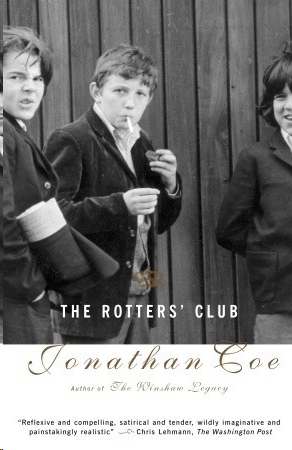

The Rotters' Club

Authors: Jonathan Coe

PENGUIN BOOKS

THE ROTTERS’ CLUB

‘Wonderfully entertaining… countless laugh-out-loud moments… an

unremittingly enjoyable reading experience’

Birmingham Post

‘Jonathan Coe is the most excition young British novelist writing

today and

The Rotters’ Club

is yet another in an unbroken string

of entrancing achievements’ Bret Easton Ellis

‘Confirms Jonathan Coe as one of our most compelling storytellers’

Daily Telegraph

, Books of the Year

‘Moving and very funny. A deeply truthful book’

Observer

, Books of the Year

‘At once uproariously entertaining and deadly serious–a conscientious

and politically charged reminder of an age quite easily forgotten, yet

not far removed form our own’

The Times Literary Suplement

‘superior entertainment. Vastly enjoyable’

New Statesman

‘Coe brilliantly captures all the existential angst of adolescence: its

mixture of dreamy romanticism and bitter rivalry; intellectual curiosity

and bewildered libidos; rebellious posturing and its oh-so-earnest

rhetoric. He is the only writer to possess the wit, vitality and

courage to address the most elusive topic of all – the burlesque

tragedies and grotesque comedies of the country in which we live’

Daily Express

‘A cracking evocation of the 1970s’

Daily Telegraph

‘Richly entertaining and Wonderfully achieved. A must read for anyone

who cares about contemporary literature’

Sunday Telegraph

‘Hooks you from the start… a hilarious ride through the whirligig

of the Seventies, and should be devoured in one sitting. Coe has a fine

ear for dialogue and the novel is packed with comic set pieces…

A triumph’

Literary Review

‘A vivid picture of this crooked, exhilaration, hopeful age… Coe

evokes the times effortlessly, never putting a foot wrong. A vibrant.

compulsively readable, deeply felt novel with moments of glory’

Sunday Herald

‘Does for the 1970s what his higly successful novel

What a Carve Up!

did for the 178s… Simultaneously satirical, extremely funny, and

literary… a writer of fine intelligence and humanity’

Financial Times

‘A tremendous romp through the bizarre, often very funny culture of

that troubled decade; the clothes, the music, the hair… The social

details are described by Coe with an accuracy and love that could make

you doubt his sanity, but never his vrilliance or his sense of humour…

A joy to read’

Spectator

‘Brilliant, funny, apposite, informed and unflaggingly truth-seeking’

Evening Standard

‘Coe is a screamingly funny writer at times, but he combines his

humour with pathos and thus gives his characters an astonishing clarity

and depht’

Scotland on Sunday

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jonathan Coe was born in Birmingham in 1961. His most recent novel is

The Rain Before It Falls.

He is also the author of

The Accidental Woman, A Touch of Love, The Dwarves of Death, What a Carve Up!

which won the 1995 John Lewellyn Rhys Prize, The House of sleep, Which won The 1998 Prix Medicis Etranger, The Rotters’ Club, winner of the Everyman Wodehouse Prize, and

The Closed Circle.

His biography of the novelist B.S. Johnson, Like a Fiery Elephant, won the 2005 Samuel Johnson Prize for best non-fiction book of the year. He lives in London With his wife and two children.

The Rotters' Club

JONATHAN COE

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd,80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc. 375 Hudson Street, New York 10014, USA

PENGUIN Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue Eest, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3

(adivision of Pearson Penguin Canada inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Lreland (a division of penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Books (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd. 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi – 110017, India

Penguin Group (NZ),67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue,

Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Redgistered offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

www.penguin.com

First published by Viking 2001

first published in Penguin Books 2002

This edition published 2008

1

Copyright © Jonathan Coe, 2001

lllustration coe, 2001

All rights reserved

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Except in the United States of America, theis book is sold subject

to the condintion that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent,

re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s

prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in

which it is published and without a similar condition including this

condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

978-0-14-191004-8

For Janine, Matilda and Madeline

On a clear, blueblack, starry night, in the city of Berlin, in the year 2003, two young people sat down to dinner. Their names were Sophie and Patrick.

These two people had never met, before today. Sophie was visiting Berlin with her mother, and Patrick was visiting with his father. Sophie’s mother and Patrick’s father had once known each other, very slightly, a long time ago. For a short while, Patrick’s father had even been infatuated with Sophie’s mother, when they were still at school. But it was twenty-nine years since they had last exchanged any words.

