The Rotters' Club (5 page)

Authors: Jonathan Coe

Miss Newman is not a good Secretary. She does not perform her duties well.

There is a lack of attention on the part of Miss Newman. At meetings of the Charity Committee, you can often see her attention wandering. I sometimes think she has other things on her mind than performing her duties as Secretary. I would prefer not to say what these other things might be.

I have made many important remarks, and addressed many observations, which have not been recorded in the minutes of the Charity Committee, due to Miss Newman. This is true of other Committee Members, but especially of me. I think she is discharging her duties with total inefficiency.

I draw this matter to your urgent attention. Brother Anderton, and personally suggest that Miss Newman be removed as Secretary of the Charity Committee forthwith. Whether or not she continues in the Design Typing Pool is of course at the firm’s discretion. But I do not think she is a good typist either.

Yours fraternally,

Victor Gibbs.

Bill wiped his brow, and yawned: an action which often signified tension with him, rather than fatigue. He didn’t need this. He could do without this busybody making life even more difficult for him, with his insinuations and his venomous innuendo. What had Miriam done, what had they both done, to inflame these suspicions? Doubtless exchanged one smile too many, held one of those gazes for just a fraction of a second too long. That was all it need take. But it was interesting that Gibbs, of all people, should have been the one to notice it.

The Charity Committee included members from all parts of the factory, who met to channel a small proportion of their respective union funds into worthy local causes, chiefly schools and hospitals, and Victor Gibbs was its treasurer. He was a clerk in the accounts department, a white-collar worker, so his wheedling use of ‘Brother Anderton’ and ‘Yours fraternally’ was little more than affectation – bordering on affront, in Bill’s view. He was from South Yorkshire; he was sour and unfriendly; but more important than any of these things, he was an embezzler. Bill was almost certain of this by now. It was the only way he could explain that mysterious cheque which the bank had returned three months ago, and which he could not remember signing. The signature had been forged: rather expertly, he had to admit. Since then Bill had been making regular visits to the bank to inspect the Committee’s cheques and he had found three more made out to the same payee: one with the chairman’s signature, and two with Miriam’s. Again, the forgeries were good, although the felony itself was hardly subtle. It made him wonder how Gibbs was expecting to get away with it. He was glad, in any case, that he had followed his instinct, which told him to say nothing at first, bide his time and wait for the evidence to mount up. This had put him in a strong position. If Gibbs was planning to make trouble about Miriam, he would not find Bill a very sympathetic listener. His malice would be turned back on him; repaid with interest.

Bill filed the letter carefully among his papers. He would not dignify it with a reply, but nor would he destroy it. It would come in useful, he was sure of that. And besides, he made it a point of principle not to destroy any documents. He was building up an archive, a record of class struggle in which every detail was important, and for which future generations of students would be grateful. He already had plans to donate it to a university library.

The music upstairs had been turned down. He could hear Irene and Doug having an argument; nothing too serious, not one of their slanging matches, just a bit of bickering and teasing. That was all right. They got on OK, those two. The family was secure, for the time being. No thanks to him, it was true…

Next on the pile were a couple of related items: a scrap of paper he had found last week, pinned to the notice board in the works canteen and a crudely printed leaflet that had lately been in circulation among his members.

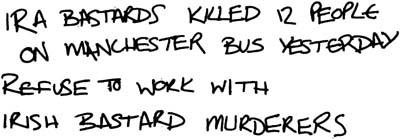

The notice said:

The leaflet was the latest effusion from something called ‘The Association of British People’, a far-right offshoot, more cranky and less organized even than the National Front. Bill found their propaganda pathetic, and would have been tempted to bin it without a second glance. But there were rumours that these people had been behind a recent attack in Moseley on two Asian teenagers, who had been found beaten half to death outside a chip shop, and he didn’t want anything like that spreading to the factory. There was plenty of scope for violence in a big workplace. All sorts of stuff could go unnoticed.

Reluctantly, then, he glanced through the opening lines.

Workers of Britain! Unite and wake up!

Your job is at risk. Your home and livelihood are at risk.

Your whole way of life is threatened as never before.

Neither Heath nor Wilson nor Thorpe has the will to stop the tide of coloured immigration into this country. All are slaves to the liberal establishment way of thinking. These people do not just tolerate the black man, they think he is actually superior to the true-born Englishman. They want to fling the gates of this country wide open to the black man, and do not give a damn for the jobs and homes of the white Englishman that will inevitably be lost as a result.

Look around you at your place of work and you will find that the number of black men in the workplace has increased tenfold. You are being told to work alongside them but note that you are being

TOLD

not

ASKED.

If this has also happened to you, you may be interested to know some of the following scientific

FACTS:

1.

The black man is not as intelligent as the white man. His brain is genetically not so well developed. Therefore, how can he do the same job of work?

2.

The black man is lazier than the white man. Ask yourselves, why the British-Empire conquered the Africans and Indians, and not the other way around? Because the white races are superior in industry and intelligence. Historical

FACT.

3.

The black man is not so clean. And yet you are being asked to share a place of work, perhaps eat in the same canteen, perhaps even use the same toilet seat. What are the implications for health and the spread of disease? More scientific research needed.

Bill did not bother to read any further. He already spent too much of his time organizing lectures and meetings to counteract this sort of nonsense, making sure the union put out its own anti-racist pamphlets, most of which he ended up having to write himself (and he was no writer). Today, taken together, the scribbled message and this putrid leaflet served to depress him profoundly. It was so easy, so stupidly easy, for the workforce to find reasons for hating each other when they should be uniting against the common enemy. For all that effort to mean nothing.

