The Roughest Riders (28 page)

Read The Roughest Riders Online

Authors: Jerome Tuccille

There was little question, though, that the vast majority of opinions among black Americans tilted against what was increasingly viewed as an imperialistic adventure. Many Buffalo Soldiers heading off to do battle again for white America openly expressed their views. Private William Fulbright adamantly stated that the war was “a gigantic scheme of robbery and oppression.” Robert L. Campbell, another black trooper, told the press that “these people are right

and we are wrong, terribly wrong.” No man “who has any humanity about him at all would desire to fight against such a cause as this,” he added. Booker T. Washington said, “Until our nation has settled the Indian and Negro problems, I do not think we have a right to assume more social problems.” E. E. Cooper, another leading black intellectual of the period, warned that it was “impossible to Christianize and civilize people at gunpoint.” And the black dissenters were not alone; many influential whites, including Mark Twain, were increasingly alarmed by McKinley's imperialistic foreign policy. “We can have our usual flag,” the great satirist wrote, “with the white stripes painted black and the stars replaced by the skull and crossbones.”

T

he Buffalo Soldiers who set foot on the soil of the Philippines were greeted by posters and leaflets addressed to “The Colored American Soldier” and describing the lynching, discrimination, and abuse black people had suffered in the United States. The rebels asked them if they really wanted to be the instruments of white imperialist ambitions to oppress other people of color. If they were willing to switch sides, not only would Aquino and his followers welcome them with open arms, they would reward the black Americans with positions of responsibility and power.

For the most part, the Buffalo Soldiers resisted the attempt to sap their fighting spirit and turn against their compatriots, even as they understood the logic behind Aquino's message. On October 7, 1899, the men of the Twenty-Fourth exhibited great valor as they waded through waist-deep mud in an attempt to assault rebel outposts in San Agustin, north of Manila, on the periphery of Aquino's base of operations. The thrust was successful. Both sides exchanged a few rounds of gunfire, and the insurrectos fell back to the north, where they had more support from their fellow revolutionaries.

The Twenty-Fourth moved northward in pursuit of the rebels and engaged them a few days later in the mountain village of Arayat, where they overran enemy trenches and sent them fleeing, with the Twenty-Fourth suffering only a single casualty in the operation. The troops were rolling ahead in harsh terrain, so far encountering only minor opposition as the other black units circled in on the mountainous region toward the heart of Aquino's stronghold. Under the command of Captain Joseph B. Batchelor, a force of 350 Buffalo Soldiers entered an area of the islands where few non-Filipinos had ever ventured. They continued to close in on the enemy through the final weeks of October and into November and December. The early victories came easy, with the insurrectos pulling back and regrouping on more familiar turf as the Americans attempted to close in on Aquino and his followers. Then, suddenly, the momentum of the war suffered an unexpected reversal, and the road to American victory seemed loaded with pitfalls.

The insurrectos changed tactics and adopted a guerrilla style of fighting more suitable to their mountain redoubt. It was an unconventional kind of warfare, one that Americans had not faced before, and it proved highly effective for the inhabitants of the mountains, who were familiar with every square inch of their land. In addition, Aquino's message exhorting the Americans to join his fight for independence instead of advancing the cause of US imperialism began to take root in the minds of both some white troops as well as a handful of Buffalo Soldiers. During the course of the war, sixteen Americans would defect to Aquino, six of them Buffalo Soldiers. The most famous among them, and the one most valuable to the cause of Filipino independence, was Corporal David Fagen of the Twenty-Fourth, who switched sides on November 17, just as his brothers were scoring their early victories in San Agustin and Arayat.

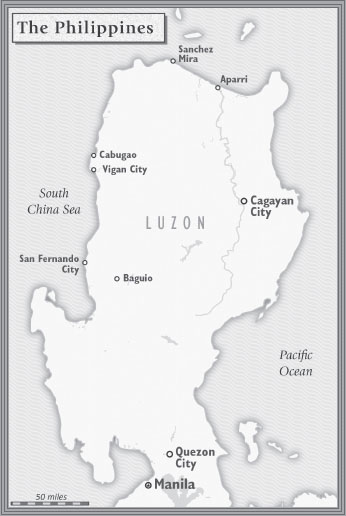

Ground hostilities in the Philippines commenced when a band of

insurrectos

led by Emilio Aguinaldo attacked US troops stationed on the island in February 1899.

Based on a map produced by

www.Google.com/maps/place/Philippines

.

While most of the Buffalo Soldiers remained loyal, Fagen had his sympathizers among the ranks. “We're only regulars and black ones at that,” one soldier wrote home. “I expect that when the Philippine question is settled they'll detail us to garrison the islands. Most of us will find our graves there.” Sergeant Major John W. Galloway of the Twenty-Fourth was even more adamant about the bind

that ensnared the black troops. “The whites have begun to establish their diabolical race hatred in all its home rancor in Manila,” he wrote in a letter. He maintained that white Americans were determined to intimidate both Spaniards and Filipinos right from the start in order to impose white supremacy in the colony after the war was over.

Fagen had enlisted in the army in Tampa in June 1898 and was honorably discharged the following January. He was considered a model infantryman by his white officers, who had high praise for his combat performance in Cuba. They rewarded his efforts by promoting him to corporal in short order. Fagen reenlisted in June 1899 and sailed with the Twenty-Fourth from San Francisco to the Philippines. He fought against the Filipinos mostly around Arayat, until he decided he was on the wrong side of the conflict. Swayed by Aquino's appeals to black Americans to join his revolution, Fagen arranged to be conducted over to the insurgents' side on horseback by one of Aquino's men, who slipped away with him into the jungle. Fagen rose through the ranks of the rebel army during the next year and a half, being promoted first to lieutenant, then to captain, and finally leading a band of rebels who called him General Fagen.