– Where do you think they’ve gone? Sophie asked.

– Clubbing, probably. Checking out the techno places.

– Are you serious?

– Of course not. My dad’s never been to a club in his life. The last album he bought was by Barclay James Harvest.

– Who?

– Exactly.

Sophie and Patrick watched as the vast, brightly lit glass-and-concrete extravagance of the new Reichstag came into view. The restaurant they had chosen, at the top of the Fernsehturm above Alexanderplatz, revolved rather more quickly than either of them had been expecting. Apparently the speed had been doubled since reunification.

– How is your mother now? Patrick asked. Has she recovered?

– Oh, that was nothing. We went back to the hotel, and she lay down for a while. After that, she was fine. Another couple of hours and we went shopping. That’s when I got this skirt.

– It looks great on you.

– Anyway, I’m glad that it happened, because otherwise your dad wouldn’t have recognized her.

– I suppose not.

– So we wouldn’t be sitting here, would we? It must be fate. Or something.

It was an odd situation they had been thrown into. There had seemed to be a spontaneous intimacy between their parents, even though it was so long since they had known each other. They had flung themselves into their reunion with a sort of joyous relief, as if this chance encounter in a Berlin tea-room could somehow erase the intervening decades, heal the pain of their passing. That had left Sophie and Patrick floundering in a different, more awkward kind of intimacy. They had nothing in common, they realized, except their parents’ histories.

– Does your father ever talk much about his schooldays? Sophie asked.

– Well, it’s funny. He never used to. But I think it’s all been coming back to him, lately. Some of the people he knew back then have resurfaced. For instance, there was a boy called…

– Harding?

– Yes. You know about him?

– A little. I’d like to know more.

– Then I’ll tell you. And Dad mentions your uncle sometimes. Your uncle Benjamin.

– Ah, yes. They were good friends, weren’t they?

– Best friends, I think.

– Did you know they once played in a band together?

– No, he never mentioned that.

– What about the magazine they used to edit?

– No, he never told me about that either.

– I’ve heard it all from my mother, you see. She has perfect recall of those days.

– How come?

– Well…

And then Sophie began to explain. It was hard to know where to start. The era they were discussing seemed to belong to the dimmest recesses of history. She said to Patrick:

– Do you ever try to imagine what it was like before you were born?

– How do you mean? You mean like in the womb?

– No, I mean, what the world was like, before you came along.

– Not really. I can’t get my head around it.

– But you remember how things were when you were younger. You remember John Major, for instance?

– Vaguely.

– Well, of course, that’s the only way to remember him. What about Mrs Thatcher?

– No. I was only… five or six when she resigned. Why are you asking this, anyway?

– Because we’re going to have to think further back than that. Much further.

Sophie broke off, and a frown darkened her face.

– You know, I can tell you this story, but you might get frustrated. It doesn’t end. It just stops. I don’t know how it ends.

– Perhaps I know the ending.

– Will you tell me, if you do?

– Of course.

They smiled at each other then, quickly and for the first time. As the crane-filled skyline, the ever-changing work-in-progress that was the Berlin cityscape unfurled behind her, Patrick looked at Sophie’s face, her graceful jaw, her long black eyelashes, and felt the stirrings of something, a thankfulness that he had met her, a flicker of curiosity about what his future might suddenly hold.

Sophie poured sparkling mineral water into her glass from a navy-blue bottle and said:

– Come with me, then, Patrick. Let’s go backwards. Backwards in time, all the way back to the beginning. Back to a country that neither of us would recognize, probably. Britain, 1973.

– Was it really that different, do you think?

– Completely different. Just think of it! A world without mobiles or videos or Playstations or even faxes. A world that had never heard of Princess Diana or Tony Blair, never thought for a moment of going to war in Kosovo or Afghanistan. There were only three television channels in those days, Patrick. Three! And the unions were so powerful that, if they wanted to, they could close one of them down for a whole night. Sometimes people even had to do without electricity. Imagine!

The Chick and the Hairy Guy

WINTER

1

Imagine!

November the 15th, 1973. A Thursday evening, drizzle whispering against the window-panes, and the family gathered in the living room. All except Colin, who is out on business, and has told his wife and children not to wait up. Weak light from a pair of wrought-iron standard lamps. The coal-effect fire hisses.

Sheila Trotter is reading the

Daily Mail: ‘“To have and to hold, for better for worse, for richer for poorer, in sickness and in health” – these are the promises which do in fact sustain most married couples through the bad patches.’

Lois is reading

Sounds: ‘Guy, 18, cat lover, seeks London chick, into Sabbath. Only Freaks please.’

Paul, precociously, is reading

Watership Down: ‘Simple African villagers, who have never left their remote homes, may not be particularly surprised by their first sight of an aeroplane: it is outside their comprehension.’