These gloomy thoughts – made darker by the clouds of conscience-stricken anxiety that his reflections upon Miriam had gathered together – were scarcely relieved by what he saw on the television a few minutes later. Irene had brought him his tea, strong and sugared, and together they went to watch

Midlands Today,

sitting side by side on the sofa, her hand resting fondly on his knee. (She persisted in these gestures, either not minding or not noticing that he never returned them.) The Longbridge strike was the third item on the programme.

‘The telly people turned up, then,’ said Irene. ‘Did they talk to you? Are you going to be on?’

‘No, they’d all gone home by the time I came out. I don’t suppose they bothered to –’

He broke off, and was suddenly swearing at the television screen, driven to fury by the spectacle of Roy Slater – yes, Slater, the bastard! – addressing some reporter with a microphone thrust before his face. How in God’s name had

he

managed to get to the cameras before anyone else today? And what gave him the right to start mouthing off about the dispute before they’d had a chance even to agree an official line?

‘They’re doing it again, the management,’ Slater was saying, in that coarse, hollow voice of his. ‘Every time they go back on their promises, they chip away at the workers’ pay packets. It’s not good enough. It’s –’

‘It’s not about pay, you fool!’ Bill was shouting, cutting across the rest of Slater’s answer. ‘This strike is not about pay!’

‘What is it about, then?’ said Doug, who had appeared in the living-room doorway, drawn by the sound of the television.

‘This ignorant… pillock!’ For a moment Bill was speechless with anger. ‘It’s about right and wrong,’ he then explained, ostensibly to his son but more, you might have thought, to an imagined audience of television viewers. ‘They’ve been docking workers’ pay because of the time they’ve been spending cleaning themselves up in the last half hour of the shift. It’s about the right to… cleanliness, and hygiene.’

‘… just as long as it takes,’ Slater was insisting, on the screen. ‘We want this money. We have a right to this money. We’re going to get –’

‘It’s not about bloody money!’

Bill shouted, a hand coursing frantically, now, through the thinning hair above his forehead. ‘You didn’t even call this strike, Slater. You know nothing about it. You don’t know what the bloody hell you’re talking about.’

‘Is he the one that was so rude to me,’ Irene ventured, ‘down at the club that time? When you were buying drinks?’

‘He’s rude to everybody. He’s a nasty piece of work. And he’s got no

right,

no right at all, to get up on the television and start –’ The telephone rang, shrill and excitable. Bill scarcely missed a beat as he went to pick it up. ‘Here we go, then. This’ll be Kevin. He’ll have seen it. He’ll be screaming blue murder.’ He grabbed the receiver and snapped: ‘Hello?’

It wasn’t Kevin. It was Miriam.

‘Hello, Bill. Is this a good time?’

He still retained, occasionally, the capacity to surprise himself: it took only a second or two to recover, and take the measure of the situation.

‘Oh, hello, Kev. Yes, I saw it. What’s… what’s your view, then? How do you think we should proceed?’

Miriam, too, was accustomed to this kind of subterfuge. ‘Listen, Bill, I was ringing about tomorrow night. I wondered if you might be free.’

‘Always…’ – he glanced at his wife, whose attention was concentrated on the television – ‘always difficult, that, isn’t it? Always a bit of a problem.’

‘But Bill –

darling

–’ (was the word calculated, or had it come naturally? She would surely know the effect it would have on him) ‘– it’s Valentine’s Day.’

‘Yes, I’m aware of that. Well aware. But –’

‘And I’ve got the house to myself. All evening.’

Bill was silenced, for a moment.

‘Claire’s going to some disco, you see. And it’s parent-teachers. Parent-teachers night at King William’s. Mum and Dad’ll be out.’

And so will I, you fool,

Bill said to himself.

Had you not thought of that? I’ve got to be there too.

And yet, at the same time, a heavenly vista opened up to him. An hour alone with Miriam; maybe two. Privacy.

A bed.

They had never made love in a bed. Every time so far had been rushed, fumbled, in some corner of the factory, always the threat of someone disturbing them, never the chance to do it properly, to take their time, to undress. And this way they could undress. He could see her naked. For a whole hour; maybe two.

But it was parent-teachers night. Irene would expect him to go. She had a right to expect that. And he owed it to Doug.

‘Can you not find an alternative, Kev?’ he said loudly into the phone. ‘I have to say that of all the nights you could have chosen, that has to be the worst.’

‘Please try to make it, Bill.

Please.

Just think what it would be like…’

‘Yes, all right, all right.’ He cut her off, not wanting to listen to her pleading. The picture was quite vivid enough as it was. He sighed heavily. ‘Well, if that’s when it has to be, then… that’s when it has to be.’ He could hear her relief at the other end of the line. An emotion swelled inside him: pride, or gratification. A tender feeling; there was almost something paternal in it. ‘So what time are you calling the meeting?’

‘Seven-thirty? Can you make it by then?’

A final sigh: thick with weariness and resignation. ‘OK, Kev. I’ll be there. We’ll sort this thing out once and for all. But after this, you owe me one – OK? I mean it.’

‘’Bye, Billy,’ said Miriam, using an endearment he would never have tolerated from Irene.

‘Ta-ra then,’ said Bill, and replaced the receiver.

They had tea together, the three of them, sausage, beans and chips, and it wasn’t until Doug had gone back upstairs to do his homework and listen to the new record again that Irene broached the subject.