His exploits in Luzon earned him a front-page story in the

New York Times

, which reported that he was a “cunning and highly skilled guerrilla officer who harassed and evaded large conventional American units.” The article maintained that Fagen had been particularly brutal toward his former comrades, routinely murdering those who were taken prisoner. But two members of the Twenty-Fourthâblack trooper George Jackson and white lieutenant Frederick Alstaetterâsaid that Fagen treated both of them humanely after he captured them, although Alstaetter claimed that Fagen did steal his West Point ring. Other soldiers with the Twenty-Fourth insisted that Fagen had only reluctantly switched sides after having endured several racially motivated altercations with some white officers.

His legend in the region as a formidable supporter of Aquino grew to the point where a US commander, General Frederick Funston, placed a $600 bounty on his head, stating that Fagen was “entitled to the same treatment as a mad dog.” A Tagalog hunter named Anastacio Bartolome delivered a decomposed head and a West Point ring to Funston on December 5, 1901, saying that he and other hunters had killed Fagen while he was bathing in a river. But the rebels insisted that Fagen was still alive and well, living in the mountains; the hunter had brought in someone else's head, they said, to collect the bounty money. The rest of Fagen's body couldn't be found where Bartolome said he had buried it alongside the river, so the evidence was deemed inconclusive, with a head and a ring on one side of the argument and a missing body supporting the other. In any event, the Americans were content to put an end to the mythology surrounding Fagen's exploits in the mountains of Luzon.

“Fagen was a traitor and died a traitor's death,” read an editorial in the black

Indianapolis Freeman

the same month the hunter delivered the unrecognizable, decomposed head, “but he was a man no doubt prompted by honest motives to help a weaker side, and one with which he felt allied by ties that bind.”

Notwithstanding Fagen's betrayal and the ambivalence many Buffalo Soldiers experienced as they climbed over the mountains and slogged through the jungles of Luzon, the great majority of them fought loyally with their white compatriots as the war to suppress the insurrectos wore on longer than anyone anticipated. On November 23, 1899, less than a week after Fagen's defection, the Twenty-Fourth marched forty-five miles from Cabanatuan City north of Manila to Tayug and reported to General Kent, who had

led the unit in Cuba. The plan called for the men to cross over the mountain range to the east, down into the valley floor marked by the Cagayan River, to head off Aquino's men before they could reach the strategically important area. It was a treacherous stretch of real estate over poorly mapped mountains that required several days of hazardous trekking, with every available horse roped into service for a pack train.

The troops ground their way over steep cliffs, “hardly any of them surmountable except by zigzag paths cut on shelves from a foot to eighteen inches wide,” Lawton wrote in his report of the campaign. Private Bruce Williams with the Twenty-Fourth said that the men ate “so much rice that we are ashamed to look at it. I, for one, am sick of it.” For a while, their diet consisted of nothing but rice and bitter green coffee, with little or no potable water to drink. They also ate sweet potatoes given to them by friendly natives, Williams added, although they tasted as though they were “cooked by barbarians.”

As they wound their way down into the valley, they learned that Aquino was approaching with a force of his own from the north. Lawton directed Captain Batchelor to take the 350 black troops in his command and block Aquino's path by following the river all the way to the coast on the northern rim of Luzon. By commanding the valley floor from south to north across the region, Lawton and Batchelor would protect their men from being enveloped by the insurrectos. They skirmished with the enemy along the way, but most of the encounters were brief hit-and-run attacks, with little damage inflicted on either side as Aquino's guerrillas disappeared back into the dense jungle. The biggest hurdle for the Twenty-Fourth was the high, sharp-bladed grass that sliced through their trousers like bayonets and cut their legs, ankles, and hands when the men tried to brush it away.

Batchelor pushed his men onward toward the coast. They marched along the banks of the river toward Naguilian, where

the Cagayan intersected a smaller stream called the Magat River. When they approached the confluence of the two waterways, the Buffalo Soldiers could see a band of several hundred rebels staring down at them from a cliff overlooking the far bank. They exchanged fire with the insurrectos, with neither side prevailing because of the distance. The Americans had little choice but to ford the stream to reach the other side, but the water ran deep and the current was swift. The men searched the area and were unable to find any suitable materials to build a viable raft, so they tore down a hut at the edge of the jungle and began to cobble together a workable model.

As they were laboring away on it, four Buffalo Soldiers and one of their officers attempted to swim across the river, but one of the enlisted men, Corporal John H. Johnson, drowned in the effort. The four survivors made it across and found enough wood along the shore to construct a raft of their own. Amazingly, they pulled off the feat without being riddled by insurrecto bullets. They completed the job and floated back over to get their guns and help the other men complete the raft they were building. Finally, nine of them set off across the Magat on their makeshift rafts of wooden planks and bamboo poles tethered together with vines, canteen straps, and shelter-halves torn into strips. To the surprise of their comrades who stood on the shore cheering them on, the troops made it safely across and drove the insurrectos off into the brush. No one was more astonished by their success than their commander, Captain Batchelor.

“To see nine men,” he later reported to Lawton, “the officers in their drawers and the privates naked, cross such a stream by such means, and drive an entrenched force not less than ten times their number, in broad daylight where their number must soon become known, is something not soon to be forgotten.”