhodes to the mainland. He and Barbus were in complete agreement that it was high time I

14

learned to swim, My father gave Barbus some new clothes so that when he was dressing, Barbus had an opportunity to exhibit his many scars. From that time onwards Barbus stayed at our house and called my father master. He escorted me to school, and when he was not too drunk, came to fetch me at the end of the school day. First and foremost, he raised me as a Roman, for he really had been born and bred in Rome and had served for thirty years in the 15th legion. My father was careful to confirm this, for although he was an absentminded and reserved man, he was not stupid and would never have employed a deserter in his house. Thanks to Barbus, I learned not only to swim but also to ride. At his request my father bought me a horse of my own so that I could become a member of the young Equestrian Knights in Antioch as soon as I was fourteen. It was true that Emperor Gaius Caligula had struck my father�s name from the rolls of the Roman Noble Order of Equestrian Knights with his own hand, but in Antioch that was considered more of an honor than a disgrace since everyone remembered only too well what a good-for-nothing Caligula had been, even as a youth. Later he was murdered at the great circus in Rome as he was about to promote his favorite horse to the rank of Senator. At the time, my father, albeit reluctantly, had reached such a position in Antioch that they wanted him to go with the delegation the city was sending to Rome to congratulate Emperor Claudius on his accession. His knighthood would undoubtedly have been returned to him there, but my father resolutely refused to go to Rome, and later it was proved that he had had good reasons for this. Now he himself said that he preferred to live in peace and humility and that he had no desire for a knighthood. Just as Barbus had come to our house by chance, so also had my father�s fortune increased. He used to say in his bitter way that he had had no luck in his life, for when I was born, he lost the only woman he had ever really loved. But even in Damascus he had already made a habit of going to the market on the anniversary of my mother�s death and buying a wretched slave or two. Then when my father had kept the slave for a time and fed him well, he took him to the authorities, paid the redemption fee and gave the slave his freedom. He allowed these freedmen to

15

use the name Marcius, not Manlianus, and gave them money so that they could begin to practice the trade they had learned. One of his freedmen became Marcius the silk merchant, another Marcius the fisherman, while Marcius the barber earned a fortune modernizing women�s wigs. But the one who became the wealthiest of all was Marcius the mine owner, who later made my father buy a copper mine in Sicily. My father also frequently complained that he could never carry out the smallest charitable deed without receiving benefit or praise from it. Since he had settled in Antioch, after his seven years in Damascus, he had served, good linguist and moderate that he was, as adviser to the Proconsul, especially on matters concerning Jewish affairs, in which he had become thoroughly versed during earlier travels in Judaea and Galilee. He was a mild and good- natured man and always recommended a compromise in preference to forceful measures. In this way he won the appreciation of the citizens of Antioch. After losing his knighthood, he was elected to the city council, not just for his strength of will and energy, but because each party thought he would be useful to them. When Caligula demanded that an idol of himself should be raised in the temple in Jerusalem and in all the synagogues in the province, my father realized that such an act would lead to armed uprising, and he advised the Jews to try to gain time rather than make unnecessary protests. So it came about that the Jews in Antioch let the Roman Senate think that they themselves wanted to pay for sufficiently worthy statues of the Emperor Gaius in their synagogues. But the statues suffered several misfortunes during their manufacture, or else the premonitory omens were unfavorable and prevented their erection. When Emperor Gaius was murdered, my father won much approval for his foresight. Though I do not believe he could have known anything about the murder beforehand but had merely wished, as usual, to gain time and avoid trouble with the Jews, which would have upset trade in the city. But my father could also be stubborn. As a member of the city council, he flatly refused to pay for circus shows of wild animals and gladiators and was even against theatrical performances. On the advice of his freedmen, however, he had an arcade

16

bearing his name built in the city. From the shops inside, he received considerable sums in rents so that the enterprise was also to his advantage, quite apart from the honor. My father�s freedmen could not understand why he dealt with me so severely, wishing me to be content with his own simple way of life. They competed to offer me all the money I might need, gave me beautiful clothes, had my saddle and harness decorated, and did their best to cover up for me, hiding my thoughtless deeds from him. Young and foolish as I was, I was tormented with a desire to be in all things as outstanding, or preferably even more outstanding, than the noble youths of the city, and my father�s freedmen shortsightedly considered that this would be to the advantage of both themselves and my father. Thanks to Barbus, my father realized it was necessary for me to learn Latin. Barbus�s own legionary Latin did not go very far. My father thus saw to it that I read the history books by Virgil and Livy. For evenings on end Barbus told me of the hills, sights and traditions of Rome, its gods and warriors, so that I was finally seized with a wild desire to go there. I was no Syrian, but had been born a Roman of Manilian and Maecenean lineage, even if my mother had been only a Greek. Naturally I did not neglect my Greek studies either, but at fifteen years of age already knew many of the poets. For two years I had Timaius from Rhodes as my tutor. My father had bought him after the disturbances in Rhodes and would have freed him, but Timaius bitterly refused each time, explaining that there was no real difference between slaves and freedmen, and that freedom lay in a man�s heart. So I was taught the Stoic philosophy by an embittered Timaius who despised my Latin studies, since Romans in his opinion were barbarians, and bore a grudge against Rome, which had deprived Rhodes of its freedom. Among the youth of the city who took part in the equestrian games were ten or so who vied with each other at wild exploits. We had sworn allegiance and had a tree to which we made sacrifices. On the way home from riding practice, we once recklessly decided to ride through the city at a gallop, and while doing so, to snatch the wreaths hanging on the shop doors. By mistake I grabbed one of the black oak-leaf wreaths which were hung as a sign that someone in the house had died, although we had meant

17

to do no more than annoy the shopkeepers. I should have realized that this was an ill omen, and inwardly I was frightened, but despite this I hung the wreath on our sacrificial tree. Everyone who knows Antioch will realize what a commotion our exploit caused, but naturally the police did not succeed in proving us guilty. We ourselves were forced to admit our guilt, for otherwise all the partakers in the equestrian games would have been punished. We escaped with fines since the magistrates did not want to offend our parents. After that we contented ourselves with exploits outside the city walls. Down by the river we once saw a group of girls busy doing something which roused our curiosity. We thought they were country girls, and I hit upon the idea of pretending to carry them off, just as the ancient Romans had seized the Sabine women. I told my friends the story of the Sabines and it amused them very much. So we rode down to the river and each of us seized the girl who happened to be in his way and lifted her onto the saddle in front of him. This was in fact easier said than done and it was equally difficult keeping the screaming, kicking girls there. In actual fact I did not know what to do with my girl, but I tickled her to make her laugh and when I had, as I thought, shown her sufficiently clearly that she was completely in my power, I rode back and let her down to the ground. My friends did the same. As we rode away, the girls threw stones at us and we were gripped with evil presentiments, for as I had held the girl in my arms, I had indeed noticed that she was no peasant girl. In fact they were all girls from noble families who had gone down to the river to purify themselves and make certain sacrifices which their new degree of womanhood demanded of them. We should have known this from the colored ribbons hanging on the bushes as a warning to outsiders. But which of us was versed in the mysterious rites of young girls? The girls might have kept the matter secret for their own sakes, but they had a priestess with them and her sense of duty drove her to think that we had deliberately committed blasphemy. So my idea led to a fearful scandal. It was even suggested that we ought to marry the girls whose virtue we had dishonored at a delicate moment of sacrifice. Fortunately none of us had yet received the man-toga.

18

My tutor, Timaius, was so angry that he hit me with a stick although he was a slave. Barbus tore the stick from his hand and advised me to flee from the city. Superstitious as he was, he also feared the Syrian gods. Timaius feared no gods since he saw all gods as nothing but idols, but he considered that my behavior had brought shame on him as a tutor. The worst was that it was impossible to keep the matter secret from my father. I was inexperienced and sensitive, and when I saw the fear in all the others, I myself began to think that our exploit had been more serious than it in fact was. Timaius, who was an old man and also a Stoic, ought to have been more balanced and encouraged me in the face of such trials rather than depressing me. But he revealed his true nature and all his bitterness when he said: �Who do you think you are, you idle, repulsive braggart? It was not without reason that your father gave you the name of Minutus, the insignificant one. Your mother was no more than a wanton Greek, a dancing-woman and worse, perhaps a slave. That�s your descent. It was according to the laws and no whim of Emperor Gaius that your father was struck from the rolls of knights, for he was expelled from Judaea in the time of Governor Pontius Pilate because he was involved in Jewish superstitions. He is no true Manilianus, only an adoptive one, and in Rome he made a fortune with the help of a shameful will. Then he was involved in a scandal with a married woman and can never again return there. So you are nothing, and you will become even more insignificant, you dissolute son of a miserly father.� He would undoubtedly have said even more had I not hit him across the mouth. I was immediately horrified at what I had done, for it is not correct for a pupil to hit his tutor, even if he is a slave. Timaius wiped the blood from his lips and smiled malevolently. �Thank you, Minutus my son, for this sign,� he said. �What is (looked can never grow straight and what is base can never be noble. You ought also to know that your father drinks blood in secret with the Jews and worships the goblet of the Goddess of Fortune secretly in his room. How else could anyone have been so successful and become so rich with no merits of his own? But I have already had enough of him, and of you, and of the whole of this unhappy world in which injustice reigns over justice, and wisdom has to sit by the door while insolence holds a feast.